Korean Circ J.

2008 Feb;38(2):101-109. 10.4070/kcj.2008.38.2.101.

The Comparative Clinical Effects of Valsartan and Ramipril in Patients With Heart Failure

- Affiliations

-

- 1The Heart Center of Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea. myungho@chollian.net

- 2Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan, Korea.

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Gunsan Medical Center, Gunsan, Korea.

- 4Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Presbyterian Medical Center, Jeonju, Korea.

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, College of Seonam University, Namwon, Korea.

- 6Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Gwangju Christian Hospital, Gwangju, Korea.

- KMID: 2225846

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2008.38.2.101

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) has emerged as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) for the treatment of heart failure. This study aimed at comparing the effectiveness and safety of valsartan with ramipril in patients with heart failure, and these patients were hospitalized at Chonnam National University Hospital, Wonkwang University Hospital, Gunsan Medical Center, Presbyterian Medical Center, Seonam University Hospital and Gwangju Christian Hospital.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Between March 2005 and March 2007, 82 patients (60.5+/-12.4 years, 59 males) who complained of class II to IV dyspnea, according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, and who had low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 50% were randomly allocated to valsartan or ramipril. After 6 months, the clinical symptoms, vital signs, biochemical tests and echocardiography were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

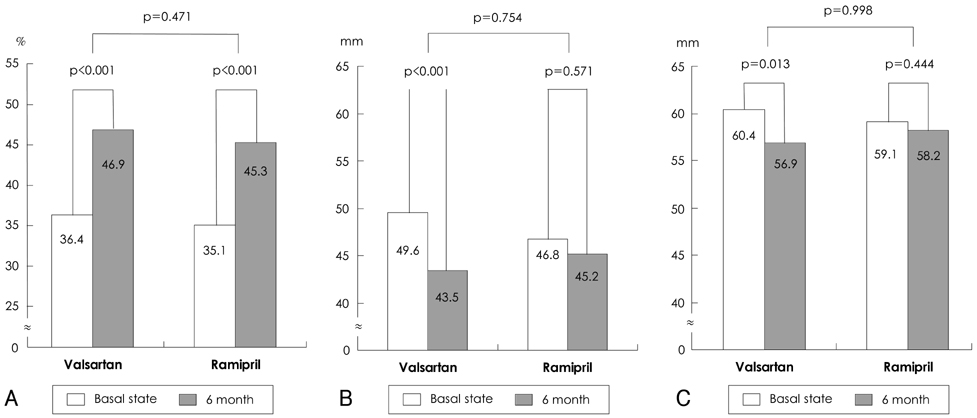

The NYHA class was improved in both groups (the valsartan group: 2.31+/-0.51 vs. 1.46+/-0.58, p<0.001; the ramipril group: 2.21+/-0.55 vs. 1.61+/-0.50, p<0.001). The incidence of cough, as measured by the cough index, was significantly lower in the valsartan group than in the ramipril group (p=0.045). The LVEF was improved in both groups (the valsartan group: 36.4+/-8.5% vs. 46.9+/-12.9%, p<0.001; the ramipril group: 35.1+/-8.5% vs. 45.3+/-11.2%, p<0.001). The improvements of the left ventricular end-systolic dimension (p=0.754) and end-diastolic dimension (p=0.998) were not different between the two groups. N-terminal Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level was improved in both groups (the valsartan group: 2619.6+/-4213.5 vs. 995.4+/-2186.0 pg/mL, p=0.012; the ramipril group: 3267.9+/-4320.0 vs. 828.1+/-1232.8 pg/mL, p=0.009), and there was no difference between the groups (p=0.877).

CONCLUSION

Both valsartan and ramipril were effective treatments, with relatively low adverse events, in patients with heart failure.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ryu WS, Kim SW, Kim CJ. Overview of the renin-angiotensin system. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:91–96.2. Pfeffer MA, Braundwald E, Moye LA, et al. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: results of the survival and ventricular enlargement (SAVE) trial. N Engl J Med. 1992. 327:669–677.3. Pitt B, Segal R, Martinez FA, et al. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril in patients over 65 with heart failure. Lancet. 1997. 349:747–752.4. Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001. 345:1667–1675.5. Yusuf S, Ostergren JB, Gerstein HC, et al. Effects of candesartan on the development of a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2005. 112:48–53.6. Urata H, Boehm KD, Philip A, et al. Cellular localization and regional distribution of an angiotensin II forming chymase in the heart. J Clin Invest. 1993. 91:1269–1281.7. Morice AH, Lowry R, Brouwn MJ, Higinbotam T. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and the cough reflex. Lancet. 1987. 2:1116–1118.8. Minisi AJ, Thames MD. Distribution of left ventricular sympathetic afferent demonstrated by reflex responses to transmural myocardial ischemia and to intracoronary and epicardial bradykinin. Circulation. 1993. 87:240–246.9. Critchley JAJH, Gilchrist N, Ikeda L, et al. A randomized, double-masked comparison of the antihypertensive efficacy and safety of combination therapy with losartan and hydrochlorothiazide versus captopril and hydrochlorothiazide in elderly and younger patients. Curr Ther Res. 1996. 57:392–407.10. Anderson GH Jr, Streeten DH, Dalakos TG. Pressure response to 1-sar-8-ala-angiotensin II (saralasin) in hypertensive subjects. Circ Res. 1977. 40:243–250.11. Kang PM, Landau AJ, Eberhardt RT, Frishman WH. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists: a new approach to blockade of the rennin-angiotensin system. Am Heart J. 1994. 127:1388–1401.12. Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:1893–1906.13. Bristow MR. Why does the myocardium fail?: insights from basic science. Lancet. 1998. 352:Suppl 1. SI8–SI14.14. Swan HJ. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction in the acute phases of myocardial ischaemia and infarction and in the later phases of recovery: function follows morphology. Eur Heart J. 1993. 14:48–56.15. Mitchell GF, Pfeffer MA. The role of geometry in left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev. 1995. 3:71–78.16. Taylor GJ, Humphries JO, Mellits ED, et al. Predictors of clinical course, coronary anatomy and left ventricular function after recovery from acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980. 62:960–970.17. White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987. 76:44–51.18. Kim KH, Jeong MH, Park JC, et al. The comparison among low and high doses of imidapril, and combined imidapril with losartan in patients with ischemic heart failure after coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2000. 30:965–972.19. Rhew JY, Jeong MH, Lee KY, et al. The clinical effects of a combined agent including losartan and hydrochlorthiazide, Hyzaar®, in patients with ischemic heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2002. 32:349–354.20. Park HY, Jeong MH, Lee SH, et al. The effects of cilazapril on left ventricular remodeling after coronary intervention in patients with ischemic heart failure. Korean Circ J. 1998. 28:1964–1972.21. Lim SC, Rhee JA, Jeong MH, et al. Predictive factors for the recovery of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:113–118.22. de Denus S, Pharand C, Williamson DR. Brain natriuretic peptide in the management of heart failure: the versatile neurohormone. Chest. 2004. 125:652–668.23. Groenning BA, Nilsson JC, Sondergaard L, Kjaer A, Larsson HB, Hildebrandt PR. Evaluation of impaired left ventricular ejection fraction and increased dimensions by multiple neurohumoral plasma concentrations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001. 3:699–708.24. Yan RT, White M, Yan AT, et al. Usefulness of temporal changes in neurohormones as markers of ventricular remodeling and prognosis in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure receiving either candesartan or enalapril or both. Am J Cardiol. 2005. 96:698–704.25. Talwar S, Squire IB, Downie PF, et al. Profile of plasma N-terminal proBNP following acute myocardial infarction: correlation with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2000. 21:1514–1521.26. Kurtz TW, Pravenec M. Antidiabetic mechanisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists: beyond the renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2004. 22:2253–2261.27. Lindholm LH, Ibsen H, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. Risk of new-onset diabetes in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study. J Hypertens. 2002. 20:1879–1886.28. Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine. Lancet. 2004. 363:2022–2031.29. Ogihara T, Asano T, Ando K, et al. Angiotensin II-induced insulin resistance is associated with enhanced insulin signaling. Hypertension. 2002. 40:872–879.30. Kasama S, Toyama T, Hatori T, et al. Comparative effects of valsartan and enalapril on cardiac sympathetic nerve activity and plasma brain natriuretic peptide in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart. 2006. 92:625–630.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Sacubitril/Valsartan in Asian Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

- Antihypertensive Effect of Ramipril in Patients with Essential Hypertension

- Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor for the treatment of heart failure: a review of recent evidence

- ECG Monitoring of Reactions to Sacubitril-valsartan in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

- Effects of Ramipril on Vascular Response in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease