Korean J Leg Med.

2014 Aug;38(3):103-112. 10.7580/kjlm.2014.38.3.103.

Remarkable Postmortem CT Findings in Forensic Autopsy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Forensic Investigation, Seoul Institute, National Forensic Service, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Medical Examiner's Office, National Forensic Service, Wonju, Korea. rudany@korea.kr

- 3Department of Radiology, Soonchunhyang University Hospital Bucheon, Bucheon, Korea.

- 4Seoul Institute, National Forensic Service, Seoul, Korea.

- 5National Forensic Service, Wonju, Korea.

- KMID: 2082760

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7580/kjlm.2014.38.3.103

Abstract

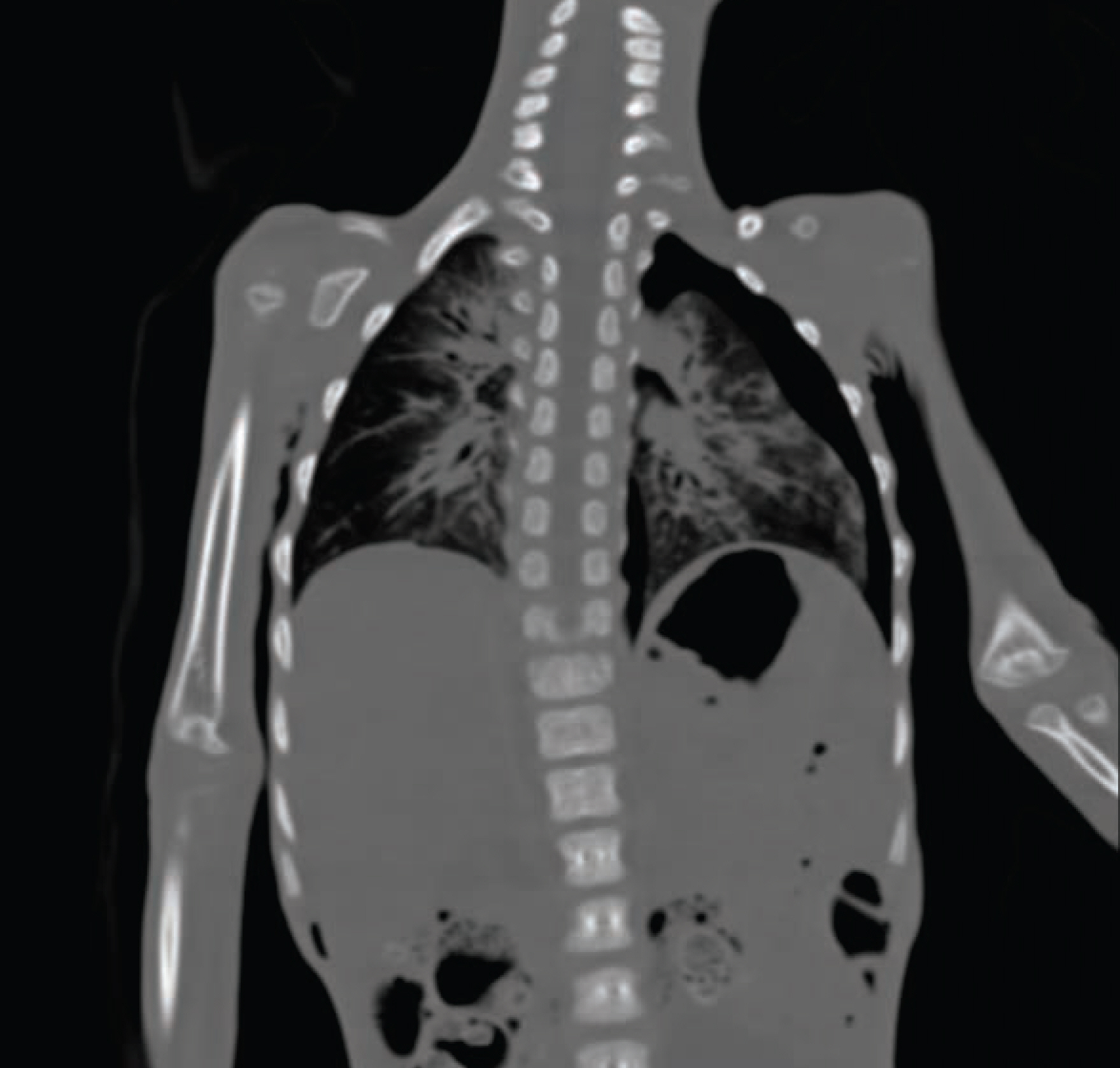

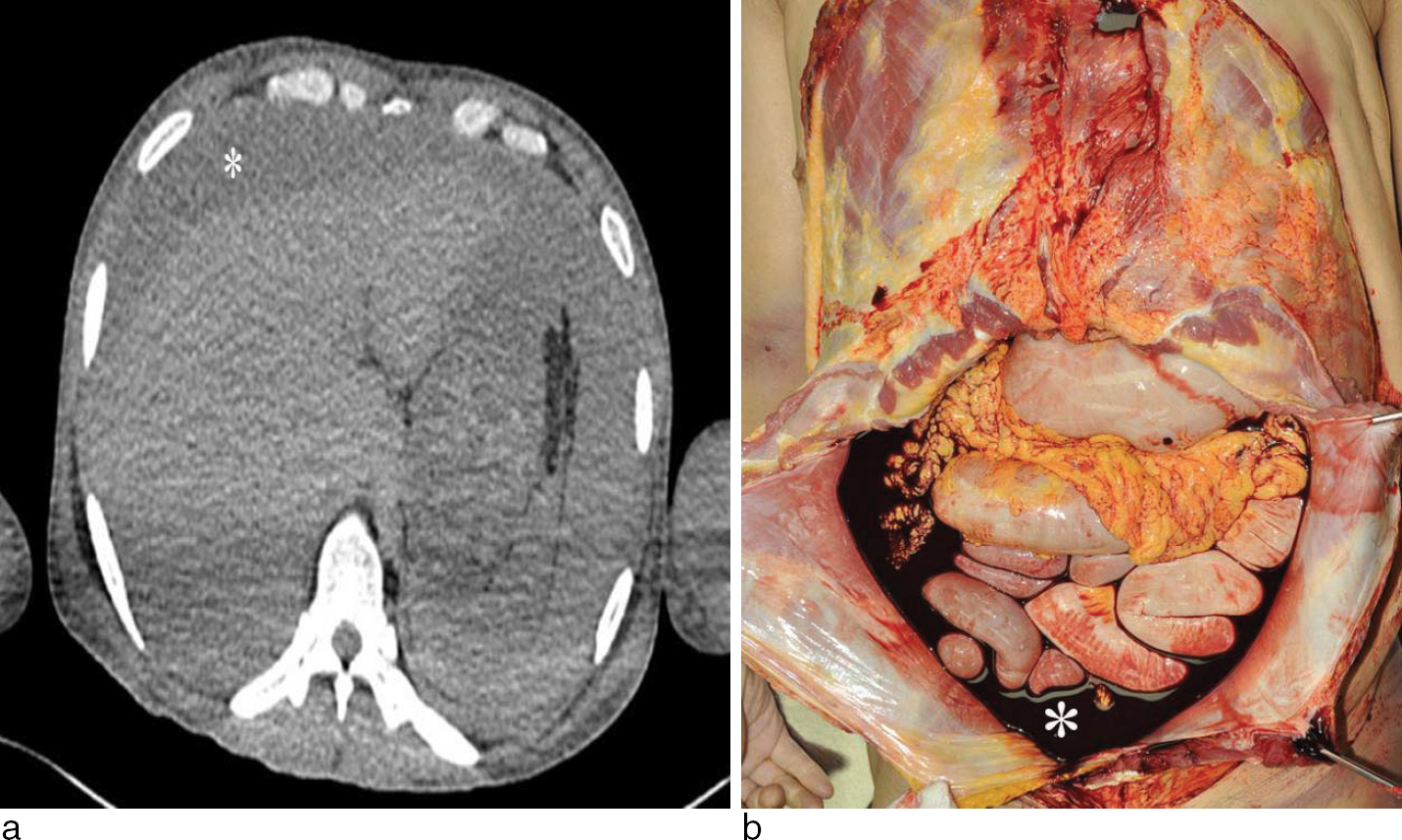

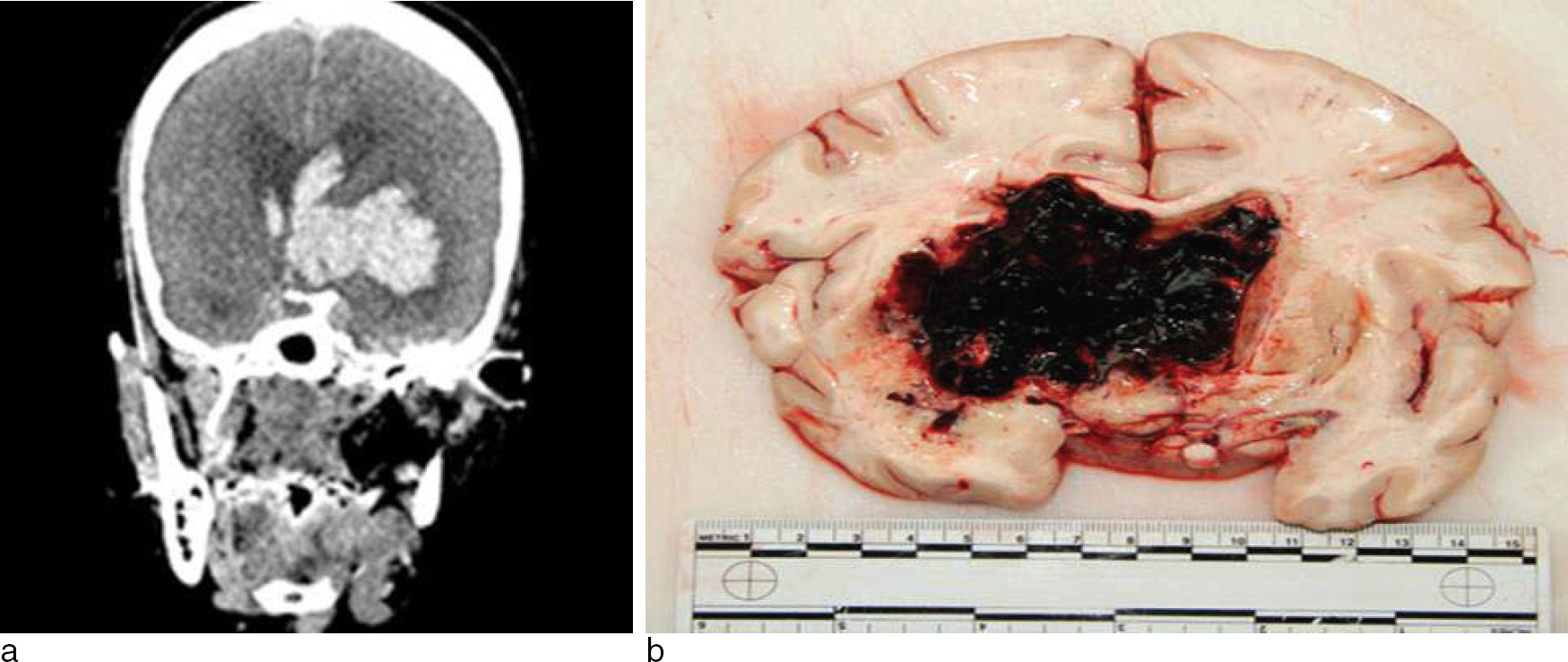

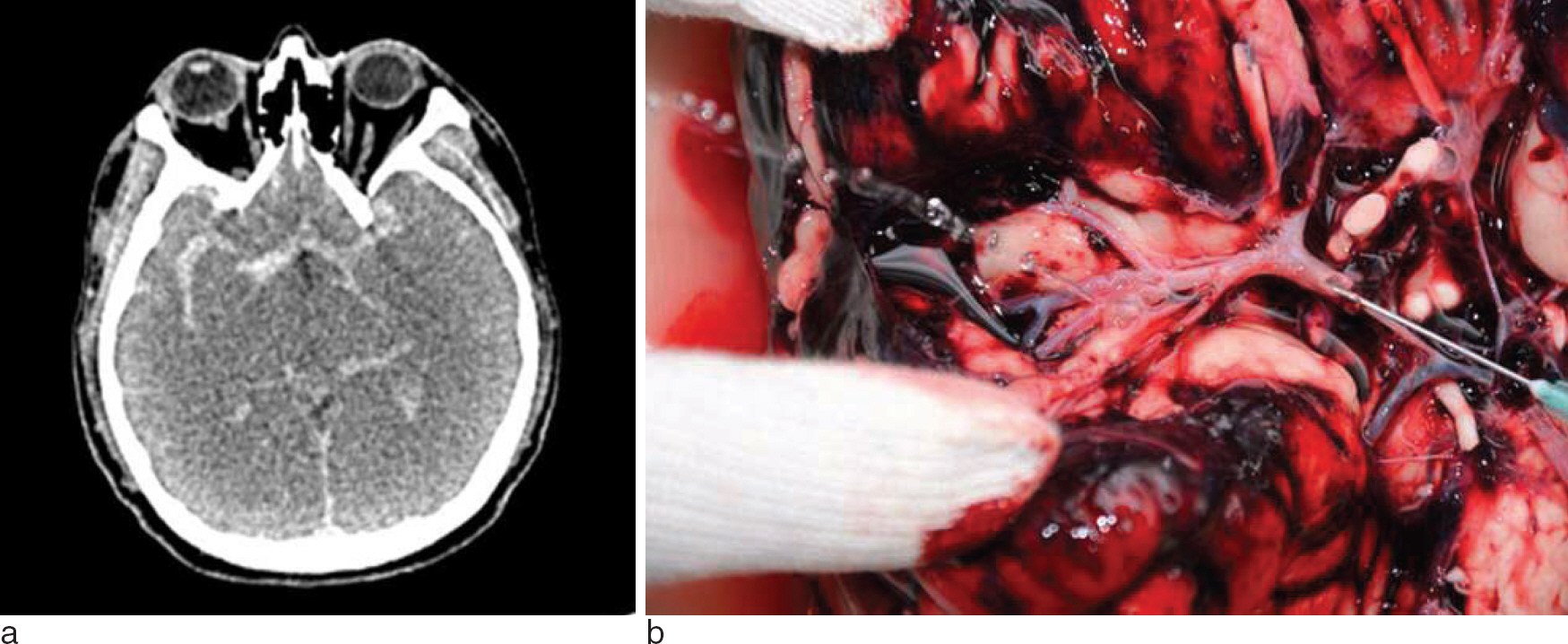

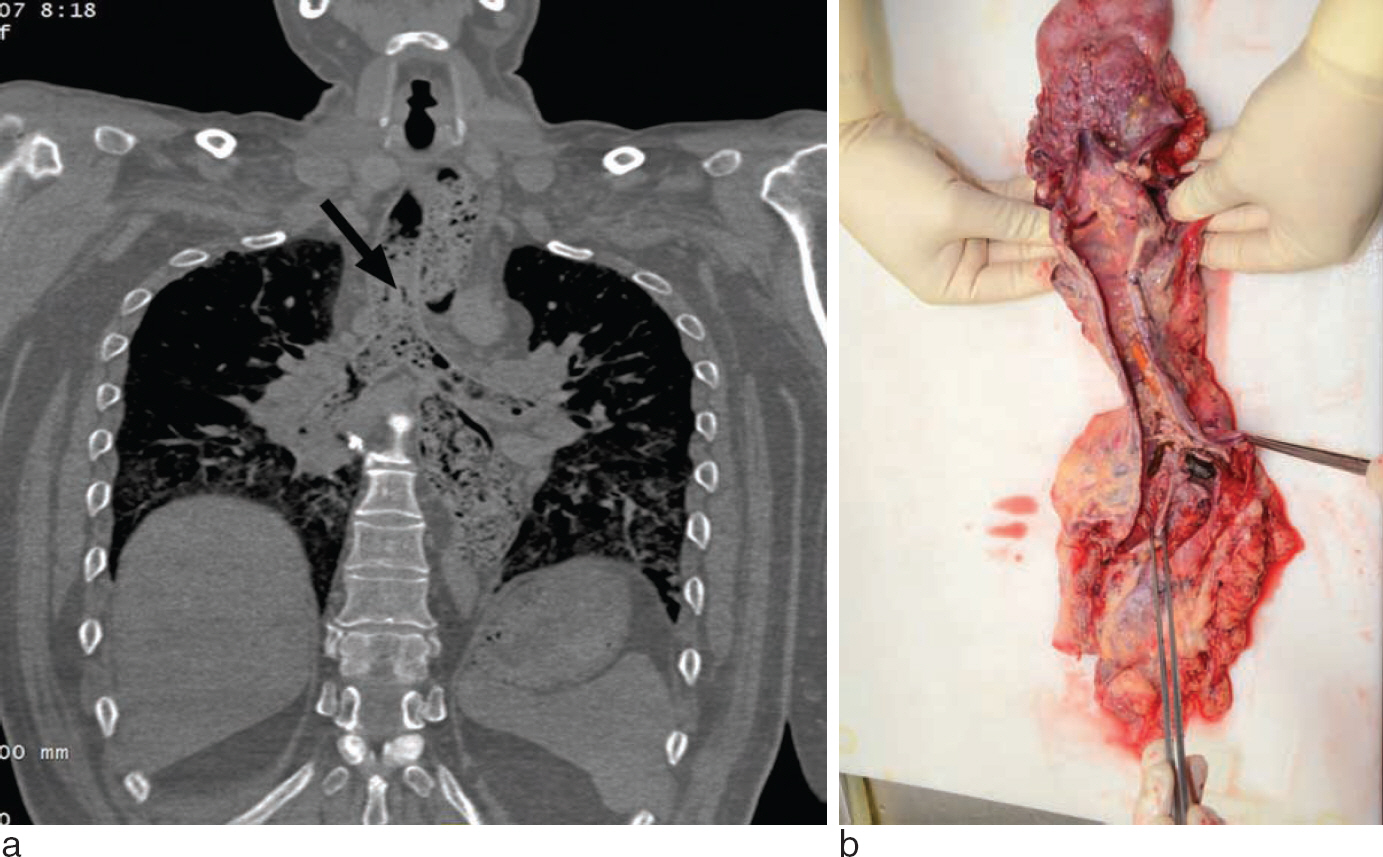

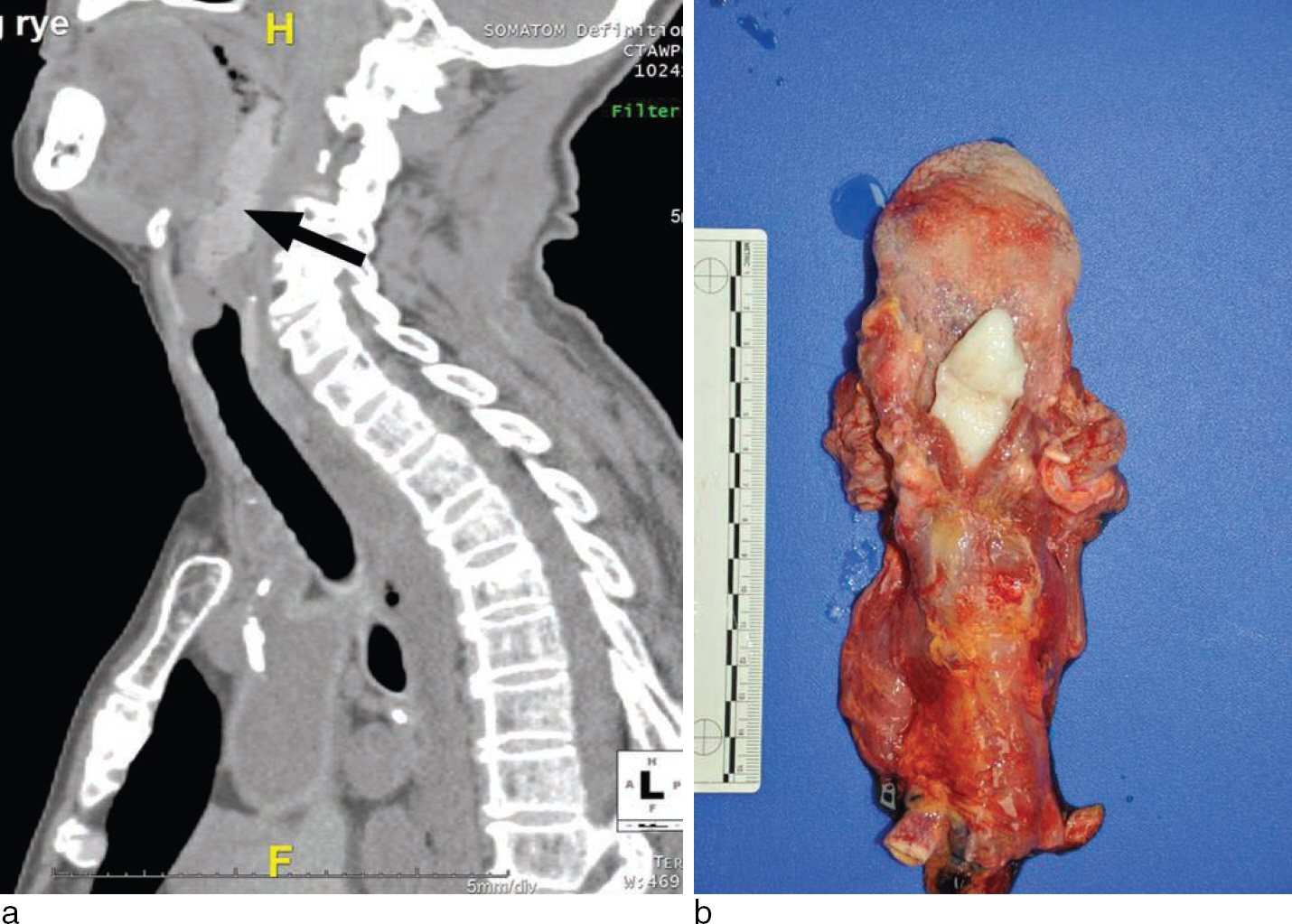

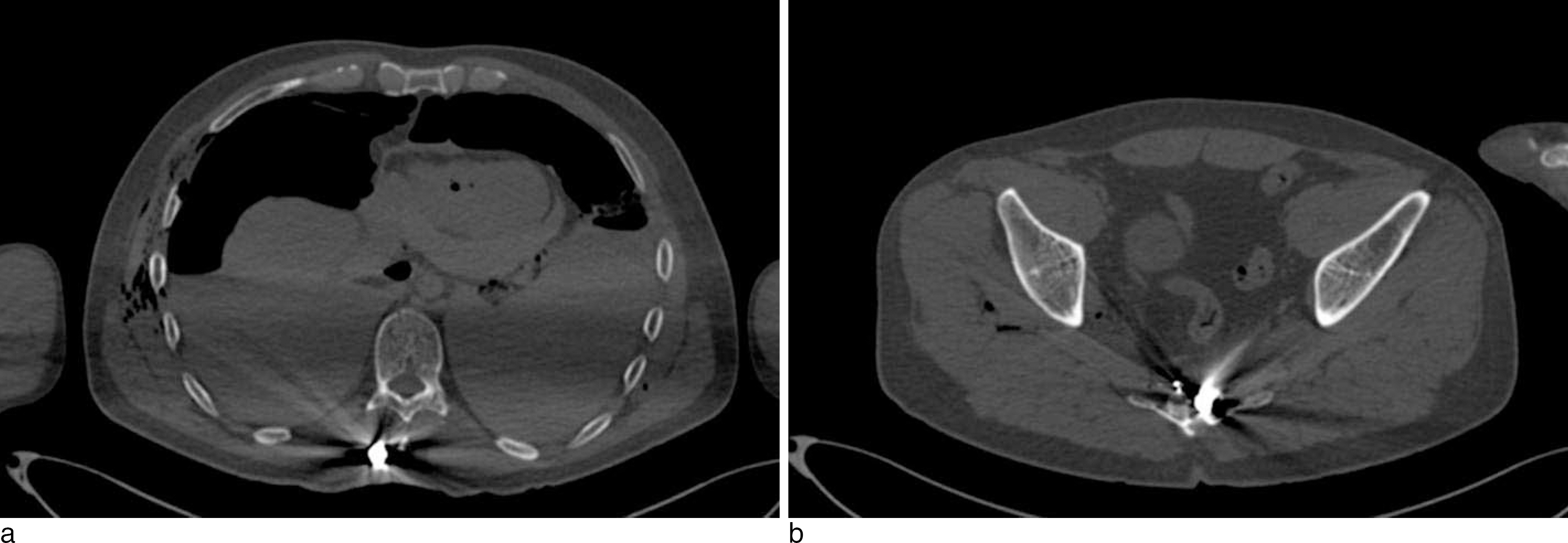

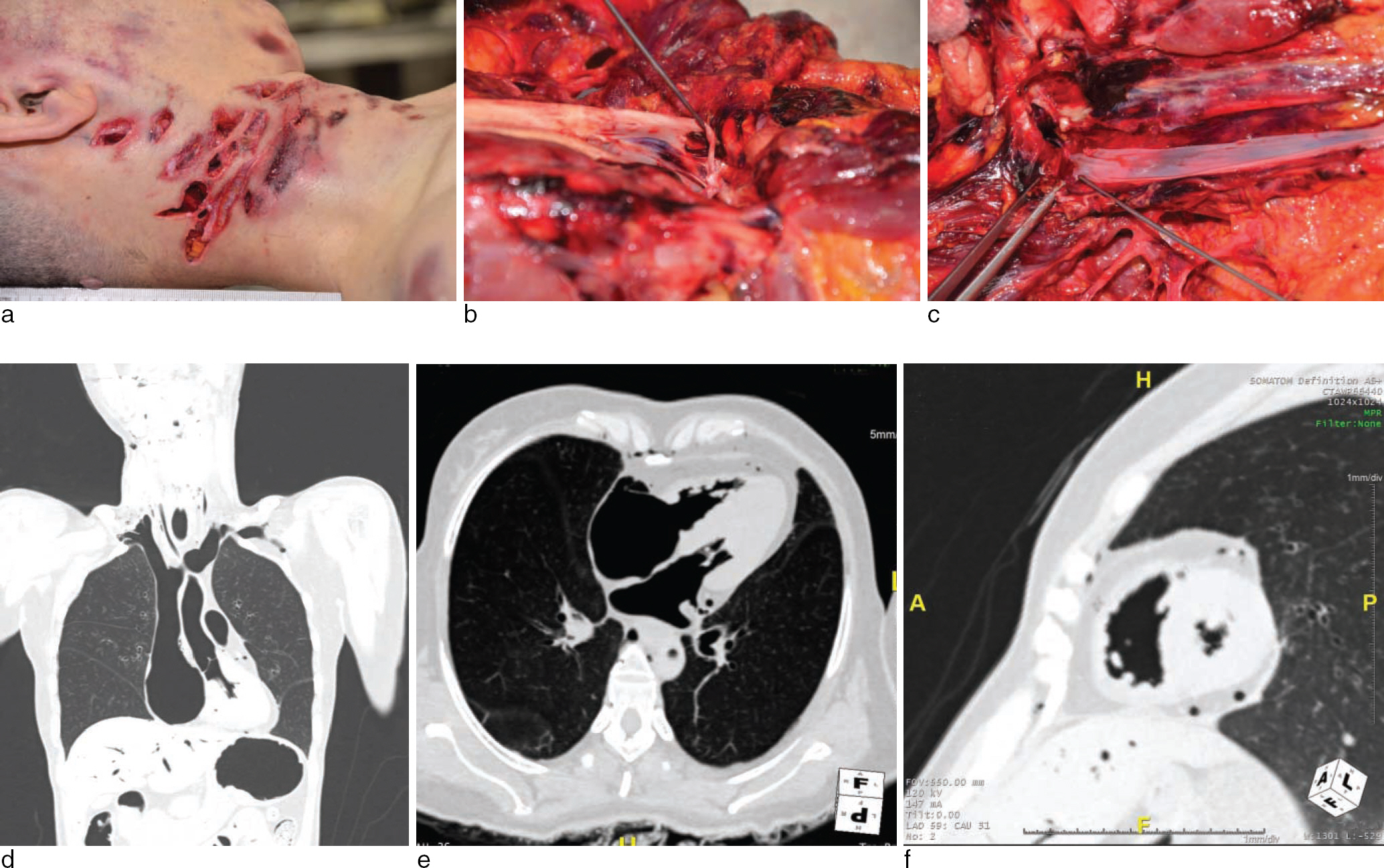

- Despite being a very new field, forensic imaging is rapidly being used in forensic medical practices around the world. Computed tomography images are being produced and used for many reasons. Forensic imaging is being used for preliminary examination of serious findings before a routine autopsy, as it might help to give positive proof in some cases. Some major preliminary findings, such as brain hemorrhage, cardiac tamponade, or aortic dissection, can then be substantiated with the results of the physical autopsy. Forensic imaging techniques may also provide additive evidence about the cause of death such as pneumothorax, ileus, gas embolism, and aspiration that are difficult to detect with the traditional surgical autopsy techniques. Forensic imaging is also proving useful outside the autopsy room; forensic anthropologists and odontologists are using images to help them determine the age, sex, and even lifestyle of human specimens. Finally, forensic images have also begun to function as a form of record keeping in complex cases.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Wu ¨ llenweber R, Schneider V, Grumme T. A computer-to-mographical examination of cranial bullet wounds. Z Rechtsmed. 1977; 80:227–46.2. O'Donnell C, Woodford N. Postmortem radiology – a new subspecialty? Clin Radiol. 2008; 63:1189–94.3. Brogdon BG. Forensic radiology in historical perspective. Thali MJ, Viner M, Brogdon BG, editors. ed.Brogdon's forensic radiology. 2nd ed.Boca Raton: CRC Press;2010. p. 3–7.4. Thali MJ, Jackowski C, Oesterhelweg L, et al. Virtopsy? the Swiss virtual autopsy approach. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2007; 9:100–4.5. Baglivo M, Winklhofer S, Hatch GM, et al. The rise of forensic and postmortem radiology ? analysis of the literature between the year 2000 and 2011. J Forensic Radiol Imaging. 2013; 1:3–9.6. Christe A, Flach P, Ross S, et al. Clinical radiology and postmortem imaging (Virtopsy) are not the same: Specific and unspecific postmortem signs. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2010; 12:215–22.

Article7. Flach PM, Gascho D, Schweitzer W, et al. Imaging in forensic radiology: an illustrated guide for postmortem computed tomography technique and protocols. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014. ;Epub ahead of print.

Article8. Jackowski C, Thali M, Aghayev E, et al. Postmortem imaging of blood and its characteristics using MSCT and MRI. Int J Legal Med. 2006; 120:233–40.

Article9. Andenmatten MA, Thali MJ, Kneubuehl BP, et al. Gunshot injuries detected by postmortem multislice computed tomography (MSCT): a feasibility study. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2008; 10:287–92.

Article10. Kauczor HU, Riepert T, Wolcke B, et al. Fatal venous air embolism: proof and volumetry by helical CT. Eur J Radiol. 1995; 21:155–7.

Article11. Jackowski C, Thali M, Sonnenschein M, et al. Visualization and quantification of air embolism structure by processing postmortem MSCT data. J Forensic Sci. 2004; 49:1339–42.

Article12. Makino Y, Shimofusa R, Hayakawa M, et al. Massive gas embolism revealed by two consecutive postmortem computed-tomography examinations. Forensic Sci Int. 2013; 231:e4–10.

Article13. Estrera AS, Pass LJ, Platt MR. Systemic arterial air embolism in penetrating lung injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990; 50:257–61.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Common Postmortem Computed Tomography Findings Following Atraumatic Death: Differentiation between Normal Postmortem Changes and Pathologic Lesions

- Discrepancies in the Cause and Manner of Death Reported in Postmortem Inspection and Autopsy

- Usefulness of Mast Cell Tryptase Analysis for Postmortem Diagnosis of Anaphylactic Shock

- Differences in the Determination of Cause and Manner of 127 Natural Death Cases by Postmortem Inspection and Autopsy

- Postmortem Diagnosis of Diabetic Ketoacidosis: An Autopsy Case