J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Nov;31(11):1696-1702. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1696.

Facing Complaining Customer and Suppressed Emotion at Worksite Related to Sleep Disturbance in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea.

- 2The Institute for Occupational Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. flyinyou@gmail.com

- 3Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Incheon Worker's Health Center, Incheon, Korea.

- 5Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Institute Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 7Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 8Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2470263

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1696

Abstract

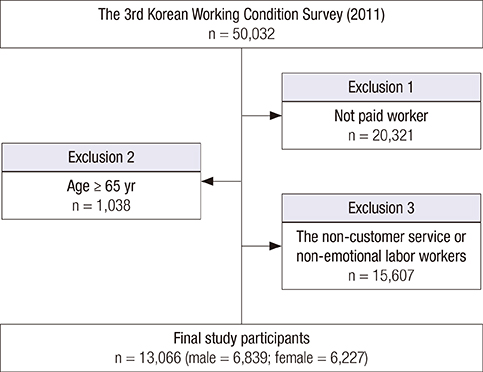

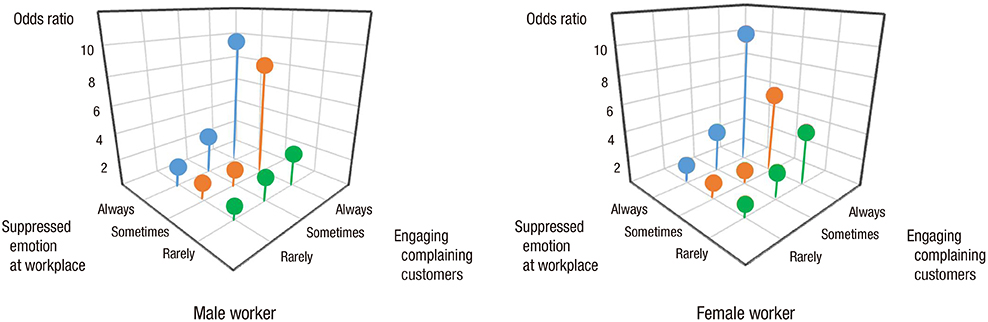

- This study aimed to investigate the effect of facing complaining customer and suppressed emotion at worksite on sleep disturbance among working population. We enrolled 13,066 paid workers (male = 6,839, female = 6,227, age < 65 years) in the 3rd Korean Working Condition Survey (2011). The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for sleep disturbance occurrence were calculated using multiple logistic regression models. Among workers in working environments where they always engage complaining customers had a significantly higher risk for sleep disturbance than rarely group (The OR [95% CI]; 5.46 [3.43-8.68] in male, 5.59 [3.30-9.46] in female workers). The OR (95% CI) for sleep disturbance was 1.78 (1.16-2.73) and 1.63 (1.02-2.63), for the male and female groups always suppressing their emotions at the workplace compared with those rarely group. Compared to those who both rarely engaged complaining customers and rarely suppressed their emotions at work, the OR (CI) for sleep disturbance was 9.66 (4.34-20.80) and 10.17 (4.46-22.07), for men and women always exposed to both factors. Sleep disturbance was affected by interactions of both emotional demands (engaging complaining customers and suppressing emotions at the workplace). The level of emotional demand, including engaging complaining customers and suppressing emotions at the workplace is significantly associated with sleep disturbance among Korean working population.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Emotional Labor and Burnout: A Review of the Literature

Da-Yee Jeung, Changsoo Kim, Sei-Jin Chang

Yonsei Med J. 2018;59(2):187-193. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.187.

Reference

-

1. Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press;1983.2. Grandey AA, Gabriel AS. Emotional labor at a crossroads: where do we go from here? Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2015; 2:323–349.3. Morris JA, Feldman DC. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad Manage Rev. 1996; 21:986–1010.4. Yoon SL, Kim JH. Job-related stress, emotional labor, and depressive symptoms among Korean nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2013; 45:169–176.5. Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I, Duberstein P, Muennig P. Emotion suppression and mortality risk over a 12-year follow-up. J Psychosom Res. 2013; 75:381–385.6. Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002; 6:97–111.7. Sun D, Shao H, Li C, Tao M. Sleep disturbance and correlates in menopausal women in Shanghai. J Psychosom Res. 2014; 76:237–241.8. Soldatos CR, Allaert FA, Ohta T, Dikeos DG. How do individuals sleep around the world? Results from a single-day survey in ten countries. Sleep Med. 2005; 6:5–13.9. Nomura K, Yamaoka K, Nakao M, Yano E. Social determinants of self-reported sleep problems in South Korea and Taiwan. J Psychosom Res. 2010; 69:435–440.10. Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008; 31:473–480.11. Katz DA, McHorney CA. Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158:1099–1107.12. Li Y, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Bixler EO, Sun Y, Zhou J, Ren R, Li T, Tang X. Insomnia with physiological hyperarousal is associated with hypertension. Hypertension. 2015; 65:644–650.13. Parthasarathy S, Vasquez MM, Halonen M, Bootzin R, Quan SF, Martinez FD, Guerra S. Persistent insomnia is associated with mortality risk. Am J Med. 2015; 128:268–275.e2.14. Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Sleep duration and chronic diseases among U.S. adults age 45 years and older: evidence from the 2010 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Sleep. 2013; 36:1421–1427.15. Verkasalo PK, Lillberg K, Stevens RG, Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep duration and breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:9595–9600.16. Walsh JK, Engelhardt CL. The direct economic costs of insomnia in the United States for 1995. Sleep. 1999; 22:Suppl 2. S386–93.17. Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Grégoire JP, Savard J, Baillargeon L. Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Med. 2009; 10:427–438.18. Stoller MK. Economic effects of insomnia. Clin Ther. 1994; 16:873–897.19. Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, Cauley JA. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2016; 25:21–30.20. Utsugi M, Saijo Y, Yoshioka E, Horikawa N, Sato T, Gong Y, Kishi R. Relationships of occupational stress to insomnia and short sleep in Japanese workers. Sleep. 2005; 28:728–735.21. Kim HC, Kim BK, Min KB, Min JY, Hwang SH, Park SG. Association between job stress and insomnia in Korean workers. J Occup Health. 2011; 53:164–174.22. Stepanski E, Zorick F, Roehrs T, Young D, Roth T. Daytime alertness in patients with chronic insomnia compared with asymptomatic control subjects. Sleep. 1988; 11:54–60.23. Richardson GS, Roth T. Future directions in the management of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62:Suppl 10. 39–45.24. Lushington K, Dawson D, Lack L. Core body temperature is elevated during constant wakefulness in elderly poor sleepers. Sleep. 2000; 23:504–510.25. Bonnet MH, Arand DL. 24-Hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep. 1995; 18:581–588.26. Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989; 262:1479–1484.27. Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007; 3:S7–10.28. Zhabenko N, Wojnar M, Brower KJ. Prevalence and correlates of insomnia in a Polish sample of alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012; 36:1600–1607.29. Morgan K. Daytime activity and risk factors for late-life insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2003; 12:231–238.30. Pigeon WR, Campbell CE, Possemato K, Ouimette P. Longitudinal relationships of insomnia, nightmares, and PTSD severity in recent combat veterans. J Psychosom Res. 2013; 75:546–550.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Anxiety, Depression and Sleep Disturbance among Customer-Facing Workers

- Effects of Aromatherapy and Foot Reflex Massage on Emotion, Sleep Disturbance, and Wandering Behavior in Older Adults with Dementia

- Symptoms, Mood and Sleep Disturbance in Hemodialysis

- Self-reported Pain Intensity and Disability Related to Sleep Disturbance and Fatigue in Patients with Low-Back Pain

- Influencing Factors of Sleep Disturbance in Pregnant Women