Korean Circ J.

2022 Apr;52(4):304-319. 10.4070/kcj.2021.0293.

Prasugrel-based De-Escalation of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With STEMI

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cardiovascular Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea

- 4Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital, Bucheon, Korea

- 5Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 6Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Suwon, Korea

- 7Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju, Korea

- 8Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan, Korea

- 9Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- 10Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 11Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea

- 12Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu, Korea

- 13Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- 14Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2528025

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2021.0293

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

De-escalation of dual-antiplatelet therapy through dose reduction of prasugrel improved net adverse clinical events (NACEs) after acute coronary syndrome (ACS), mainly through the reduction of bleeding without an increase in ischemic outcomes. Whether the benefits of de-escalation are sustained in highly thrombotic conditions such as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is unknown. We aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of de-escalation therapy in patients with STEMI or non-STsegment elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

Methods

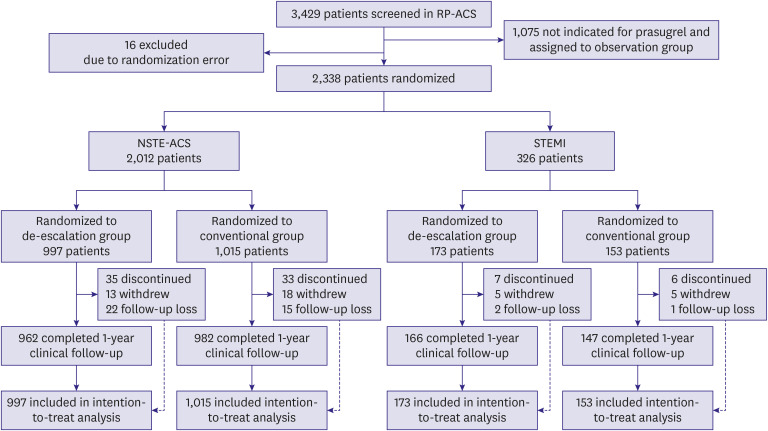

This is a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial. ACS patients were randomized to prasugrel de-escalation (5 mg daily) or conventional dose (10 mg daily) at 1-month post-percutaneous coronary intervention. The primary endpoint was a NACE, defined as a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, clinically driven revascularization, stroke, and bleeding events of grade ≥2 Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria at 1 year.

Results

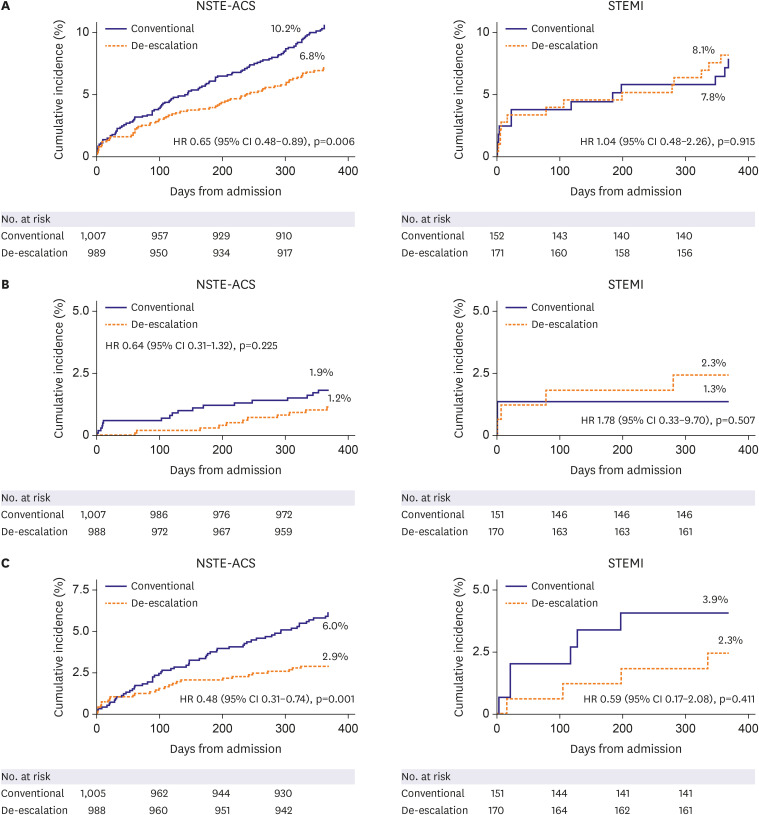

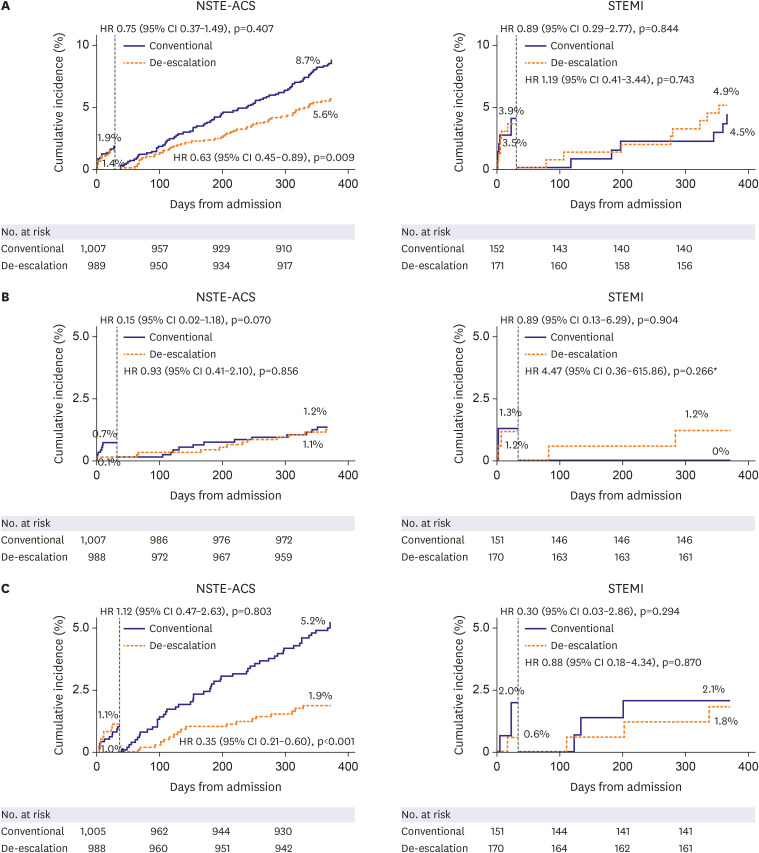

Among 2,338 patients included in the randomization, 326 patients were diagnosed with STEMI. In patients with NSTE-ACS, the risk of the primary endpoint was significantly reduced with de-escalation (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48– 0.89; p=0.006 for de-escalation vs. conventional), mainly driven by a reduced bleeding. However, in those with STEMI, there was no difference in the occurrence of the primary outcome (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.48–2.26; p=0.915; p for interaction=0.271).

Conclusions

Prasugrel dose de-escalation reduced the rate of NACE and bleeding, without increasing the rate of ischemic events in NSTE-ACS patients but not in STEMI patients.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Unguided De-Escalation Strategy From Potent P2Y12 Inhibitors in Patients Presented With ACS: When, Whom and How?

Jin Sup Park, Young-Hoon Jeong

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(4):320-323. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0022.

Reference

-

1. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:87–165. PMID: 30165437.2. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1045–1057. PMID: 19717846.

Article3. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2001–2015. PMID: 17982182.

Article4. Kang J, Park KW, Ki YJ, et al. Development and validation of an ischemic and bleeding risk evaluation tool in East Asian patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. Thromb Haemost. 2019; 119:1182–1193. PMID: 31079414.

Article5. Kang J, Park KW, Palmerini T, et al. Racial differences in ischaemia/bleeding risk trade-off during anti-platelet therapy: individual patient level landmark meta-analysis from seven RCTs. Thromb Haemost. 2019; 119:149–162. PMID: 30597509.

Article6. Ki YJ, Kang J, Park J, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term and short-term dual antiplatelet therapy: a meta-analysis of comparison between Asians and non-Asians. J Clin Med. 2020; 9:652.

Article7. Valgimigli M, Costa F, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Trade-off of myocardial infarction vs. bleeding types on mortality after acute coronary syndrome: lessons from the Thrombin Receptor Antagonist for Clinical Event Reduction in Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRACER) randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:804–810. PMID: 28363222.

Article8. Costa F, van Klaveren D, James S, et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet. 2017; 389:1025–1034. PMID: 28290994.

Article9. Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): an open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet. 2020; 396:1079–1089. PMID: 32882163.

Article10. Franchi F, Rollini F, Angiolillo DJ. Antithrombotic therapy for patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017; 14:361–379. PMID: 28230176.

Article11. Lee JM, Jung JH, Park KW, et al. Harmonizing Optimal Strategy for Treatment of coronary artery diseases--comparison of REDUCtion of prasugrEl dose or POLYmer TECHnology in ACS patients (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS RCT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015; 16:409. PMID: 26374625.12. Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. Durable polymer versus biodegradable polymer drug-eluting stents after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial. Circulation. 2021; 143:1081–1091. PMID: 33205662.

Article13. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Circulation. 2018; 137:2635–2650. PMID: 29891620.

Article14. Montalescot G, Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, et al. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 373:723–731. PMID: 19249633.

Article15. Steg PG, James S, Harrington RA, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes intended for reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial subgroup analysis. Circulation. 2010; 122:2131–2141. PMID: 21060072.

Article16. Udell JA, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Montalescot G, Wiviott SD. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction according to timing of percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 subgroup analysis (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7:604–612. PMID: 24947719.

Article17. Velders MA, Abtan J, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2016; 102:617–625. PMID: 26848185.

Article18. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Cho YH, et al. Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the TICO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020; 323:2407–2416. PMID: 32543684.

Article19. Lee SJ, Cho JY, Kim BK, et al. Ticagrelor monotherapy versus ticagrelor with aspirin in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021; 14:431–440. PMID: 33602439.

Article20. Kupka D, Sibbing D. De-escalation of P2Y12 receptor inhibitor therapy after acute coronary syndromes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:863–872. PMID: 30238704.

Article21. Lee HS, Park KW, Kang J, Han JK, Kim HS. De-escalation of prasugrel results in higher percentage of patients within optimal range of platelet reactivity. Thromb Haemost. 2021; [Epub ahead of print].22. Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:2032–2042. PMID: 31556978.

Article23. Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. 6-month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018; 391:1274–1284. PMID: 29544699.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- De-Escalation of P2Yâ‚â‚‚ Receptor Inhibitor Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- De-escalation strategies of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome

- Randomized Comparison of the Platelet Inhibitory Efficacy between Low Dose Prasugrel and Standard Dose Clopidogrel in Patients Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Simultaneous Multivessel Acute Stent Thrombosis in a Patient with Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Dual antiplatelet therapy and non-cardiac surgery: evolving issues and anesthetic implications