Korean Circ J.

2018 Sep;48(9):813-825. 10.4070/kcj.2017.0340.

Medical Resource Consumption and Quality of Life in Peripheral Arterial Disease in Korea: PAD Outcomes (PADO) Research

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 4Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 5Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea.

- 6Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 7Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University, Gospel Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 8Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Carollo Hospital, Suncheon, Korea.

- 9Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan, Korea.

- 10Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea.

- 11Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 12Outcomes Research and Real World Data, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea.

- 13Department of Biostatistics, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 14Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea. CDHLYJ@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2418806

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0340

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

We aimed to investigate the history of medical resource consumption and quality of life (QoL) in peripheral arterial disease (PAD) patients in Korea.

METHODS

This was a prospective, multi-center (23 tertiary-hospitals, division of cardiology), non-interventional study. Adult patients (age ≥20 years) suffering from PAD for the last 12-month were enrolled in the study if they met with any of following; 1) ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤0.9, 2) lower-extremity artery stenosis on computed tomography angiography ≥50%, or 3) peak-systolic-velocity-ratio (PSVR) on ultrasound ≥2.0. Medical chart review was used to assess patient characteristics/treatment patterns while the history of medical resource consumption and QoL data were collected using a patient survey. QoL was measured using EuroQoL-5-dimensions-3-level (EQ-5D-3L) score system, and the factors associated with QoL were analyzed using multiple linear regression analysis.

RESULTS

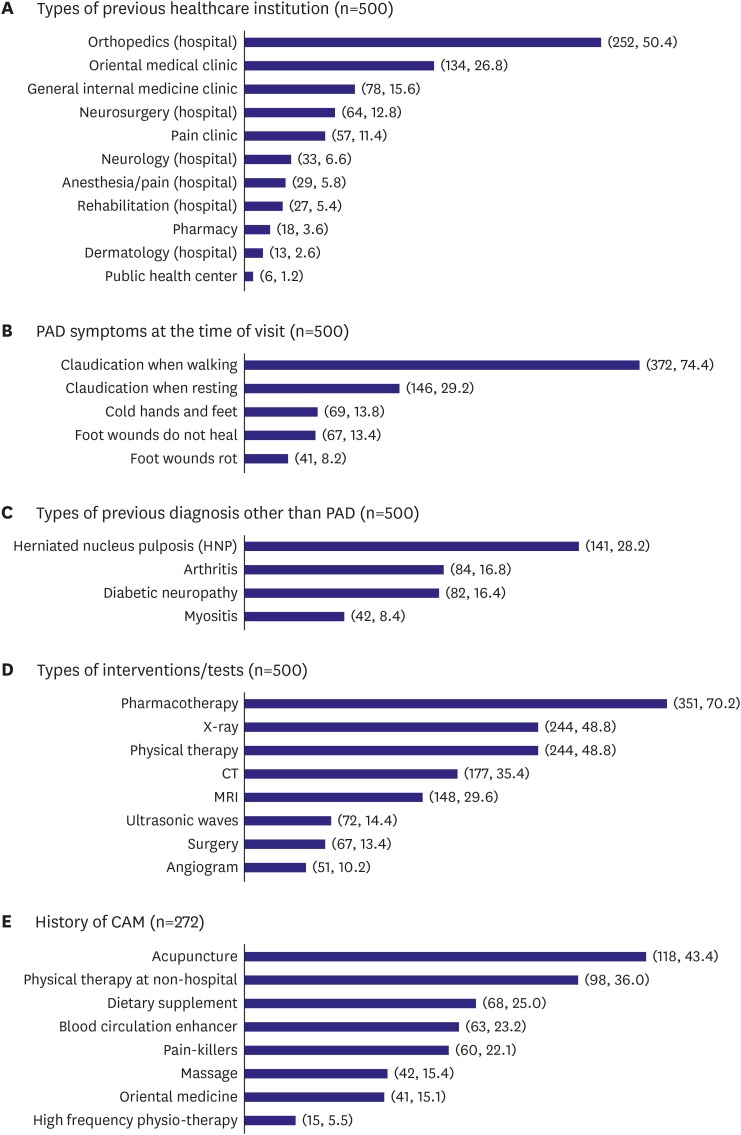

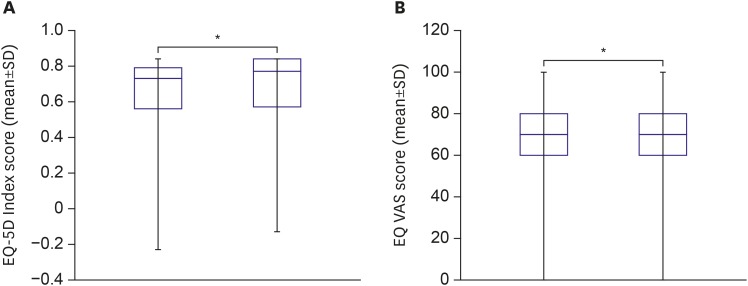

This study included 1,260 patients (age: 69.8 years, male: 77.0%). The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (74.8%), hyperlipidemia (51.0%) and diabetes-mellitus (50.2%). The 94.1% of the patients took pharmacotherapy including aspirin (76.2%), clopidogrel (53.3%), and cilostazol (33.6%). The 12.6% of the patients were receiving smoking cessation education/pharmacotherapy. A considerable number of patients (500 patients, 40.0%) had visit history to another hospital before diagnosis/treatment at the current hospital, with visits to orthopedic units (50.4%) being the most common. At the time, 29% (or higher) of the patients were already experiencing symptoms of critical limb ischemia. Baseline EQ-5D index and EQ VAS were 0.64±0.24 and 67.49±18.29. Factors significantly associated with QoL were pharmacotherapy (B=0.05053; p=0.044) compared to no pharmacotherapy, and Fontaine stage improvement/maintain stage I (B=0.04448; p < 0.001) compared to deterioration/maintain stage II-IV.

