Korean Diabetes J.

2008 Apr;32(2):157-164. 10.4093/kdj.2008.32.2.157.

The Biochemical Markers of Coronary Heart Disease Correlates Better to Metabolic Syndrome Defined by WHO than by NCEP-ATP III or IDF in Korean Type 2 Diabetic Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Endocrinology, College of Medicine, Konyang University, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University College of Medicine, Korea.

- KMID: 2222512

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/kdj.2008.32.2.157

Abstract

-

BACKGROUND: Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is constellation of cardiovascular risk factors. There are three typically used definitions of MetS proposed by WHO, IDF and NCEP-ATP III. We conducted this study to compare the associations of MetS by WHO, IDF and NCEP-ATP III definition to various metabolic markers of coronary heart diseases in Korean type 2 diabetes patients.

METHODS

We enrolled 151 Korean type 2 diabetes patients in one hospital. Anthropometric and biochemical parameters, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), homocysteine, uric acid were measured. And then, we divided MetS group from non-MetS group according to three other definitions.

RESULTS

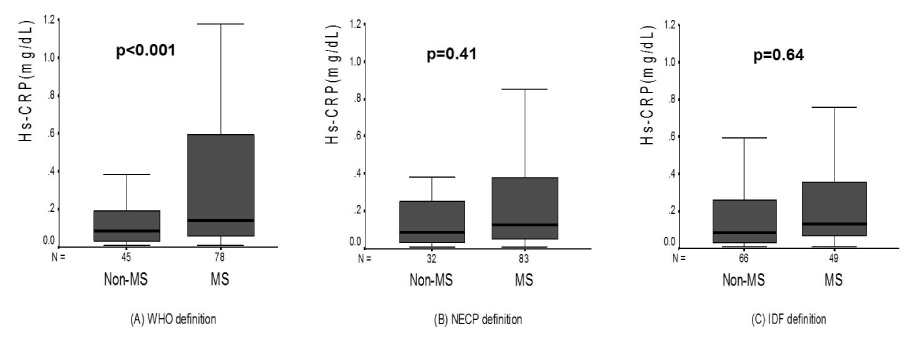

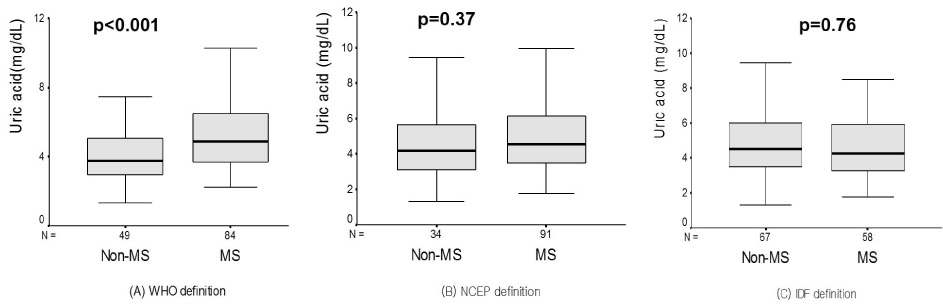

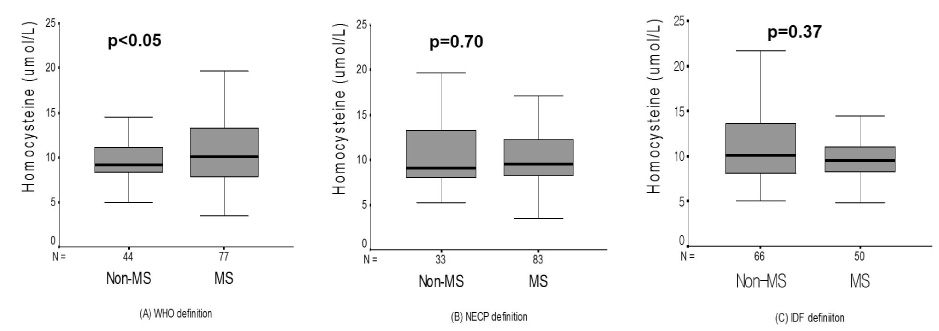

Serum hsCRP level was higher in those with MetS group than non-MetS group by WHO definition (0.33 +/- 0.36 mg/dL vs 0.18 +/- 0.26 mg/dL, P < 0.001). But, there are no difference in MetS group and non-MetS group by IDF and NCEP-ATPIII definition. (By IDF, 0.28 +/- 0.31 mg/dL vs 0.25 +/- 0.34 mg/dL, P = 0.64; By NCEP-ATP III, 0.28 +/- 0.33 mg/dL vs 0.22 +/- 0.32 mg/dL, P = 0.41). Uric acid and homocysteine levels were higher in those with MetS by WHO definition (P < 0.05). Similarly, analyses according to IDF and NCEP ATP III definition showed no significant difference.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, WHO definition of MetS has a stronger relationship with the biochemical markers of coronary heart disease in Korean type 2 diabetes patients.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Isomass B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Lissen M, Taskinen MR, Groop L. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001. 24:683–689.

Article2. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002. 288:2709–2716.

Article3. Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988. 37:1595.

Article4. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998. 15:539–553.

Article5. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001. 285:2486–2497.6. Zimmet PZ, Alberti KG, Shaw J. International Diabetes Federation: the IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes voice. 2005. 50:31–33.7. Otsuka T, Kawada T, Katsumata M, Ibuki C, Kusama Y. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is associated with the risk of coronary heart disease as estimated by the Framingham Risk Score in middle-aged Japanese men. Int J Cardiol. 2007. 129:245–250.

Article8. Fowler B. Homocystein--an independent risk factor for cardiovascular and thrombotic diseases. Ther Umsch. 2005. 62(9):641–646.9. Strasak AM, Kelleher CC, Brant LJ, Rapp K, Ruttmann E, Concin H, Diem G, Pfeiffer KP, Ulmer H. Serum uric acid is an independent predictor for all major forms of cardiovascular death in 28,613 elderly women: A prospective 21-year follow-up study. Int J Cardiology. 2008. 125:232–239.

Article11. Simone GD, Devereux RB, Chinali M, Best LG, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Resnick HE. Prognostic impact of metabolic syndrome by different definitions in a population with high prevalence of obesity and diabetes: The strong heart study. Diabetes care. 2007. 30:1851–1856.

Article12. Turner RC, Millns H, Neil HA, Stratton IM, Manley SE, Matthews DR, Holman PP. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS: 23). BMJ. 1998. 316:823–828.

Article13. Alberti GM, Zimmet PZ, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome a new worldwide definition. The Lancet. 2005. 24:1059–1062.14. Stern MP, Williams K, Gonzalez-Villalpando C, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. Does the metabolic syndrome improve identification of individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care. 2004. 27:2676–2681.

Article15. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002. 288:2709–2716.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Biochemical Markers of Coronary Heart Disease Correlates Better to Metabolic Syndrome Defined by WHO than by NCEP-ATP III or IDF in Korean Type 2 Diabetic Patients

- The Biochemical Markers of Coronary Heart Disease Correlates Better to Metabolic Syndrome Defined by WHO than by NCEP-ATP III or IDF in Korean Type 2 Diabetic Patients

- The Diagnostic Criteria of Metabolic Syndrome and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease according to Definitions in Men

- Association between Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome in Healthy Adults: Comparison of the NCEP-ATP III and New IDF Definition

- Metabolic Syndrome Defined by International Diabetes Federation (IDF) or National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) and Insulin Resistance