J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg.

2016 Dec;18(4):385-390. 10.7461/jcen.2016.18.4.385.

Severe Cerebral Vasospasm in Patients with Hyperthyroidism

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea. smyoon@sch.ac.kr

- KMID: 2367331

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7461/jcen.2016.18.4.385

Abstract

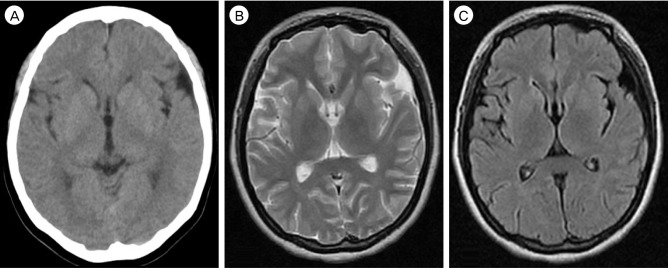

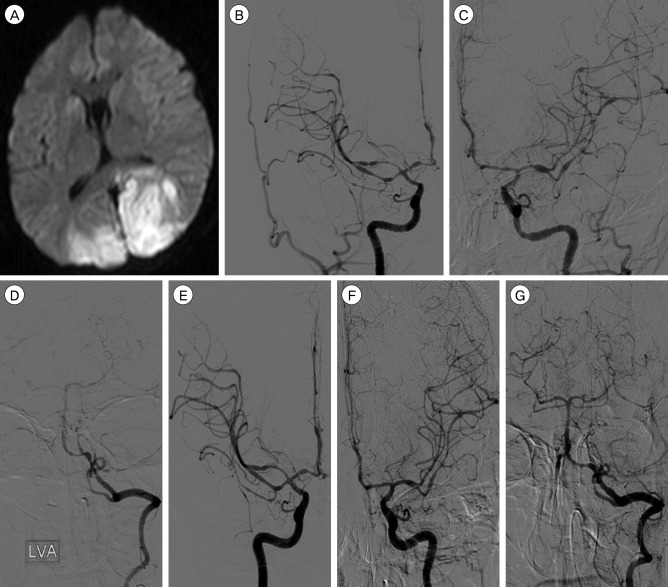

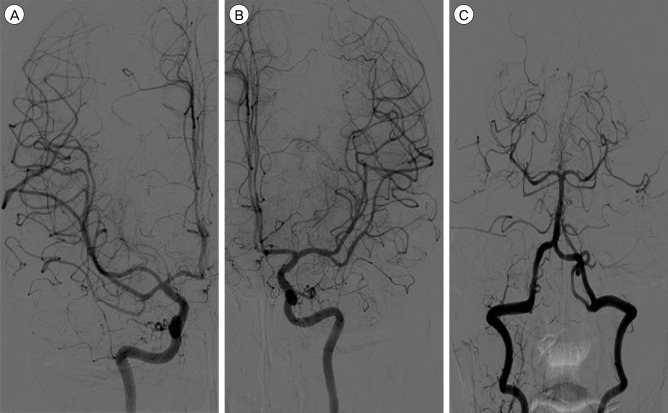

- Cerebral vasospasm associated with hyperthyroidism has not been reported to cause cerebral infarction. The case reported here is therefore the first of cerebral infarction co-existing with severe vasospasm and hyperthyroidism. A 30-year-old woman was transferred to our hospital in a stuporous state with right hemiparesis. At first, she complained of headache and dizziness. However, she had no neurological deficits or radiological abnormalities. She was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism 2 months ago, but she had discontinued the antithyroid medication herself three days ago. Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography showed cerebral infarction with severe vasospasm. Thus, chemical angioplasty using verapamil was performed two times, and antithyroid medication was administered. Follow-up angiography performed at 6 weeks demonstrated complete recovery of the vasospasm. At the 2-year clinical follow-up, she was alert with mild weakness and cortical blindness. Hyperthyroidism may influence cerebral vascular hemodynamics. Therefore, a sudden increase in the thyroid hormone levels in the clinical setting should be avoided to prevent cerebrovascular accidents. When neurological deterioration is noticed without primary cerebral parenchyma lesions, evaluation of thyroid function may be required before the symptoms occur.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris S, Thakkar V, Theofanis T, Hammer C, Hasan D, et al. Endovascular management of cerebral vasospasm following aneurysm rupture: outcomes and predictors in 116 patients. Clinl Neurol Neurosurg. 2014; 3. 118:26–31.

Article2. Chen JB, Lei D, He M, Sun H, Liu Y, Zhang H, et al. Clinical features and disease progression in moyamoya disease patients with Graves disease. J Neurosurg. 2015; 10. 123(4):848–855. PMID: 25859801.

Article3. Choi YH, Chung JH, Bae SW, Lee WH, Jeong EM, Kang MG, et al. Severe coronary artery spasm can be associated with hyperthyroidism. Coron Artery Dis. 2005; 5. 16(3):135–139. PMID: 15818081.

Article4. Chudleigh RA, Davies JS. Graves' thyrotoxicosis and coronary artery spasm. Postgrad Med J. 2007; 11. 83(985):e5. PMID: 17989261.

Article5. Duckworth JW, Wellman GC, Walters CL, Bevan JA. Aminergic histofluorescence and contractile responses to transmural electrical field stimulation and norepinephrine of human middle cerebral arteries obtained promptly after death. Circ Res. 1989; 8. 65(2):316–324. PMID: 2752543.

Article6. Hayashi K, Hirao T, Sakai N, Nagata I. JR-NET2 study group. Current status of endovascular treatment for vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage: analysis of JR-NET2. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2014; 54(Suppl 2):107–112.

Article7. Ichiki T. Thyroid hormone and vascular remodeling. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016; 3. 23(3):266–275. PMID: 26558400.

Article8. Inagawa T. Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2016; 1. 85:56–76. PMID: 26342775.

Article9. Kim SJ, Heo KG, Shin HY, Bang OY, Kim GM, Chung CS, et al. Association of thyroid autoantibodies with moyamoya-type cerebrovascular disease: a prospective study. Stroke. 2010; 1. 41(1):173–176. PMID: 19926842.10. Kramer DR, Winer JL, Pease BA, Amar AP, Mack WJ. Cerebral vasospasm in traumatic brain injury. Neurol Res Int. 2013; 2013:415813. PMID: 23862062.

Article11. Lassnig E, Berent R, Auer J, Eber B. Cardiogenic shock due to myocardial infarction caused by coronary vasospasm associated with hyperthyroidism. Inter J Cardiol. 2003; 8. 90(2-3):333–335.

Article12. Lee SW, Cho KI, Kim HS, Heo JH, Cha TJ. The Impact of subclinical hypothyroidism or thyroid autoimmunity on coronary vasospasm in patients without associated cardiovascular risk factors. Korean Circ J. 2015; 3. 45(2):125–130. PMID: 25810734.

Article13. Lei C, Wu B, Ma Z, Zhang S, Liu M. Association of moyamoya disease with thyroid autoantibodies and thyroid function: a case-control study and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2014; 7. 21(7):996–1001. PMID: 24684272.

Article14. Lincoln J. Innervation of cerebral arteries by nerves containing 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline. Pharmacol Ther. 1995; 68(3):473–501. PMID: 8788567.

Article15. Martin NA, Doberstein C, Zane C, Caron MJ, Thomas K, Becker DP. Posttraumatic cerebral arterial spasm: transcranial Doppler ultrasound, cerebral blood flow, and angiographic findings. J Neurosurg. 1992; 10. 77(4):575–583. PMID: 1527618.

Article16. Masani ND, Northridge DB, Hall RJ. Severe coronary vasospasm associated with hyperthyroidism causing myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995; 12. 74(6):700–701. PMID: 8541184.

Article17. Napoli R, Biondi B, Guardasole V, Matarazzo M, Pardo F, Angelini V, et al. Impact of hyperthyroidism and its correction on vascular reactivity in humans. Circulation. 2001; 12. 104(25):3076–3080. PMID: 11748103.

Article18. Ni J, Zhou LX, Wei YP, Li ML, Xu WH, Gao S, et al. Moyamoya syndrome associated with Graves' disease: a case series study. Ann Transl Med. 2014; 8. 2(8):77. PMID: 25333052.19. Ohba S, Nakagawa T, Murakami H. Concurrent Graves' disease and intracranial arterial stenosis/occlusion: special considerations regarding the state of thyroid function, etiology, and treatment. Neurosurg Rev. 2011; 7. 34(3):297–304. discussion 304. PMID: 21424208.

Article20. Owen PJ, Sabit R, Lazarus JH. Thyroid disease and vascular function. Thyroid. 2007; 6. 17(6):519–524. PMID: 17614771.

Article21. Pandey AS, Elias AE, Chaudhary N, Thompson BG, Gemmete JJ. Endovascular treatment of cerebral vasospasm: vasodilators and angioplasty. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2013; 11. 23(4):593–604. PMID: 24156852.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Myocardial Ischemia and Myocardial Injury Caused by Coronary Vasospasm Associated with Hyperthyroidism

- Prevention and Medical Management of Vasospasm

- Transcranial Doppler Monitoring in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- The Relationship Between CT Findings and Cerebral Vasospasm in Cerebral Aneursms

- Postoperative Vasospasm in Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm