Korean Circ J.

2008 Sep;38(9):483-490. 10.4070/kcj.2008.38.9.483.

Comparison of Primary Prevention Strategies for Coronary Heart Disease in Asymptomatic Individuals: The National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III Guideline Versus the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education Guideline

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hjchang@snu.ac.kr

- 2Division of Cardiology, The Cardiovascular Center, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- 3Division of Radiology, The Cardiovascular Center, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- KMID: 1776349

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2008.38.9.483

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

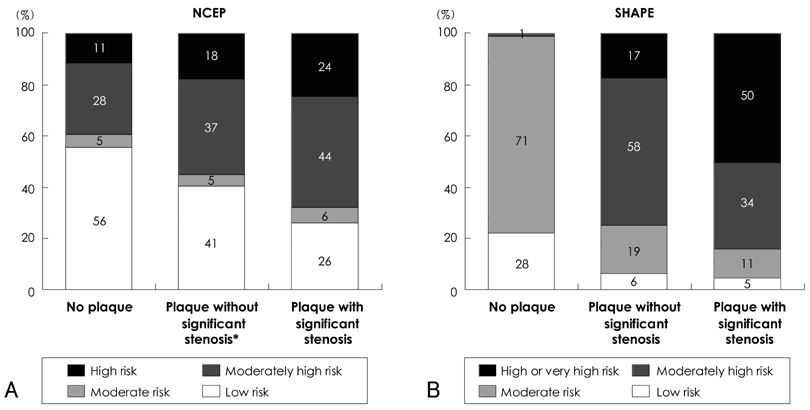

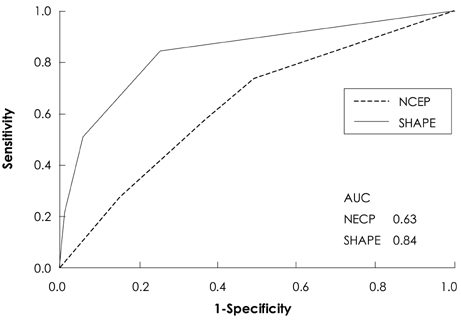

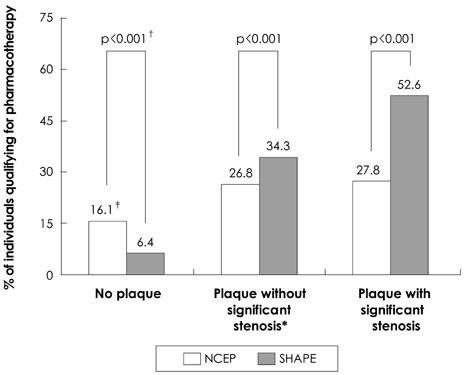

The National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP-ATP) III guideline has been widely accepted for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD). The coronary artery calcium score (CACS) has recently been recognized as an excellent predictor of CHD events, and a primary prevention strategy based on the CACS [the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education (SHAPE) guideline] has been proposed. The purpose of this study was to explore how the guidelines function for asymptomatic South Korean individuals. SUBJECTS AND METHODS: We consecutively enrolled 2,079 asymptomatic subjects (age range for men: 45-75 years, age range for women: 55-75 years) who underwent CACS and coronary CT angiography (CCTA) as a part of a health check-up. We analyzed the differences of the target population for CHD prevention according to the 2 guidelines and we compared them in terms of the presence of occult CHD. RESULTS: Four-hundred eighteen (20%) individuals were recommended for pharmacotherapy according to the NCEP-ATP III and 371 (18%) were recommended for pharmacotherapy according to the SHAPE guideline (Cohen's kappa=0.36). According to the SHAPE guideline, more individuals with significant stenosis noted on the CCTA were categorized into the high or very high risk group (50% vs. 24%, respectively, p<0.001) and recommended for pharmacotherapy (53% vs. 28%%, respectively, p<0.001). However, 57 (43%) individuals with significant stenosis on the CCTA were not suitable for pharmacotherapy according to either the NCEP-ATP III or the SHAPE guideline. CONCLUSION: Comparing the NCEP-ATP III and the SHAPE guidelines, there were considerable differences for primary prevention in the target population. Although SHAPE might provide more accurate stratification in terms of the presence of occult CHD, a more precise risk stratification algorithm needs to be implemented for this population.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Myerburg RJ, Interian A Jr, Mitrani RM, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Frequency of sudden cardiac death and profiles of risk. Am J Cardiol. 1997. 80:10F–19F.2. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002. 106:3143–3421.3. Akosah KO, Schaper A, Cogbill C, Schoenfeld P. Preventing myocardial infarction in the young adult in the first place: how do the National Cholesterol Education Panel III guidelines perform? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. 41:1475–1479.4. Nasir K, Michos ED, Blumenthal RS, Raggi P. Detection of high-risk young adults and women by coronary calcium and National Cholesterol Education Program Panel III guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. 46:1931–1936.5. Brindle P, Beswick A, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Accuracy and impact of risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Heart. 2006. 92:1752–1759.6. Wong ND, Hsu JC, Detrano RC, Diamond G, Eisenberg H, Gardin JM. Coronary artery calcium evaluation by electron beam computed tomography and its relation to new cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2000. 86:495–498.7. Raggi P, Cooil B, Callister TQ. Use of electron beam tomography data to develop models for prediction of hard coronary events. Am Heart J. 2001. 141:375–382.8. Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, Doherty TM, Detrano RC. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2004. 291:210–215.9. Pletcher MJ, Tice JA, Pignone M, Browner WS. Using the coronary artery calcium score to predict coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2004. 164:1285–1292.10. Greenland P, Bonow RO, Brundage BH, et al. ACCF/AHA 2007 clinical expert consensus document on coronary artery calcium scoring by computed tomography in global cardiovascular risk assessment and in evaluation of patients with chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Expert Consensus Task Force (ACCF/AHA Writing Committee to Update the 2000 Expert Consensus Document on Electron Beam Computed Tomography) developed in collaboration with the Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:378–402.11. Kim KS. Imaging markers of subclinical atherosclerosis. Korean Circ J. 2007. 37:1–8.12. Naghavi M, Falk E, Hecht HS, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: part III. executive summary of the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education (SHAPE) Task Force report. Am J Cardiol. 2006. 98:2H–15H.13. Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification. Circulation. 2005. 111:1313–1320.14. Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990. 15:827–832.15. Oh HJ, Kwon K, Park SH, et al. CT coronary angiography using multidetector computed tomography in coronary artery disease: a comparative study to quantitative coronary angiography. Korean Circ J. 2004. 34:1167–1173.16. Leber AW, Becker A, Knez A, et al. Accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography to classify and quantify plaque volumes in the proximal coronary system: a comparative study using intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 47:672–677.17. Gilard M, Le Gal G, Cornily JC, et al. Midterm prognosis of patients with suspected coronary artery disease and normal multislice computed tomographic findings: a prospective management outcome study. Arch Intern Med. 2007. 167:1686–1689.18. Pundziute G, Schuijf JD, Jukema JW, et al. Prognostic value of multislice computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:62–70.19. Friesinger GC, Page EE, Ross RS. Prognostic significance of coronary arteriography. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1970. 83:78–92.20. Jones WB, Riley CP, Reeves TJ, Sheffield LT. Natural history of coronary artery disease. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1972. 48:1109–1125.21. Bruschke AV, Proudfit WL, Sones FM Jr. Progress study of 590 consecutive nonsurgical cases of coronary disease followed 5-9 years: II. ventriculographic and other correlations. Circulation. 1973. 47:1154–1163.22. Brindle P, Emberson J, Lampe F, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Framingham coronary risk score in British men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003. 327:1267.23. Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hadamitzky M, Kastrati A, Martinoff S, Schomig A. Prevalence of noncalcified coronary plaques by 64-slice computed tomography in patients with an intermediate risk for significant coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 48:312–318.24. Cheng VY, Lepor NE, Madyoon H, Eshaghian S, Naraghi AL, Shah PK. Presence and severity of noncalcified coronary plaque on 64-slice computed tomographic coronary angiography in patients with zero and low coronary artery calcium. Am J Cardiol. 2007. 99:1183–1186.25. Choe KO, Kim MJ, Choi BW, et al. Distribution of coronary calcium score in healthy middle-aged Korean. J Korean Radiol Soc. 1999. 41:885–891.26. Kim D, Choi SY, Choi EK, et al. Distribution of coronary artery calcification in an asymptomatic Korean population: association with risk factors of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. Koeran Circ J. 2008. 38:29–35.27. Einstein AJ, Henzlova MJ, Rajagopalan S. Estimating risk of cancer associated with radiation exposure from 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. JAMA. 2007. 298:317–323.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- New Strategy in the Management of Hypercholesterolemia: Based on National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III

- Reconsideration for current guideline of lipid-lowering therapy in patients with coronary artery disease

- Risk Factors and Primary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease

- Factors Affecting the Difference between the Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Concentrations Measured Directly and Calculated Using the Friedewald Formula

- How Much to Lower Serum LDL-Cholesterol for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease?