Investig Clin Urol.

2019 Mar;60(2):75-83. 10.4111/icu.2019.60.2.75.

Microbiome diversity in carriers of fluoroquinolone resistant Escherichia coli

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine, San Antonio, TX, USA. liss@uthscsa.edu

- 2South Texas Veterans Healthcare System, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 3Department of Cell Systems and Anatomy, UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 4Genome Sequencing Facility (GSF) in the Greehey Children's Cancer Research Institute (Greehey CCRI), San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 5Resphera Biosciences, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 6Department of Medicine, UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- KMID: 2438817

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2019.60.2.75

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQR) Escherichia coli causes transrectal prostate biopsy infections. In order to reduce colonization of these bacteria in carriers, we would like to understand the surrounding microbiome to determine targets for decolonization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

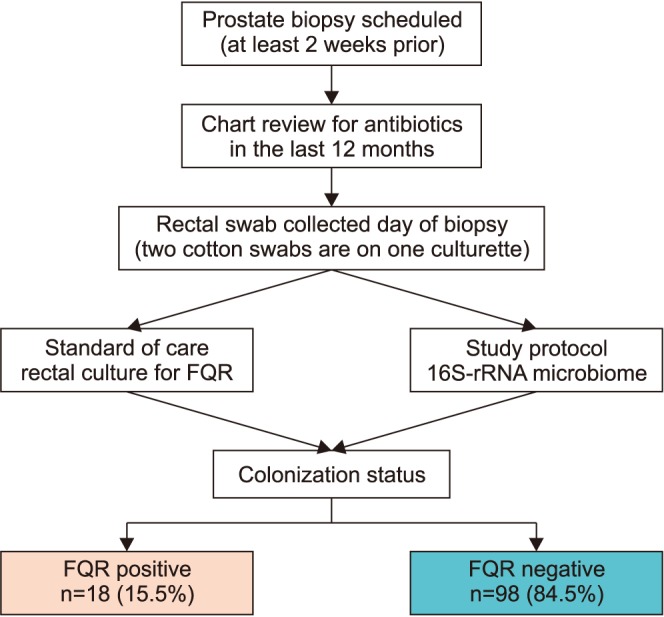

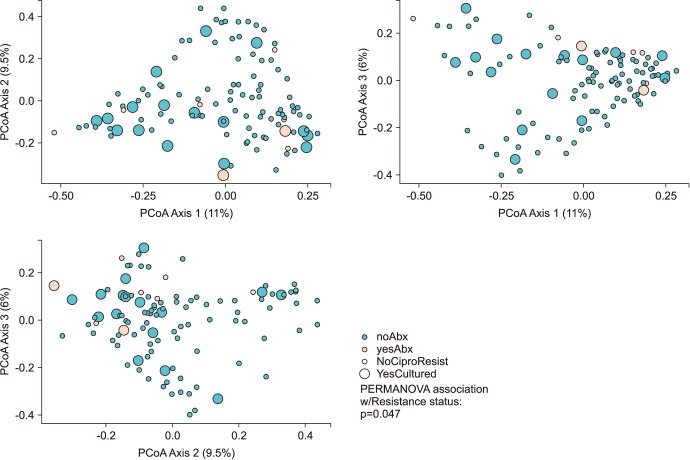

We perform an observational study to investigate the microbiome differences in men with and without FQR organisms found on rectal culture. A rectal swab with two culturettes was performed on men before an upcoming prostate biopsy procedure as standard of care to perform "targeted prophylaxis." Detection of FQR was performed by the standard microbiology lab inoculates the swab onto MacConkey agar containing ciprofloxacin. The extra swab was sent for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (MiSeq paired-end) using the V1V2 primer. Alpha and beta-diversity analysis were performed using QIIME. We used PERMANOVA to evaluate the statistical significance of beta-diversity distances within and between groups of interest.

