J Bone Metab.

2014 Feb;21(1):21-28.

Should We Prescribe Calcium Supplements For Osteoporosis Prevention?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. i.reid@auckland.ac.nz

Abstract

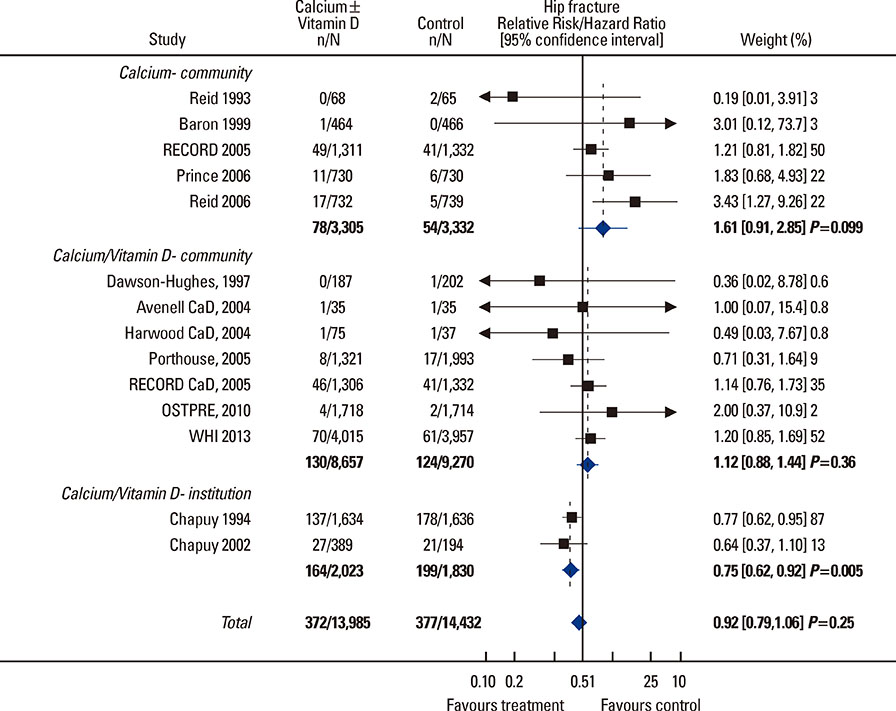

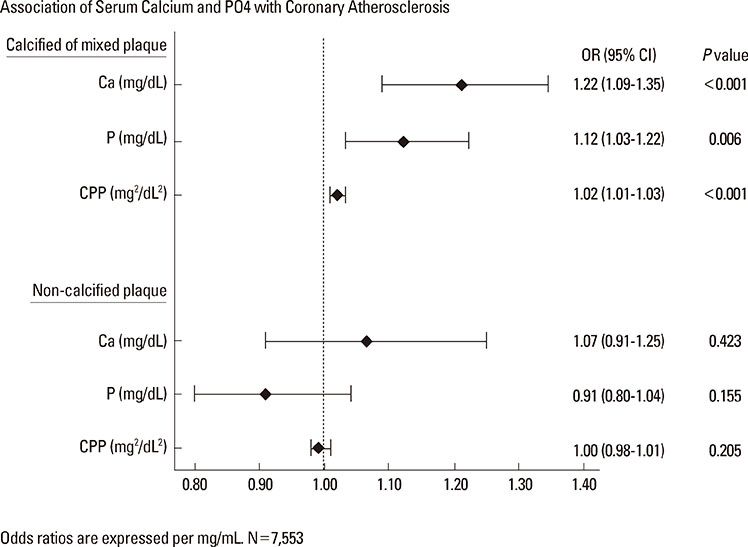

- Advocacy for the use of calcium supplements arose at a time when there were no other effective interventions for the prevention of osteoporosis. Their promotion was based on the belief that increasing calcium intake would increase bone formation. Our current understandings of the biology of bone suggest that this does not occur, though calcium does act as a weak antiresorptive. Thus, it slows postmenopausal bone loss but, despite this, recent meta-analyses suggest no significant prevention of fractures. In sum, there is little substantive evidence of benefit to bone health from the use of calcium supplements. Against this needs to be balanced the likelihood that calcium supplement use increases cardiovascular events, kidney stones, gastrointestinal symptoms, and admissions to hospital with acute gastrointestinal problems. Thus, the balance of risk and benefit seems to be consistently negative. As a result, current recommendations are to obtain calcium from the diet in preference to supplements. Dietary calcium intake has not been associated with the adverse effects associated with supplements, probably because calcium is provided in smaller boluses, which are absorbed more slowly since they come together with quantities of protein and fat, resulting in a slower gastric transit time. These findings suggest that calcium supplements have little role to play in the modern therapeutics of osteoporosis, which is based around the targeting of safe and effective anti-resorptive drugs to individuals demonstrated to be at increased risk of future fractures.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Anderson JJ, Roggenkamp KJ, Suchindran CM. Calcium intakes and femoral and lumbar bone density of elderly U.S. men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006 analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:4531–4539.

Article2. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Baron JA, et al. Calcium intake and hip fracture risk in men and women: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 86:1780–1790.

Article3. Reid IR, Mason B, Horne A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of calcium in healthy older women. Am J Med. 2006; 119:777–785.

Article4. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Delmas PD, et al. Effect of calcium and cholecalciferol treatment for three years on hip fractures in elderly women. BMJ. 1994; 308:1081–1082.

Article5. Salovaara K, Tuppurainen M, Kärkkäinen M, et al. Effect of vitamin D(3) and calcium on fracture risk in 65- to 71-year-old women: a population-based 3-year randomized, controlled trial--the OSTPRE-FPS. J Bone Miner Res. 2010; 25:1487–1495.

Article6. Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, et al. Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 365:1621–1628.

Article7. Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, et al. Effects of calcium supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:869–875.

Article8. Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:669–683.9. Murad MH, Drake MT, Mullan RJ, et al. Clinical review. Comparative effectiveness of drug treatments to prevent fragility fractures: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:1871–1880.

Article10. Reid IR, Bolland MJ. Calcium risk-benefit updated-New WHI analyses. Maturitas. 2014; 77:1–3.

Article11. Reid IR, Mason B, Horne A, et al. Effects of calcium supplementation on serum lipid concentrations in normal older women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2002; 112:343–347.

Article12. Reid IR, Horne A, Mason B, et al. Effects of calcium supplementation on body weight and blood pressure in normal older women: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005; 90:3824–3829.

Article13. Reid IR, Ames R, Mason B, et al. Effects of calcium supplementation on lipids, blood pressure, and body composition in healthy older men: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010; 91:131–139.

Article14. Bolland MJ, Barber PA, Doughty RN, et al. Vascular events in healthy older women receiving calcium supplementation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008; 336:262–266.

Article15. Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010; 341:c3691.

Article16. Hsia J, Heiss G, Ren H, et al. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2007; 115:846–854.

Article17. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, et al. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011; 342:d2040.

Article18. Radford LT, Bolland MJ, Gamble GD, et al. Subgroup analysis for the risk of cardiovascular disease with calcium supplements. Bonekey Rep. 2013; 2:293.

Article19. Sugerman DT. JAMA patient page. Osteoporosis. JAMA. 2014; 311:104.20. Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Calcium supplements: do they help or harm? Menopause. 2014; 21:106–108.21. Lewis J, Rejnmark L, Ivey K, et al. The cardiovascular safety of calcium supplementation with or without vitamin D in elderly women: a collaborative meta-analysis of published and unpublished trial level evidence from randomised controlled trials. In : ASBMR 2013 Annual Meeting; 2013 October 4-7; Baltimore Convention Center. Baltimore, MD: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.22. Larsen ER, Mosekilde L, Foldspang A. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community dwelling residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004; 19:370–378.

Article23. Jamal SA, Vandermeer B, Raggi P, et al. Effect of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382:1268–1277.

Article24. Ortiz A, Sanchez-Niño MD. The demise of calcium-based phosphate binders. Lancet. 2013; 382:1232–1234.

Article25. Bristow S, Stewart A, Gamble G, et al. Hydroxyapatite elevates serum calcium less than calcium salts but suppresses bone turnover comparably. IBMS BoneKEy. 2013; 10:S78.26. Rubin MR, Rundek T, McMahon DJ, et al. Carotid artery plaque thickness is associated with increased serum calcium levels: the Northern Manhattan study. Atherosclerosis. 2007; 194:426–432.

Article27. Shin S, Kim KJ, Chang HJ, et al. Impact of serum calcium and phosphate on coronary atherosclerosis detected by cardiac computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2873–2881.

Article28. Slinin Y, Blackwell T, Ishani A, et al. Serum calcium, phosphorus and cardiovascular events in post-menopausal women. Int J Cardiol. 2011; 149:335–340.

Article29. Lind L, Skarfors E, Berglund L, et al. Serum calcium: a new, independent, prospective risk factor for myocardial infarction in middle-aged men followed for 18 years. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997; 50:967–973.

Article30. Leifsson BG, Ahrén B. Serum calcium and survival in a large health screening program. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996; 81:2149–2153.

Article31. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Strontium ranelate (Protelos): risk of serious cardiac disorders-restricted indications, new contraindications, and warnings. Drug Safety Update. 2013; 6:S1.32. Kapustin AN, Davies JD, Reynolds JL, et al. Calcium regulates key components of vascular smooth muscle cell-derived matrix vesicles to enhance mineralization. Circ Res. 2011; 109:e1–e12.

Article33. James MF, Roche AM. Dose-response relationship between plasma ionized calcium concentration and thrombelastography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004; 18:581–586.

Article34. Lewis JR, Zhu K, Prince RL. Adverse events from calcium supplementation: relationship to errors in myocardial infarction self-reporting in randomized controlled trials of calcium supplementation. J Bone Miner Res. 2012; 27:719–722.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of Nano-sized Calcium on Intestinal Absorption and Bone Turnover

- Cardiovascular Impact of Calcium and Vitamin D Supplements: A Narrative Review

- Osteoporosis prevention and osteoporosis exercise in community-based public health programs

- Calcium and Cardiovascular Disease

- Current Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis