Korean J Ophthalmol.

2010 Apr;24(2):83-88. 10.3341/kjo.2010.24.2.83.

Clinical Progress in Impending Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Wonju Christian Hospital, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea. bswhitey@.yonsei.ac.kr

- 2Yonsei Prime Eye Center, Wonju, Korea.

- KMID: 945999

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2010.24.2.83

Abstract

- PURPOSE

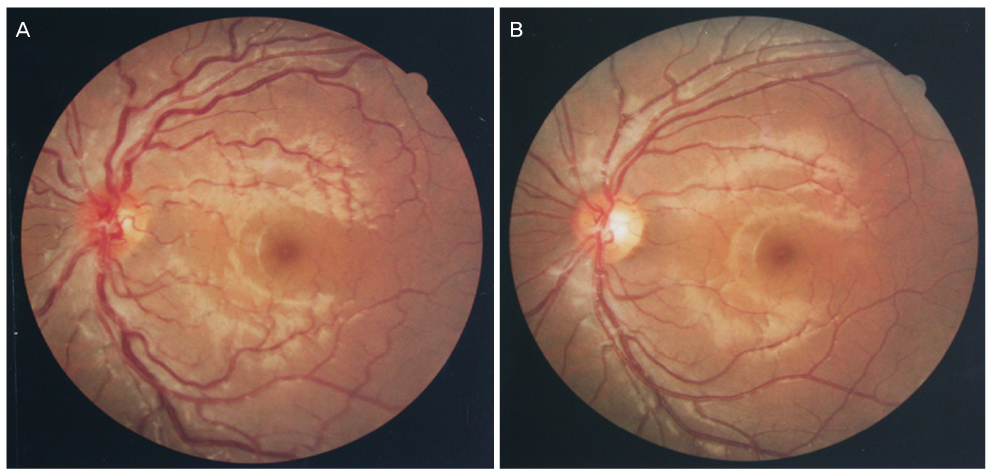

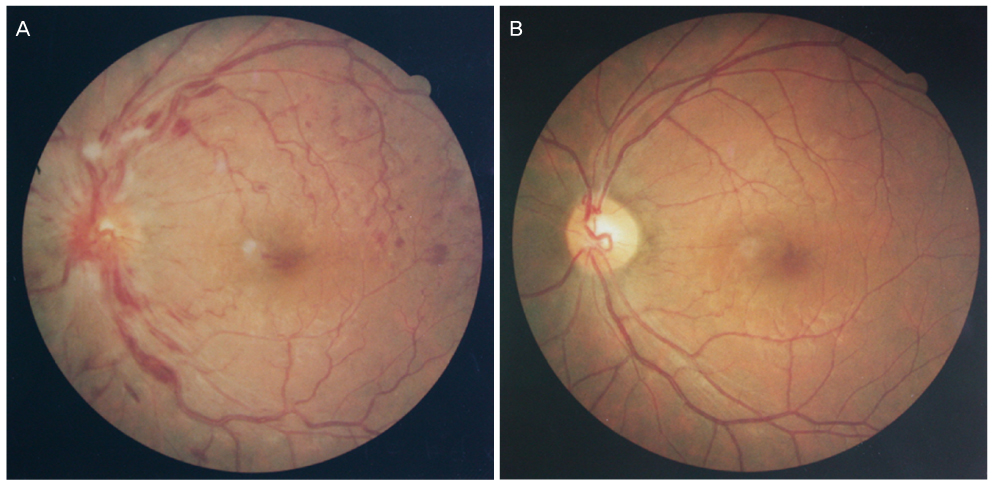

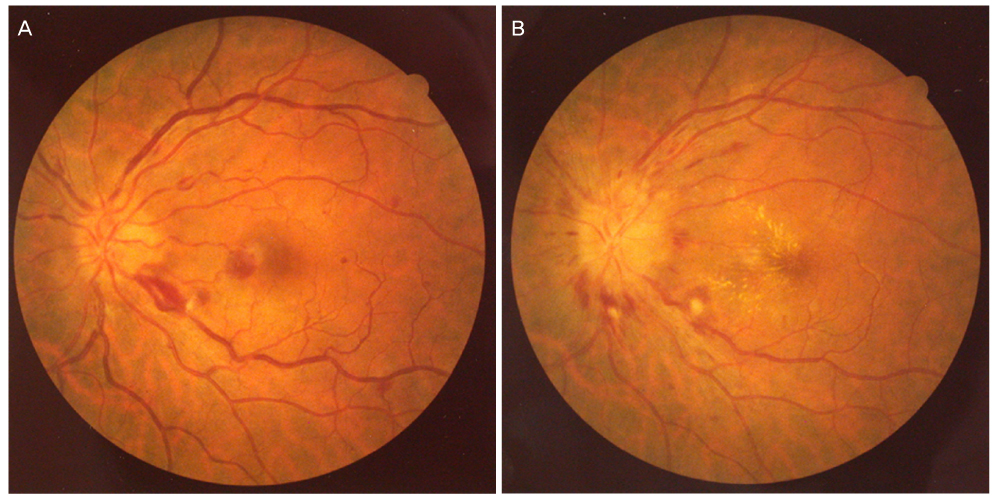

Impending central retinal vein occlusion is associated with mild or no loss of vision; however, its progress and vision prognosis have not been clearly defined until now. Therefore, we studied the progress and prognoses in patients with impending central retinal vein occlusion. METHODS: For this study, we selected ten subjects who had been diagnosed with impending central retinal vein occlusion, and we retrospectively reviewed their progress and prognoses. RESULTS: The average age of the subjects was 31.0 years (18 to 48 years). Eight patients were male and two were female. The average observational period was 5.5 months. Six out of ten subjects were found to have no underlying systemic disease, four subjects had underlying disease. All ten patients were affected unilaterally. When initially tested, the affected eyes showed an average vision of LogMar 0.30. The final vision test revealed an average of LogMar 0.04, which indicates good progress and prognosis. In one patient, retinal hemorrhage and macular edema progressively worsened after the diagnosis, and the patient was treated with radial optic neurotomy. CONCLUSIONS: The cases of impending central retinal vein occlusion that we observed seemed to primarily affect young patients with generally good prognoses. However, in some cases, the degrees of obstruction and hemorrhage increased as time progressed. This suggests that impending central retinal vein occlusion could develop into the prodromal phase of an acute attack.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Ocular and Systemic Manifestation of Amaurosis Fugax: Six-Year Observational Study

Tae Hwan Moon, Ju Byung Chae

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2015;56(5):732-736. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2015.56.5.732.Amaurosis Fugax Associated with Ipsilateral Internal Carotid Artery Agenesis

Jae Yun Sung, Kyoung Nam Kim, Hye Seon Jeong, Yeon Hee Lee

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2016;57(9):1484-1488. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2016.57.9.1484.

Reference

-

1. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996. 114:545–554.2. Gutman FA. Evaluation of a patient with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1983. 90:481–483.3. Magargal LE, Donoso LA, Sanborn GE. Retinal ischemia and risk of neovascularization following central retinal vein obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1982. 89:1241–1245.4. Gass JD. Stereoscopic atlas of macular disease: diagnosis and treatment. 1997. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby;546–555.5. Leber T. Graefe-Seamisch handbuch der gestamtem augenheikunde. 1877. Leibzig: Englelmann;551.6. Hayreh SS. So-called 'central retinal vein occlusion'. II. Venous stasis retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1976. 172:14–37.7. Mancall IT. Occlusion of central retinal vein. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1951. 46:668–675.8. Raitta C. Central venous and retinal venous occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1965. 83:1–123.9. Zegarra H, Gutman FA, Conforto J. The natural course of central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1979. 86:1931–1942.10. Lahey JM, Tunc M, Kearney J, et al. Laboatory evaluation of hypercoagulable state in patients with central retinal vein occlusion who are less than 56 years of age. Ophthalmology. 2002. 109:126–131.11. Williamson TH, Rumley A, Lowe GD. Blood viscosity, coagulation, and activated protein C resistance in central retinal vein occlusion: a population controlled study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996. 80:203–208.12. Cobo-Soriano R, Sanchez-Ramon S, Aparicio MJ, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and retinal thrombosis in patients without risk factors: a prospective case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999. 128:725–732.13. Glacet-Bernard A, Bayani N, Chretien P, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies in retinal vascular occlusion. A prospective study of 75 patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994. 112:790–795.14. Fong AC, Schatz H, McDonald HR, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion in young adults (papillophlebitis). Retina. 1992. 12:3–11.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Analysis of the Hemispheric Retinal Vein Occlusion

- A Case of Cilioretinal Artery Occlusion Associated with Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

- Progression of Impending Central Retinal Vein Occlusion to the Ischemic Variant Following Intravitreal Bevacizumab

- A Clinical Ana|ysis of Retinal Vein Occlusion

- Clinical Characteristics and Classifications of Retinal Vein Occlusion