Clin Exp Vaccine Res.

2012 Jul;1(1):70-76. 10.7774/cevr.2012.1.1.70.

Development of a novel vaccine against canine parvovirus infection with a clinical isolate of the type 2b strain

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Veterinary Infectious Diseases, College of Veterinary Medicine, Konkuk University, Seoul, Korea. nhlee21@gmail.com

- KMID: 2278790

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7774/cevr.2012.1.1.70

Abstract

- PURPOSE

In spite of an extensive vaccination program, parvoviral infections still pose a major threat to the health of dogs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We isolated a novel canine parvovirus (CPV) strain from a dog with enteritis. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence analysis of the isolate showed that it is a novel type 2b CPV with asparagine at the 426th position and valine at the 555th position in VP2. To develop a vaccine against CPV infection, we passaged the isolate 4 times in A72 cells.

RESULTS

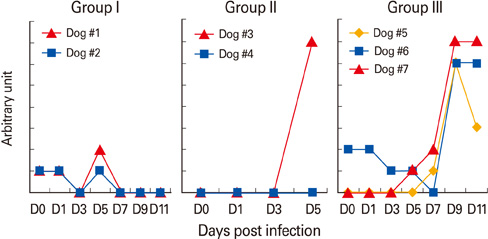

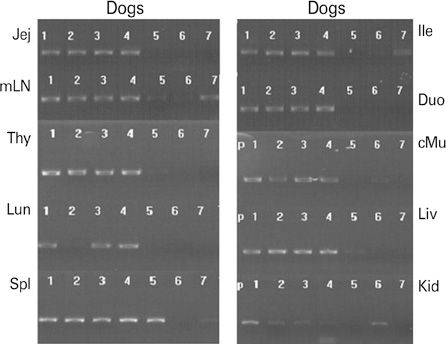

The attenuated isolate conferred complete protection against lethal homologous CPV infection in dogs such that they did not develop any clinical symptoms, and their antibody titers against CPV were significantly high at 7-11 days post infection.

CONCLUSION

These results suggest that the virus isolate obtained after passaging can be developed as a novel vaccine against paroviral infection.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Appel MJ, Scott FW, Carmichael LE. Isolation and immunisation studies of a canine parvo-like virus from dogs with haemorrhagic enteritis. Vet Rec. 1979. 105:156–159.

Article2. Parrish CR, Have P, Foreyt WJ, Evermann JF, Senda M, Carmichael LE. The global spread and replacement of canine parvovirus strains. J Gen Virol. 1988. 69(Pt 5):1111–1116.

Article3. Parrish CR. Host range relationships and the evolution of canine parvovirus. Vet Microbiol. 1999. 69:29–40.

Article4. Truyen U, Gruenberg A, Chang SF, Obermaier B, Veijalainen P, Parrish CR. Evolution of the feline-subgroup parvoviruses and the control of canine host range in vivo. J Virol. 1995. 69:4702–4710.

Article5. Binn LN, Lazar EC, Eddy GA, Kajima M. Recovery and characterization of a minute virus of canines. Infect Immun. 1970. 1:503–508.

Article6. Carmichael LE, Binn LN. New enteric viruses in the dog. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1981. 25:1–37.7. Carmichael LE, Schlafer DH, Hashimoto A. Minute virus of canines (MVC, canine parvovirus type-1): pathogenicity for pups and seroprevalence estimate. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994. 6:165–174.

Article8. Buonavoglia D, Cavalli A, Pratelli A, et al. Antigenic analysis of canine parvovirus strains isolated in Italy. New Microbiol. 2000. 23:93–96.9. Mochizuki M, Harasawa R, Nakatani H. Antigenic and genomic variabilities among recently prevalent parvoviruses of canine and feline origin in Japan. Vet Microbiol. 1993. 38:1–10.

Article10. Parrish CR, O'Connell PH, Evermann JF, Carmichael LE. Natural variation of canine parvovirus. Science. 1985. 230:1046–1048.

Article11. Parrish CR, Aquadro CF, Strassheim ML, Evermann JF, Sgro JY, Mohammed HO. Rapid antigenic-type replacement and DNA sequence evolution of canine parvovirus. J Virol. 1991. 65:6544–6552.

Article12. Pereira CA, Monezi TA, Mehnert DU, D'Angelo M, Durigon EL. Molecular characterization of canine parvovirus in Brazil by polymerase chain reaction assay. Vet Microbiol. 2000. 75:127–133.

Article13. Steinel A, Venter EH, Van Vuuren M, Parrish CR, Truyen U. Antigenic and genetic analysis of canine parvoviruses in southern Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1998. 65:239–242.14. Truyen U, Platzer G, Parrish CR. Antigenic type distribution among canine parvoviruses in dogs and cats in Germany. Vet Rec. 1996. 138:365–366.

Article15. Truyen U, Steinel A, Bruckner L, Lutz H, Mostl K. Distribution of antigen types of canine parvovirus in Switzerland, Austria and Germany. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2000. 142:115–119.16. Wang HC, Chen WD, Lin SL, Chan JP, Wong ML. Phylogenetic analysis of canine parvovirus VP2 gene in Taiwan. Virus Genes. 2005. 31:171–174.

Article17. Ikeda Y, Mochizuki M, Naito R, et al. Predominance of canine parvovirus (CPV) in unvaccinated cat populations and emergence of new antigenic types of CPVs in cats. Virology. 2000. 278:13–19.

Article18. Hirayama K, Kano R, Hosokawa-Kanai T, et al. VP2 gene of a canine parvovirus isolate from stool of a puppy. J Vet Med Sci. 2005. 67:139–143.

Article19. Martella V, Cavalli A, Pratelli A, et al. A canine parvovirus mutant is spreading in Italy. J Clin Microbiol. 2004. 42:1333–1336.

Article20. Nakamura M, Nakamura K, Miyazawa T, Tohya Y, Mochizuki M, Akashi H. Monoclonal antibodies that distinguish antigenic variants of canine parvovirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003. 10:1085–1089.

Article21. Decaro N, Elia G, Campolo M, et al. New approaches for the molecular characterization of canine parvovirus type 2 strains. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2005. 52:316–319.

Article22. Chang SF, Sgro JY, Parrish CR. Multiple amino acids in the capsid structure of canine parvovirus coordinately determine the canine host range and specific antigenic and hemagglutination properties. J Virol. 1992. 66:6858–6867.

Article23. Truyen U, Parrish CR, Harder TC, Kaaden OR. There is nothing permanent except change. The emergence of new virus diseases. Vet Microbiol. 1995. 43:103–122.

Article24. Hirasawa T, Kaneshige T, Mikazuki K. Sensitive detection of canine parvovirus DNA by the nested polymerase chain reaction. Vet Microbiol. 1994. 41:135–145.

Article25. Hoare CM, DeBouck P, Wiseman A. Immunogenicity of a low-passage, high-titer modified live canine parvovirus vaccine in pups with maternally derived antibodies. Vaccine. 1997. 15:273–275.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Isolation and identification of canine parvovirus type 2b in Korean dogs

- Evaluation of Commercial Immunochromatographic Test Kits for the Detection of Canine Distemper Virus

- Clinical Characteristics of Human Parvovirus B19 Infection in Children

- Recharacterization of the Canine Adenovirus Type 1 Vaccine Strain based on the Biological and Molecular Properties

- Evaluation of commercial immunochromatography test kits for diagnosing canine parvovirus