Investig Clin Urol.

2019 Nov;60(6):454-462. 10.4111/icu.2019.60.6.454.

The clinical utility of transperineal template-guided saturation prostate biopsy for risk stratification after transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Ewha Womans University Medical Center, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Urology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hwanggyun.jeon@samsung.com

- KMID: 2461057

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2019.60.6.454

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the clinical utility of transperineal template-guided saturation prostate biopsy (TPB) for risk stratification after transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy.

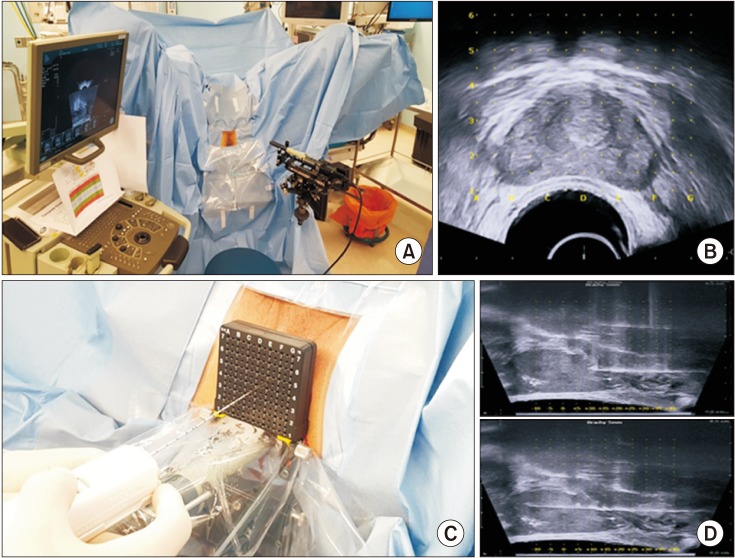

MATERIALS AND METHODS

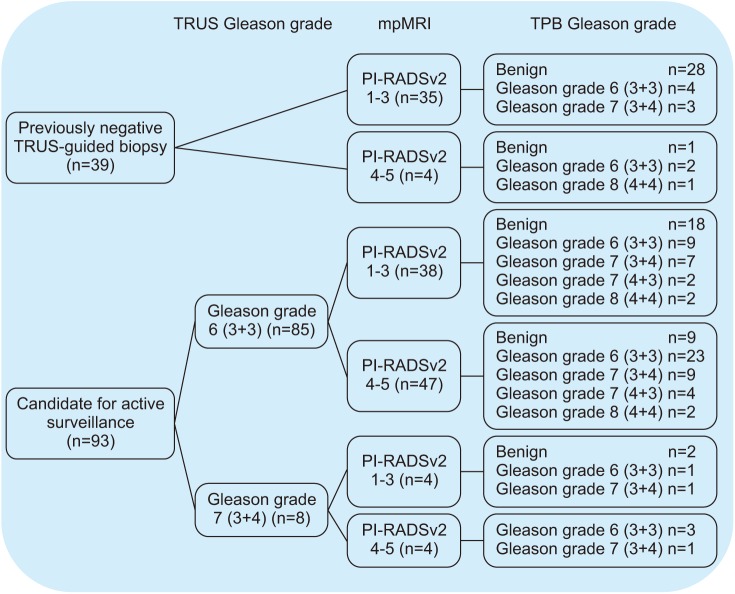

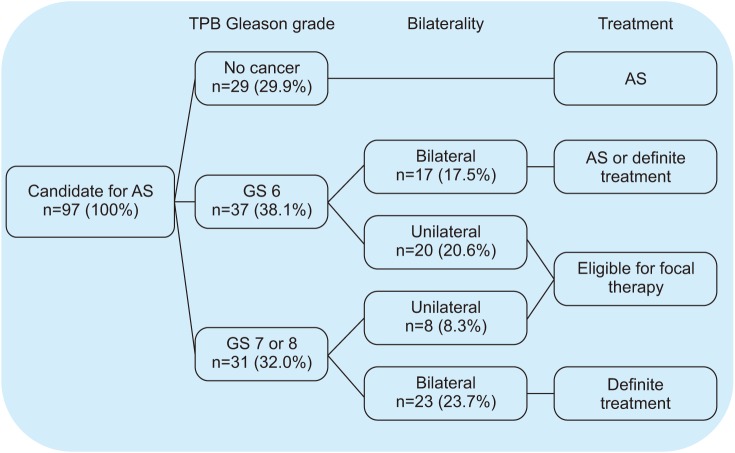

We retrospectively reviewed 155 patients who underwent TPB after previously negative results on TRUS-guided biopsy (n=58) or who were candidates for active surveillance (n=97) fulfilling the PRIAS criteria between May 2017 and November 2018. The patients' clinicopathologic data were reviewed, and the detection of clinically significant cancer (CSC) and upgrading of Gleason grade were identified.

RESULTS

The patients' median age and pre-TPB prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value were 65.0 years and 5.74 ng/mL, respectively. A median of 36 biopsy cores was obtained in each patient, with a median TPB core density of 0.88 cores/cm³. Of the 58 males with a previous negative result on TRUS-guided biopsy, prostate cancer (PCa) was detected in 17 males (29.3%), including 8 with CSC. Of the 97 patient candidates for active surveillance, upgrading of the Gleason grade was identified in 31 males (32.0%), 20 with a Gleason grade of 7 (3+4), 6 with a Gleason grade of 7 (4+3), and 5 with a Gleason grade of 8 (4+4). The overall complication rate was 14.8% (23/155), and there were no Clavien-Dindo grade 3 to 5 complications.

CONCLUSIONS

TPB helps to stratify the risk of PCa that was previously missed or underdiagnosed by TRUS-guided biopsy. TPB might be used as a diagnostic tool to determine risk classification and to help counsel patients with regard to treatment decisions.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Loeb S, Vellekoop A, Ahmed HU, Catto J, Emberton M, Nam R, et al. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013; 64:876–892. PMID: 23787356.

Article2. Song W, Choo SH, Sung HH, Han DH, Jeong BC, Seo SI, et al. Incidence and management of extended-spectrum betalactamase and quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli infections after prostate biopsy. Urology. 2014; 84:1001–1007. PMID: 25443894.

Article3. Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017; 71:618–629. PMID: 27568654.

Article4. Hayes JH, Ollendorf DA, Pearson SD, Barry MJ, Kantoff PW, Stewart ST, et al. Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: a decision analysis. JAMA. 2010; 304:2373–2380. PMID: 21119084.5. Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:126–131. PMID: 19917860.

Article6. Merrick GS, Delatore A, Butler WM, Bennett A, Fiano R, Anderson R, et al. Transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy identifies pathologic differences between very-low-risk and low-risk prostate cancer: implications for active surveillance. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017; 40:53–59. PMID: 25068472.7. Duffield AS, Lee TK, Miyamoto H, Carter HB, Epstein JI. Radical prostatectomy findings in patients in whom active surveillance of prostate cancer fails. J Urol. 2009; 182:2274–2278. PMID: 19758635.

Article8. Bokhorst LP, Valdagni R, Rannikko A, Kakehi Y, Pickles T, Bangma CH, et al. A decade of active surveillance in the PRIAS study: an update and evaluation of the criteria used to recommend a switch to active treatment. Eur Urol. 2016; 70:954–960. PMID: 27329565.

Article9. Krakowsky Y, Loblaw A, Klotz L. Prostate cancer death of men treated with initial active surveillance: clinical and biochemical characteristics. J Urol. 2010; 184:131–135. PMID: 20478589.

Article10. Park SY, Jung DC, Oh YT, Cho NH, Choi YD, Rha KH, et al. Prostate cancer: PI-RADS version 2 helps preoperatively predict clinically significant cancers. Radiology. 2016; 280:108–116. PMID: 26836049.

Article11. Voss J, Pal R, Ahmed S, Hannah M, Jaulim A, Walton T. Utility of early transperineal template-guided prostate biopsy for risk stratification in men undergoing active surveillance for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018; 121:863–870. PMID: 29239082.

Article12. Taira AV, Merrick GS, Bennett A, Andreini H, Taubenslag W, Galbreath RW, et al. Transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy as a staging procedure to select patients best suited for active surveillance. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013; 36:116–120. PMID: 22307210.

Article13. Thompson JE, Hayen A, Landau A, Haynes AM, Kalapara A, Ischia J, et al. Medium-term oncological outcomes for extended vs saturation biopsy and transrectal vs transperineal biopsy in active surveillance for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015; 115:884–891. PMID: 24989062.

Article14. Crawford ED, Rove KO, Barqawi AB, Maroni PD, Werahera PN, Baer CA, et al. Clinical-pathologic correlation between transperineal mapping biopsies of the prostate and three-dimensional reconstruction of prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013; 73:778–787. PMID: 23169245.

Article15. Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, Choyke P, Verma S, Villeirs G, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol. 2012; 22:746–757. PMID: 22322308.

Article16. Hansen N, Patruno G, Wadhwa K, Gaziev G, Miano R, Barrett T, et al. Magnetic resonance and ultrasound image fusion supported transperineal prostate biopsy using the Ginsburg protocol: technique, learning points, and biopsy results. Eur Urol. 2016; 70:332–340. PMID: 26995327.

Article17. Crawford ED, Wilson SS, Torkko KC, Hirano D, Stewart JS, Brammell C, et al. Clinical staging of prostate cancer: a computer-simulated study of transperineal prostate biopsy. BJU Int. 2005; 96:999–1004. PMID: 16225516.

Article18. Carroll PR, Parsons JK, Andriole G, Bahnson RR, Castle EP, Catalona WJ, et al. NCCN Guidelines insights: Prostate Cancer Early Detection, version 2.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016; 14:509–519. PMID: 27160230.

Article19. Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P, Jethava V, Zhang L, Jain S, et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:272–277. PMID: 25512465.

Article20. Nafie S, Wanis M, Khan M. The efficacy of transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy versus transperineal template biopsy of the prostate in diagnosing prostate cancer in men with previous negative transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy. Urol J. 2017; 14:3008–3012. PMID: 28299763.21. Nelson AW, Harvey RC, Parker RA, Kastner C, Doble A, Gnanapragasam VJ. Repeat prostate biopsy strategies after initial negative biopsy: meta-regression comparing cancer detection of transperineal, transrectal saturation and MRI guided biopsy. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e57480. PMID: 23460864.

Article22. Ayres BE, Montgomery BS, Barber NJ, Pereira N, Langley SE, Denham P, et al. The role of transperineal template prostate biopsies in restaging men with prostate cancer managed by active surveillance. BJU Int. 2012; 109:1170–1176. PMID: 21854535.

Article23. Pham KN, Porter CR, Odem-Davis K, Wolff EM, Jeldres C, Wei JT, et al. Transperineal template guided prostate biopsy selects candidates for active surveillance--how many cores are enough? J Urol. 2015; 194:674–679. PMID: 25963186.

Article24. Radtke JP, Kuru TH, Boxler S, Alt CD, Popeneciu IV, Huettenbrink C, et al. Comparative analysis of transperineal template saturation prostate biopsy versus magnetic resonance imaging targeted biopsy with magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion guidance. J Urol. 2015; 193:87–94. PMID: 25079939.

Article25. Vyas L, Acher P, Kinsella J, Challacombe B, Chang RT, Sturch P, et al. Indications, results and safety profile of transperineal sector biopsies (TPSB) of the prostate: a single centre experience of 634 cases. BJU Int. 2014; 114:32–37. PMID: 24053629.

Article26. Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994; 271:368–374. PMID: 7506797.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pain during Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Prostate Biopsy and the Role of Periprostatic Nerve Block: What Radiologists Should Know

- Magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion image-guided prostate biopsy: Current status of the cancer detection and the prospects of tailor-made medicine of the prostate cancer

- Value and Safety of Midazolam Anesthesia during Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Prostate Biopsy

- Comparison of Two Local Anesthestic Methods for Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Prostate Biopsy: Periprostatic Injection of Lidocaine and Rectal Instillation of Lidocaine Gel

- Infection after transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy