J Bacteriol Virol.

2009 Mar;39(1):11-19. 10.4167/jbv.2009.39.1.11.

Isolation and Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria Inhibiting the Proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea. joh@chonnam.ac.kr

- KMID: 1474176

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2009.39.1.11

Abstract

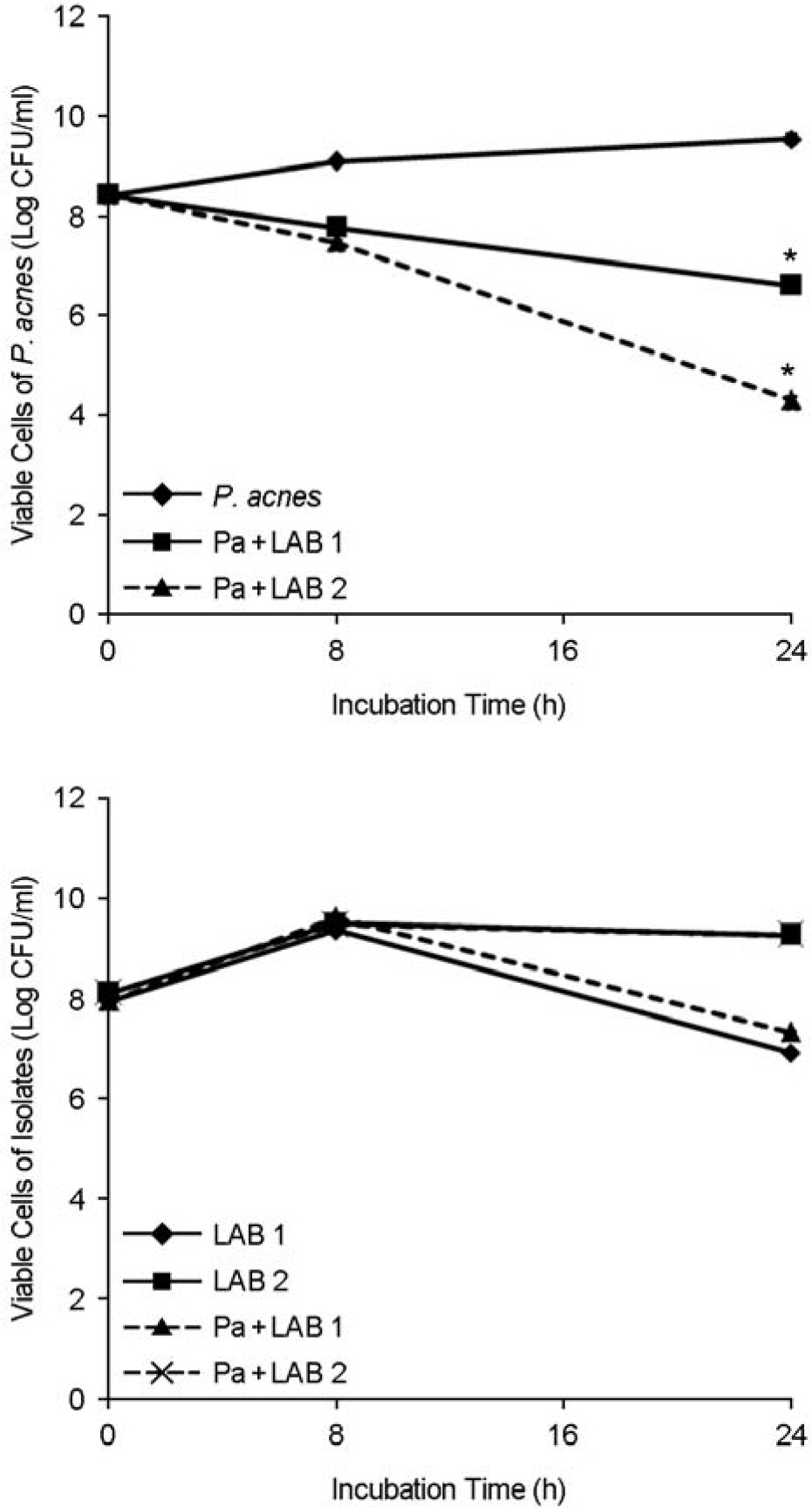

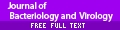

- Propionibacterium acnes is the most common causative agent of acne. Staphylococcus epidermidis is another major bacterial strain to be found in acne lesions. Two strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were isolated from normal inhabitants of humans, which inhibited the proliferation of P. acnes and S. epidermidis. The growth of P. acnes and S. epidermidis was decreased by 4-log scales after incubation for 24 h with LAB isolates, whereas the growth rate of selected LAB isolates were not affected by these pathogenic bacteria. This antibacterial activity of LAB isolates was related to lactic acids, hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocin-like compound production. Two LAB isolates efficiently adhered to human keratinocytes HaCaT and were identified by API 50 CHL medium kit and 16S rDNA partial sequencing analysis. The similarity of 16S rDNA sequences between one isolate and Lactobacillus salivarius subsp. salicinius was 100%, which suggests that they were L. salivarius subsp. salicinius. On the other hand, 16S rDNA sequence similarity between the other isolate and Lactobacillus fermentum was 99.04%, which indicates that it was L. fermentum. In conclusion, these results demonstrate that the two LAB strains isolated from human body were identified as L. salivarius subsp. salicinius and L. fermentum, which inhibit the proliferation of P. acnes and S. epidermidis.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Acne Vulgaris

Bacteria

DNA, Ribosomal

Hand

Human Body

Humans

Hydrogen Peroxide

Keratinocytes

Lactic Acid

Lactobacillus

Lactobacillus fermentum

Propionibacterium

Propionibacterium acnes

Pyridines

Sprains and Strains

Staphylococcus

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Thiazoles

Weights and Measures

DNA, Ribosomal

Hydrogen Peroxide

Lactic Acid

Pyridines

Thiazoles

Figure

Reference

-

1). Harper JC. An update on the pathogenesis and management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004. 51:S36–8.

Article2). Thiboutot DM. Acne. An overview of clinical research findings. Dermatol Clin. 1997. 15:97–109.3). Nishijima S., Kurokawa I., Katoh N., Watanabe K. The bacteriology of acne vulgaris and antimicrobial susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated from acne lesions. J Dermatol. 2000. 27:318–23.4). Jeremy AH., Holland DB., Roberts SG., Thomson KF., Cunliffe WJ. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003. 121:20–7.

Article5). Hughes BR., Murphy CE., Barnett J., Cunliffe WJ. Strategy of acne therapy with long-term antibiotics. Br J Dermatol. 1989. 121:623–8.

Article6). Breathnach AS., Nazzaro-Porro M., Passi S. Azelaic acid. Br J Dermatol. 1984. 111:115–20.

Article7). Akhavan A., Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003. 4:473–92.8). Eady EA., Cove JH., Holland KT., Cunliffe WJ. Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: association with therapeutic failure. Br J Dermatol. 1989. 121:51–7.

Article9). Wawruch M., Bozekova L., Krcmery S., Kriska M. Risks of antibiotic treatment. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2002. 103:270–5.10). Nam C., Kim S., Sim Y., Chang I. Anti-acne effects of oriental herb extracts: a novel screening method to select anti-acne agents. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2003. 16:84–90.

Article11). Tan HH. Antibacterial therapy for acne: a guide to selection and use of systemic agents. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003. 4:307–14.12). Ahrné S., Nobaek S., Jeppsson B., Adlerberth I., Wold AE., Molin G. The normal Lactobacillus flora of healthy human rectal and oral mucosa. J Appl Microbiol. 1998. 85:88–94.13). Redondo-López V., Cook RL., Sobel JD. Emerging role of lactobacilli in the control and maintenance of the vaginal bacterial microflora. Rev Infect Dis. 1990. 12:856–72.14). Choi HJ., Cheigh CI., Kim SB., Lee JC., Lee DW., Choi SW., Park JM., Pyun YR. Weissella kimchi sp. nov., a novel lactic acid bacterium from kimchi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002. 52:507–11.15). Martini MC., Lerebours EC., Lin WJ., Harlander SK., Berrada NM., Antoine JM., Savaiano DA. Strains and species of lactic acid bacteria in fermented milks (yogurts): effect on in vivo lactose digestion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991. 54:1041–6.16). Elmer GW. Probiotics: “living drugs”. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001. 58:1101–9.

Article17). Gorbach SL. Lactic acid bacteria and human health. Ann Med. 1990. 22:37–41.

