J Korean Soc Spine Surg.

2015 Mar;22(1):1-7. 10.4184/jkss.2015.22.1.1.

The Prognostic Factors of Neurologic Recovery in Spinal Cord Injury

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, College of Medicine, Dong-A University, Korea. gylee@dau.ac.kr

- KMID: 1800387

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4184/jkss.2015.22.1.1

Abstract

- STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective study.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate and compare the factors affecting recovery of spinal cord injury following cervical and thoracolumbar spine injuries. SUMMARY OF LITERATURE REVIEW: Several authors have reported the factors to predict the prognosis of spinal cord injury, but the objective prognostic factors are still controversial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From June 2006 to March 2013, a total of 44 patients with spinal cord injury were evaluated. Prognostic factors analyzed were sex, age, neurologic status, fracture type, time to operation, use of steroid, and signal change on MRI. We analyzed the relation between each factor and the neurologic recovery. The mean follow-up period was 12 months. The neurologic recovery was analyzed by the ASIA impairment scale at the first and the last neurologic examination.

RESULTS

Among 44 patients, 15 sustained complete cord injury while 29 had incomplete cord injury. Significant neurologic recovery using the ASIA impairment scale was evaluated in the incomplete spinal cord injury group. Among this group, the prognosis for Brown-sequard syndrome is better than for central cord syndrome and anterior cord syndrome. There was no significant difference in other factors (fracture site, time to operation, use of steroid or signal change on MRI).

CONCLUSIONS

The prognosis in spinal cord injury is determined by the initial neurologic damage and neurologic recovery is not related with the fracture type, time to operation, use of steroid and signal change on MRI.

MeSH Terms

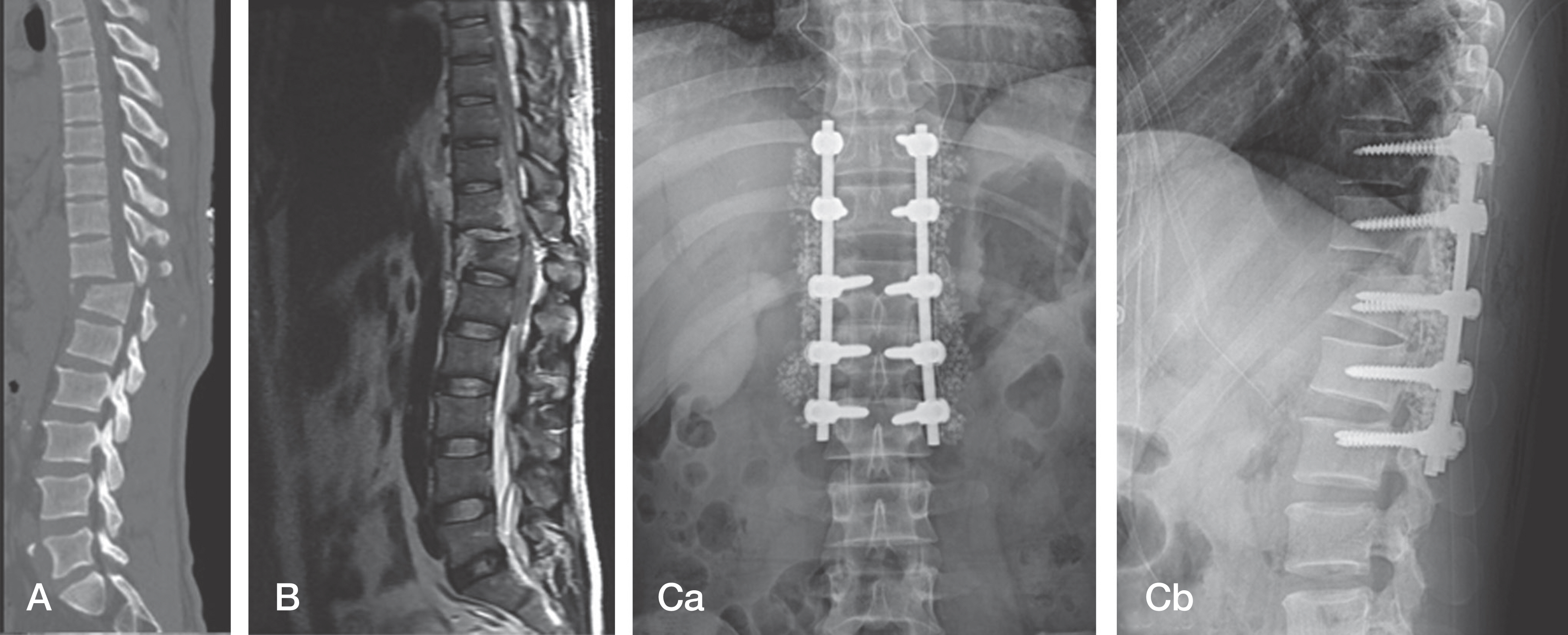

Figure

Reference

-

1. You JW, Sohn HM, Park SH. Diminution of Secondary injury after Administration Pharmacologic Agents in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Rat Model–Comparision of Statins Erythropoietin and Polyethylene Glycol-. J Korean Soc Spine Surg. 2012; 196:77–84.2. Nobunaga AI, Go BK, Karunas RB. Recent demographic and injury trends in people served by the Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999; 80:1372–82.

Article3. Standard for neurologic and functional class of spinal cord injury. Chicago: American Spinal Injury Association;1992.4. Guttmann L, Frankel H. The value of intermittent catheterization in early management of traumatic paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1966; 4:63–84.5. Bosch A, Stauffer ES, Nikel VL. Incomplete traumatic quadriplegia: A ten year review. JAMA. 1971; 216:473–8.6. Lucas JT, ducker TB. Motor classification of spinal cord injuries with mobility, morbidity and recovery indices. Am Surg. 1979; 45:151–8.7. Bedbrook GM. Pathological principles of the management of spinal cord trauma. Paraplegia. 1966; 4:43–56.8. Castellano V, Bocconi FL. Injuries of the cervical spine with spinal cord involvement (myelic fracture): Statistical considerations. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1970; 31:188–94.9. White AA, Southwick WO, Panjabi MM. Clinical instability in the lower cervical spine –a review of past and current concepts. Spine(Phila Pa 1976). 1976; 1:15–27.

Article10. Song KJ, Lee KB. The Prognosis of the Acute Cervical spinal injury. J korea Orthop Assoc. 1998; 33:794–801.11. Cho DY, Seo JG, Baek SN, et al. Surgical Treatment of the Unstable Lower Cervical Spine Injuries. J Korea Orthop Assoc. 1990; 25:151–60.

Article12. Hill SA, Miler CA, Kosnik EJ, et al. Pediatric neck injuries. A clinical study. Neurosrug. 1984; 60:700–6.13. Evans DL, Bethem D. Cervical spine injuries in children. J Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1989; 9:563–8.

Article14. Delamarter RB, Sherman JE, Carr JB. Pathophysilogy of spinal cord injury. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995; 77:1042–9.15. Delamarter RB, Sherman JE, Carr JB. Cauda equine syndrome: neurologic recovery following immediate, early, or late decompression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991; 16:1022–9.16. Schaefer DM, Flanders AE, Northrup BE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of acute spinal trauma: Correlation with severity of neurologic injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988; 14:1090–5.17. Kulkarni MV, McArdle CB, Kopanicky D, et al. Acute spinal cord injury: MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology. 1987; 164:837–43.

Article18. Vellman W, Hawkes AP, Lammertse DP. Administration of corticosteroids for acute spine cord injury: the current practice of trauma medical directors and emergency medical system physician advisors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003; 28:941–7.19. Bracken MB. Methylprednisolone and acute spinal cord injury: an update of the randomized evidence. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26(24 Suppl):S47–54.20. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury: results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J. 1990; 322:1405–11.21. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, et al. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997; 277:1597–604.22. Hulbert RJ, Moulton R. Why do you prescribe meth- ylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury? A Canadian perspective and a position statement. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002; 29:236–9.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Time-course of Neurologic Recovery in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury

- Current Concept and Future of the Management of Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review

- The Prognosis of the Acute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury

- Neurologic Recovery According to Early Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Traumatic Cervical Spinal Cord Injuries

- Nerve injury in an undiagnosed adult tethered cord syndrome patients following spinal anesthesia: A case report