RESULTS

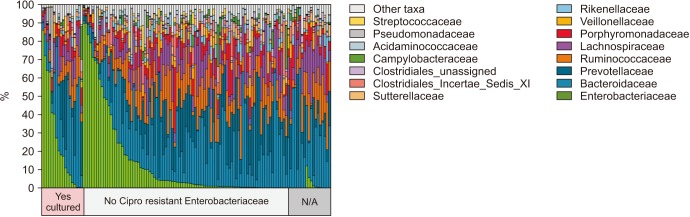

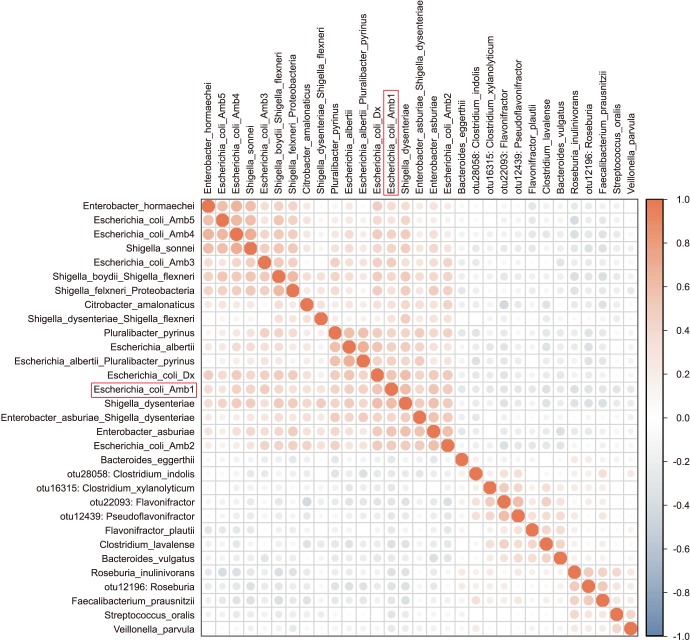

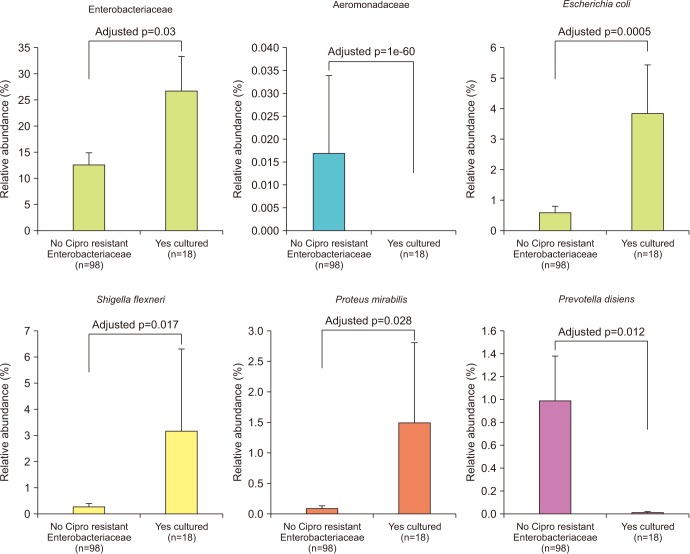

We collected 116 rectal swab samples before biopsy for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. We identified 18 isolates (15.5%, 18/116) that were positive and had relative reduced diversity profiles (p < 0.05). Enterobacteriaceae were significantly over-represented in the FQR subjects (adjusted p=0.03).

CONCLUSIONS

Microbiome analysis determined that men colonized with FQR bacteria have less diverse bacterial communities (dysbiosis), higher levels of Enterobacteriaceae and reduced levels of Prevotella disiens. These results may have implications in pre/probiotic intervention studies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, Ricker W, Schaeffer EM. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011; 186:1830–1834. PMID: 21944136.

Article2. Williamson DA, Barrett LK, Rogers BA, Freeman JT, Hadway P, Paterson DL. Infectious complications following transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy: new challenges in the era of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2013; 57:267–274. PMID: 23532481.

Article3. Roberts MJ, Williamson DA, Hadway P, Doi SA, Gardiner RA, Paterson DL. Baseline prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and subsequent infection following prostate biopsy using empirical or altered prophylaxis: a bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014; 43:301–309. PMID: 24630305.

Article4. Taylor AK, Zembower TR, Nadler RB, Scheetz MH, Cashy JP, Bowen D, et al. Targeted antimicrobial prophylaxis using rectal swab cultures in men undergoing transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy is associated with reduced incidence of postoperative infectious complications and cost of care. J Urol. 2012; 187:1275–1279. PMID: 22341272.

Article5. Budding AE, Grasman ME, Eck A, Bogaards JA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Rectal swabs for analysis of the intestinal microbiota. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e101344. PMID: 25020051.

Article6. CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twentieth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2010.7. Gevers D, Knight R, Petrosino JF, Huang K, McGuire AL, Birren BW, et al. The Human Microbiome Project: a community resource for the healthy human microbiome. PLoS Biol. 2012; 10:e1001377. PMID: 22904687.

Article8. Human Microbiome Project Consortium. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012; 486:215–221. PMID: 22699610.9. Jumpstart Consortium Human Microbiome Project Data Generation Working Group. Evaluation of 16S rDNA-based community profiling for human microbiome research. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e39315. PMID: 22720093.10. Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012; 486:207–214. PMID: 22699609.11. Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:2957–2963. PMID: 21903629.

Article12. Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:266–267. PMID: 19914921.

Article13. McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012; 6:610–618. PMID: 22134646.

Article14. Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001; 125:279–284. PMID: 11682119.

Article15. Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Savelkoul PH, Wolffs PF. The human microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Front Microbiol. 2013; 4:87. PMID: 23616784.

Article16. Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010; 464:59–65. PMID: 20203603.

Article17. Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011; 473:174–180. PMID: 21508958.

Article18. Ghosh TS, Gupta SS, Nair GB, Mande SS. In silico analysis of antibiotic resistance genes in the gut microflora of individuals from diverse geographies and age-groups. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e83823. PMID: 24391833.

Article19. Liss MA, Johnson JR, Porter SB, Johnston B, Clabots C, Gillis K, et al. Clinical and microbiological determinants of infection after transrectal prostate biopsy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:979–987. PMID: 25516194.

Article20. Spaulding CN, Klein RD, Ruer S, Kau AL, Schreiber HL, Cusumano ZT, et al. Selective depletion of uropathogenic E. coli from the gut by a FimH antagonist. Nature. 2017; 546:528–532. PMID: 28614296.

Article21. Connell I, Agace W, Klemm P, Schembri M, Mărild S, Svanborg C. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996; 93:9827–9832. PMID: 8790416.

Article22. Jones CH, Pinkner JS, Roth R, Heuser J, Nicholes AV, Abraham SN, et al. FimH adhesin of type 1 pili is assembled into a fibrillar tip structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92:2081–2085. PMID: 7892228.

Article23. Sokurenko EV, Chesnokova V, Dykhuizen DE, Ofek I, Wu XR, Krogfelt KA, et al. Pathogenic adaptation of Escherichia coli by natural variation of the FimH adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95:8922–8926. PMID: 9671780.

Article24. Liss MA, Taylor SA, Batura D, Steensels D, Chayakulkeeree M, Soenens C, et al. Fluoroquinolone resistant rectal colonization predicts risk of infectious complications after transrectal prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2014; 192:1673–1678. PMID: 24928266.

Article25. Ericsson AC, Franklin CL. Manipulating the gut microbiota: methods and challenges. ILAR J. 2015; 56:205–217. PMID: 26323630.26. Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013; 19:576–585. PMID: 23563705.

Article27. Stremmel W, Schmidt KV, Schuhmann V, Kratzer F, Garbade SF, Langhans CD, et al. Blood trimethylamine-N-oxide originates from microbiota mediated breakdown of phosphatidylcholine and absorption from small intestine. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0170742. PMID: 28129384.

Article28. Hoyles L, Jiménez-Pranteda ML, Chilloux J, Brial F, Myridakis A, Aranias T, et al. Metabolic retroconversion of trimethylamine N-oxide and the gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2018; 6:73. PMID: 29678198.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Genotypic characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from edible offal

- Risk Factors for Ciprofloxacin-Resistant Escherichia coli Strains in Pediatric Patients with Acute Urinary Tract Infection

- Escherichia coli O157: H7 Infection

- “Targeted†prophylaxis: Impact of rectal swab culture-directed prophylaxis on infectious complications after transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy

- Molecular analysis of fluoroquinolone-resistance in Escherichia coli on the aspect of gyrase and multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) genes