Article18). Kaewsrichan J., Peeyananjarassri K., Kongprasertkit J. Selection and identification of anaerobic lactobacilli producing inhibitory compounds against vaginal pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006. 48:75–83.

Article19). Mastromarino P., Brigidi P., Macchia S., Maggi L., Pirovano F., Trinchieri V., Conte U., Matteeuzzi D. Characterization and selection of vaginal Lactobacillus strains for the preparation of vaginal tablets. J Appl Microbiol. 2002. 93:884–93.20). Eschenbach DA., Davick PR., Williams BL., Klebanoff SJ., Young-Smith K., Critchlow CM., Holmes KK. Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989. 27:251–6.21). Scaletsky IC., Silva ML., Trabulsi LR. Distinctive patterns of adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1984. 45:534–6.22). Rochelle PA., Fry JC., Parkes RJ., Weightman AJ. DNA extraction for 16S rRNA gene analysis to determine genetic diversity in deep sediment communities. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992. 79:59–65.

Article23). Weisburg WG., Barns SM., Pelletier DA., Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991. 173:697–703.

Article24). Chen Q., Koga T., Uchi H., Hara H., Terao H., Moroi Y., Urabe K., Furue M. Propionibacterium acnes-induced IL-8 production may be mediated by NF-kappaB activation in human monocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2002. 29:97–103.25). Lee WL., Shalita AR., Suntharalingam K., Fikrig SM. Neutrophil chemotaxis by Propionibacterium acnes lipase and its inhibition. Infect Immun. 1982. 35:71–8.26). Graham GM., Farrar MD., Cruse-sawyer JE., Holland KT., Ingham E. Proinflammarory cytokine production by human keratinocytes stimulated with Propionibacterium acnes and P. acnes GroEL. Br J Dermatol. 2004. 150:421–8.27). Schaller M., Loewenstein M., Borelli C., Jacob K., Vogeser M., Burgdorf WH., Plewig G. Induction of a chemoattractive proinflammatory cytokine response after stimulation of keratinocytes with Propionibacterium acnes and coproporphyrin III. Br J Dermatol. 2005. 153:66–71.28). Kim SS., Kim JY., Lee NH., Hyun CG. Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects of Jeju medicinal plants against acneinducing bacteria. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2008. 54:101–6.

Article29). Wang JP., Ho TF., Chang LC., Chen CC. Anti-inflammatory effect of magnolol, isolated from Magnolia officinalis, on A23187-induced pleurisy in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1995. 47:857–60.30). Ho KY., Tsai CC., Chen CP., Huang JS., Lin CC. Antimicrobial activity of honokiol and magnolol isolated from Magnolia officinalis. Phytother Res. 2001. 15:139–41.31). Arihara K., Ogihara S., Mukai T., Itoh M., Kondo Y. Salivacin 140, a novel bacteriocin from Lactobacillus salivarius subsp. salicinius T140 active against pathogenic bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996. 22:420–4.32). Smith SI., Aweh AJ., Coker AO., Savage KO., Abosede DA., Oyedeji KS. Lactobacilli in human dental caries and saliva. Microbios. 2001. 105:77–85.33). Ocaña VS., Pesce de Ruiz Holgado AA., Nader- Macías ME. Selection of vaginal H2O2-generating Lactobacillus species for probiotic use. Curr Microbiol. 1999. 38:279–84.34). Leke N., Grenier D., Goldner M., Mayrand D. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on growth and selected properties of Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999. 174:347–53.35). Ohwada T., Shirakawa Y., Kusumoto M., Masuda H., Sato T. Susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide and catalase activity of root nodule bacteria. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999. 63:457–62.

Article36). Grimont F., Grimont PA. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid gene restriction patterns as potential taxonomic tools. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1986. 137B:165–75.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Microorganisms Isolated from Acne and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility

- Analysis and Clinical Correlation of Bacteria Cultured from Patients with Inflammatory Acne

- A study on the chemotactic activity of the peripheral blood neutrop- hils in acne patients to the cytosol antigen of propionibacterium acnes

- Antimicrobial Effects of Oleanolic Acid, Ursolic Acid, and Sophoraflavanone G against Enterococcus faecalis and Propionibacterium acnes

- Production and Characterization of Antibodies to Propionibacterium acnes from Immunized Chicken Eggs