CONCLUSIONS

Increase in disease awareness for earlier diagnosis and provision of adequate pharmacotherapy is essential to reduce disease burden and improve QoL of Korean PAD patients.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Elucidation of the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease

Hyung Oh Kim, Weon Kim

Korean Circ J. 2018;48(9):826-827. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0155.Endovascular Therapy of Iliac Artery Disease: Stent Matters

Su Hong Kim

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(5):452-454. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0022.

Reference

-

1. Choi SH. Current management of peripheral arterial disease. J Korean Med Assoc. 2010; 53:228–235.2. Verma A, Prasad A, Elkadi GH, Chi YW. Peripheral arterial disease: evaluation, risk factor modification, and medical management. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2011; 18:74–84.3. Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. Circulation. 2004; 110:738–743. PMID: 15262830.4. Hankey GJ, Norman PE, Eikelboom JW. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease. JAMA. 2006; 295:547–553. PMID: 16449620.5. Rhee SY, Kim YS. Peripheral arterial disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J. 2015; 39:283–290. PMID: 26301189.6. Ko YG, Ahn CM, Min PK, et al. Baseline characteristics of the retrospective patient cohort in the Korean Vascular Intervention Society Endovascular Therapy in Lower Limb Artery Diseases (K-VIS ELLA) Registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:469–476. PMID: 28765738.7. Creager MA. Results of the CAPRIE trial: efficacy and safety of clopidogrel. Vasc Med. 1998; 3:257–260. PMID: 9892520.8. Becker GJ, McClenny TE, Kovacs ME, Raabe RD, Katzen BT. The importance of increasing public and physician awareness of peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002; 13:7–11. PMID: 11788688.9. Novo S. Classification, epidemiology, risk factors, and natural history of peripheral arterial disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2002; 4(Suppl 2):S1–S6.10. Izquierdo-Porrera AM, Gardner AW, Bradham DD, et al. Relationship between objective measures of peripheral arterial disease severity to self-reported quality of life in older adults with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2005; 41:625–630. PMID: 15874926.11. Issa SM, Hoeks SE. Health-related quality of life predicts long-term survival in patients with peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med. 2010; 15:163–169. PMID: 20483986.12. Hirsch AT, Hartman L, Town RJ, Virnig BA. National health care costs of peripheral arterial disease in the Medicare population. Vasc Med. 2008; 13:209–215. PMID: 18687757.13. Fowkes FG, Aboyans V, Fowkes FJ, McDermott MM, Sampson UK, Criqui MH. Peripheral artery disease: epidemiology and global perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017; 14:156–170. PMID: 27853158.14. Kang EJ, Shin HS, Park HJ, Jo MW, Kim NY. A valuation of health status using EQ-5D. Korean J Health Econ Policy. 2006; 12:19–43.15. Becker F, Robert-Ebadi H, Ricco JB, et al. Chapter I: definitions, epidemiology, clinical presentation and prognosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011; 42(Suppl 2):S4–S12.16. Liles DR, Kallen MA, Petersen LA, Bush RL. Quality of life and peripheral arterial disease. J Surg Res. 2006; 136:294–301. PMID: 17046794.17. Wieland LS, Manheimer E, Berman BM. Development and classification of an operational definition of complementary and alternative medicine for the Cochrane collaboration. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011; 17:50–59.18. Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Hyattsville: National Center for Health;2009.19. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Complementary therapies for peripheral arterial disease: systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2005; 181:1–7. PMID: 15939048.20. Lu JT, Creager MA. The relationship of cigarette smoking to peripheral arterial disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2004; 5:189–193. PMID: 15580157.21. Meijer WT, Grobbee DE, Hunink MG, Hofman A, Hoes AW. Determinants of peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160:2934–2938. PMID: 11041900.22. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2017; 135:e726–e779. PMID: 27840333.23. Lee YH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, et al. Cumulative smoking exposure, duration of smoking cessation, and peripheral arterial disease in middle-aged and older Korean men. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:94. PMID: 21310081.24. Coleman T, Agboola S, Leonardi-Bee J, Taylor M, McEwen A, McNeill A. Relapse prevention in UK Stop Smoking Services: current practice, systematic reviews of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis. [iii-iv.]. Health Technol Assess. 2010; 14:1–152.25. Klonizakis M, Crank H, Gumber A, Brose LS. Smokers making a quit attempt using e-cigarettes with or without nicotine or prescription nicotine replacement therapy: Impact on cardiovascular function (ISME-NRT) - a study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17:293. PMID: 28376818.26. Kang EJ, Ko SK. A catalogue of EQ-5D utility weights for chronic diseases among noninstitutionalized community residents in Korea. Value Health. 2009; 12(Suppl 3):S114–S117. PMID: 20586972.27. Ferreiro JL, Bhatt DL, Ueno M, Bauer D, Angiolillo DJ. Impact of smoking on long-term outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease treated with aspirin or clopidogrel: insights from the CAPRIE trial (Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:769–777. PMID: 24239662.28. Suzuki J, Shimamura M, Suda H, et al. Current therapies and investigational drugs for peripheral arterial disease. Hypertens Res. 2016; 39:183–191. PMID: 26631852.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Education of Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Peripheral Artery Disease

- Pharmacological Therapy of Peripheral Artery Disease in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Cardiovascular Risk Factor Management

- Epidemiology of Peripheral Arterial Diseases in Individuals with Diabetes Mellitus

- Factors associated with Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease

- Peripheral Arterial Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus