Cancer Res Treat.

2023 Apr;55(2):408-418. 10.4143/crt.2022.126.

Trends and Patterns of Cancer Burdens by Region and Income Level in Korea: A National Representative Big Data Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Institute for Future Public Health, Graduate School of Public Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2541228

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2022.126

Abstract

- Purpose

This study aimed to elucidate the trends and characteristics of the cancer burden in Korea by cancer site, region, and income level.

Materials and Methods

Korean National Burden of Disease research methodology was applied to measure the cancer burden in Korea from 2008 to 2018. The cause of death and national health insurance claims data were obtained from Statistics Korea and the National Health Insurance Service, respectively. An incidence-based approach was applied to calculate the disability-adjusted life-years, which is a summary measure of population health.

Results

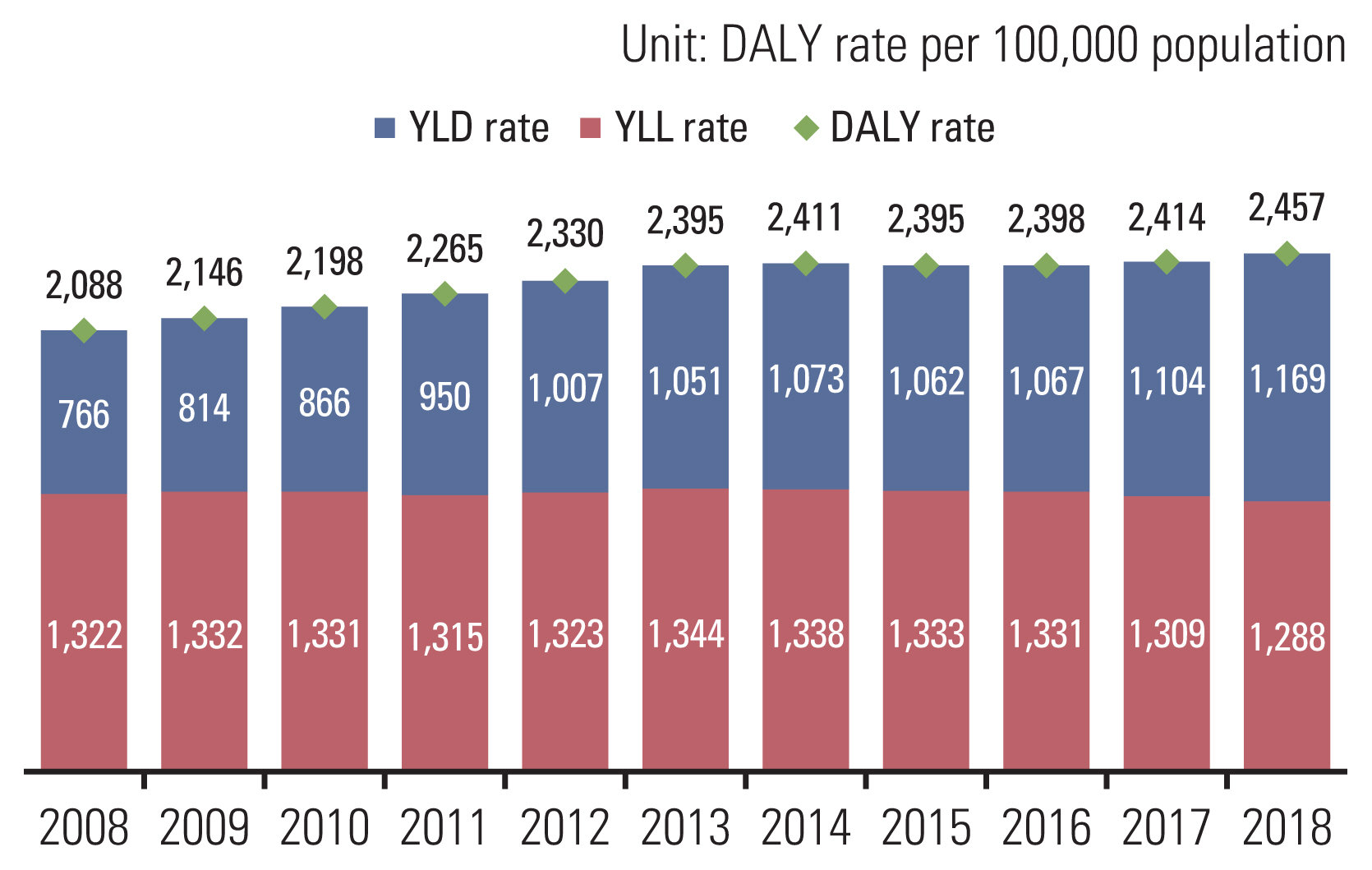

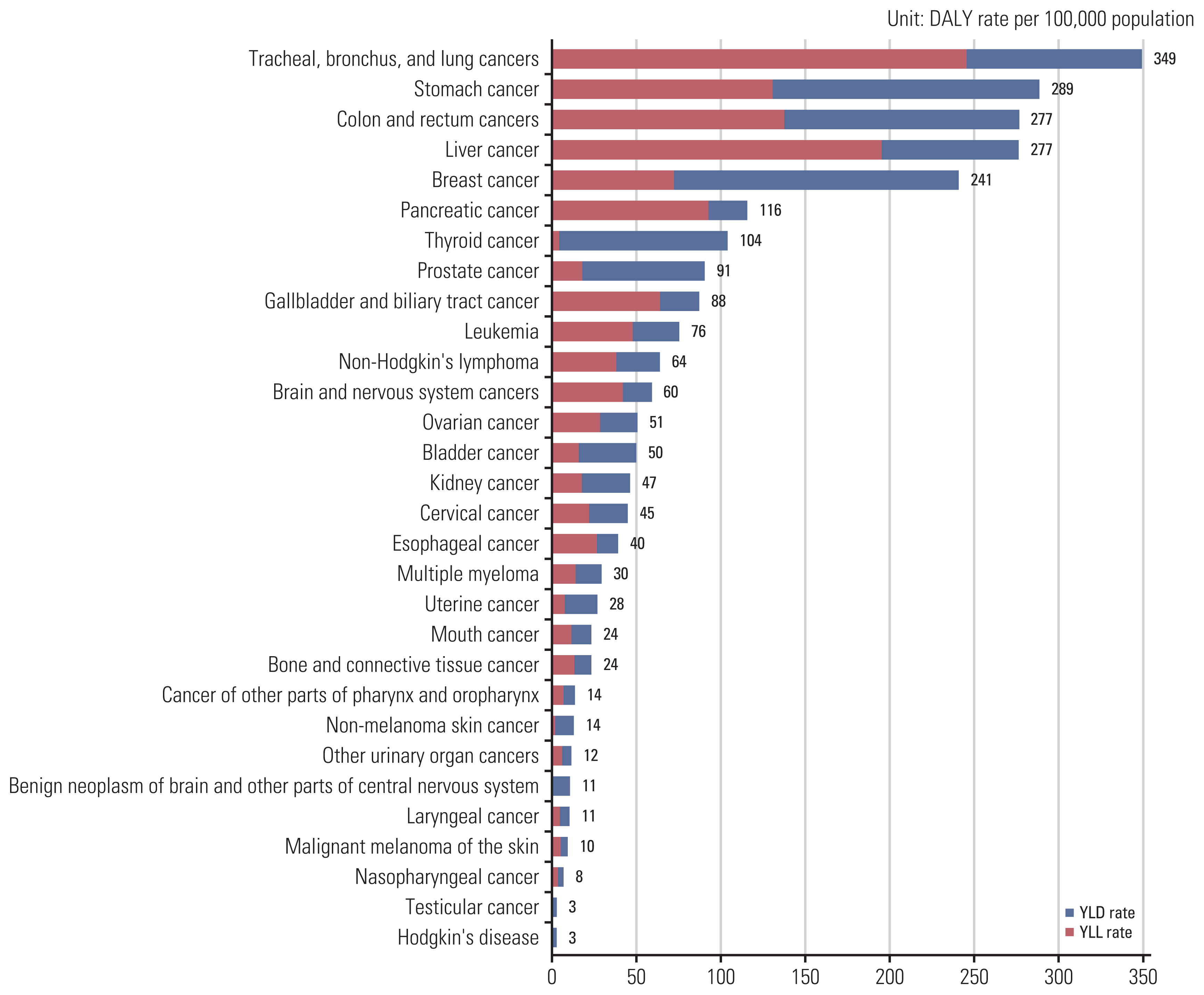

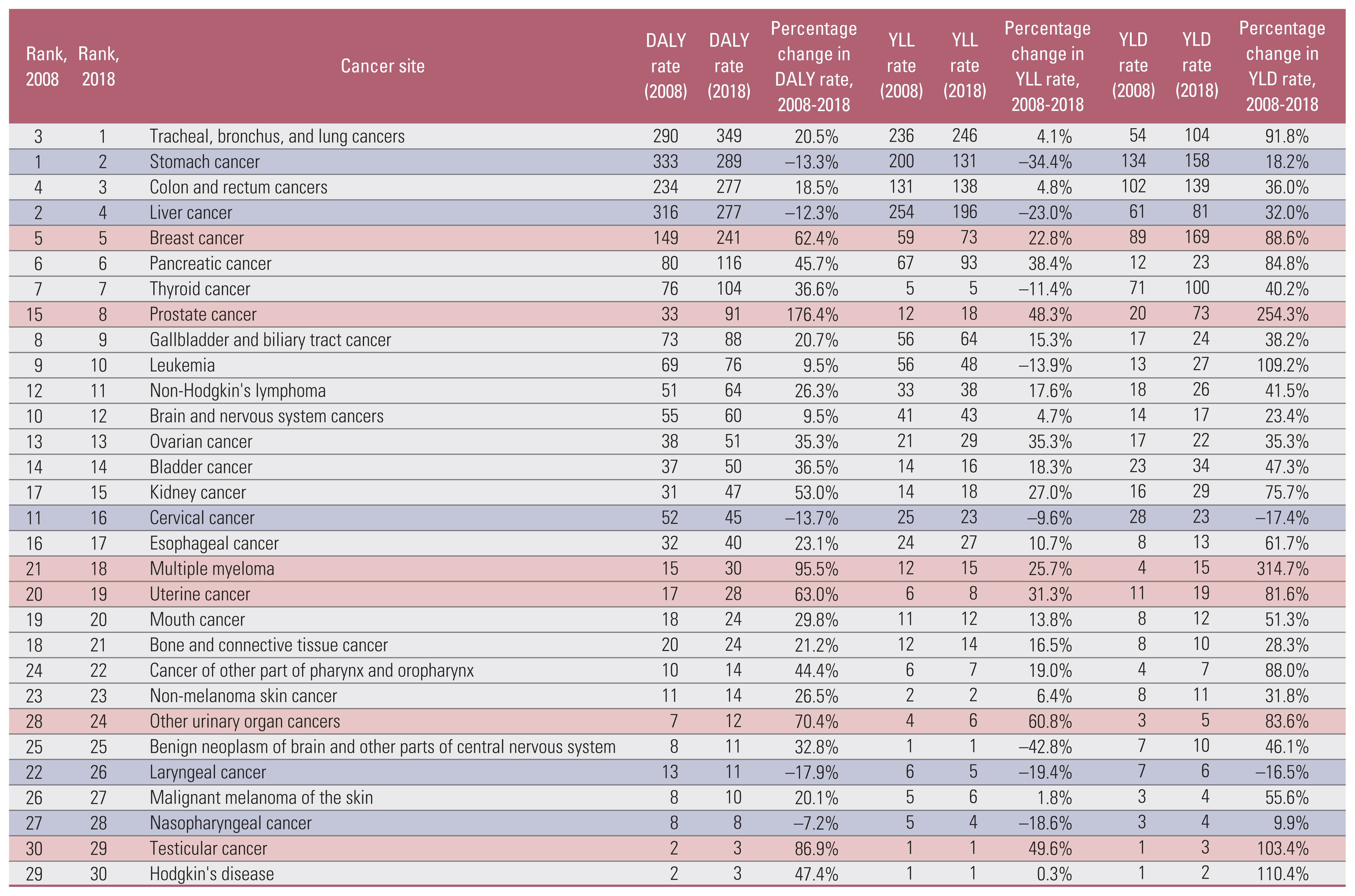

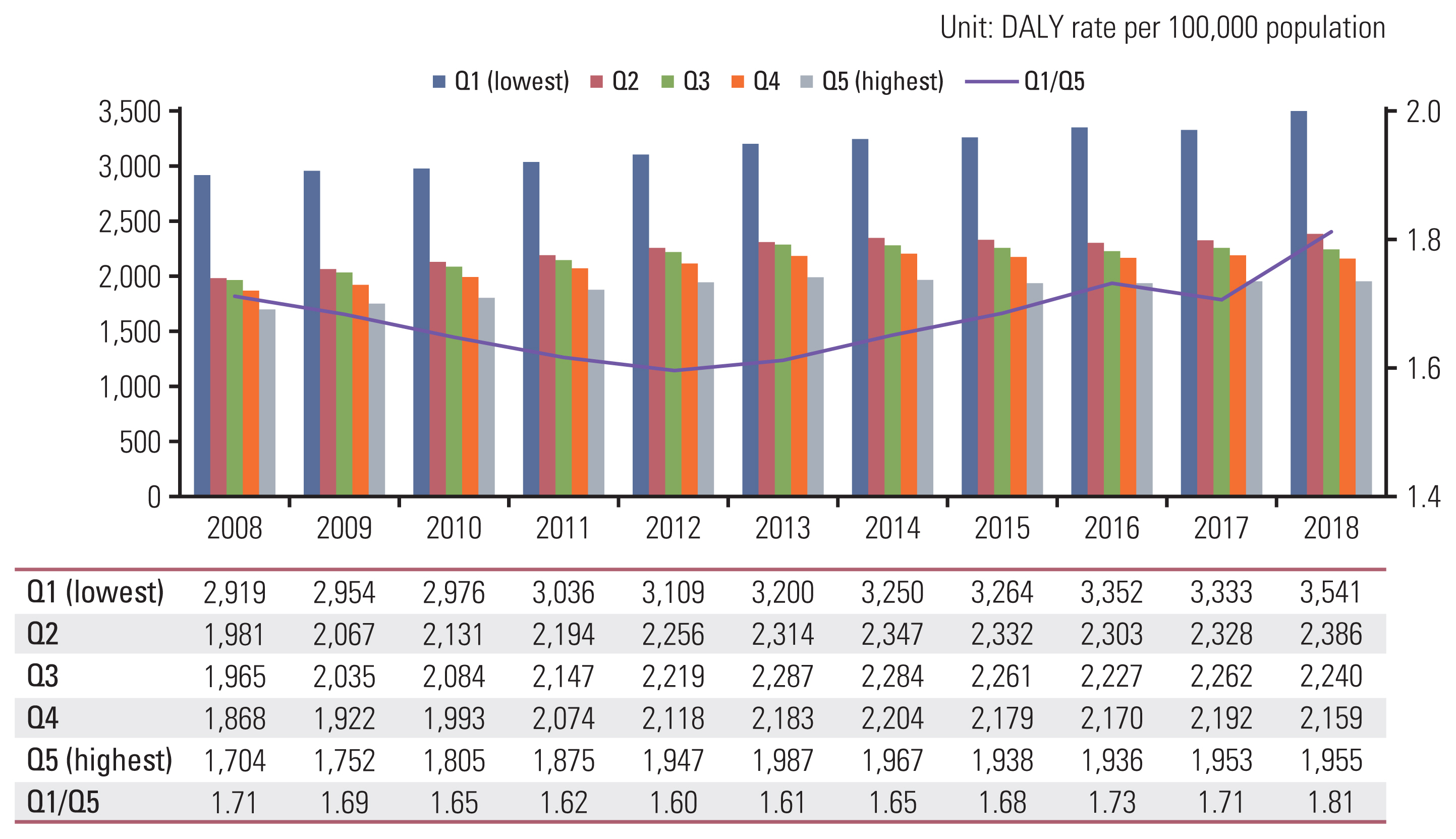

In the past decade, the cancer burden in Korea increased from 2,088 to 2,457 person-years per 100,000 population. Among the cancer burden, the years of life lost decreased, and the years lived with disabilities increased. Cancers of the trachea, bronchus, and lung had the highest disease burden, followed by those of the stomach, colon and rectum, liver, and breast.

Conclusion

The findings of this study can provide valuable quantitative data for prioritizing and evaluating cancer prevention strategies and implementing cancer policies. Estimating the difference in cancer burden according to region and income level within a country can yield useful data to understand the nature of the cancer burden and scale of the problem. In addition, the results of this study provide a better understanding of the causes of cancer patterns, thereby generating new hypotheses regarding its pathogenesis.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68:394–424.

Article2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209–49.

Article3. Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2018. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2020.4. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat. 2019; 51:417–30.

Article5. Lin L, Li Z, Yan L, Liu Y, Yang H, Li H. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence and death for 29 cancer groups in 2019 and trends analysis of the global cancer burden, 1990–2019. J Hematol Oncol. 2021; 14:197.

Article6. GBD Diseases Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396:1204–22.7. Jung YS, Kim YE, Park H, Oh IH, Jo MW, Ock M, et al. Measuring the burden of disease in Korea, 2008–2018. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021; 54:293–300.

Article8. Shin YS, Yoon SJ, Park HJ. The method for burden of disease: for evidence based health policy making. Seoul: Kyungmunsa;2004.

Article9. Lee YR, Kim YA, Park SY, Oh CM, Kim YE, Oh IH. Application of a modified garbage code algorithm to estimate cause-specific mortality and years of life lost in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(Suppl 2):S121–8.

Article10. Statistics Korea. Life tables [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2022. [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B42&conn_path=I3 .11. Yang MS, Park M, Back JH, Lee GH, Shin JH, Kim K, et al. Validation of cancer diagnosis based on the National Health Insurance Service Database versus the National Cancer Registry Database in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2022; 54:352–61.

Article12. National Health Insurance Service. National Health Insurance statistical yearbook, 2020. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;2021.13. National Health Insurance Sharing Service. Data provision guide [Internet]. Wonju: National Health Insurance Sharing Service;c2019. [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ay/bdaya001iv.do .14. Kim YE, Jo MW, Park H, Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Pyo J, et al. Updating disability weights for measurement of healthy life expectancy and disability-adjusted life year in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e219.

Article15. Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H, McCormack V, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8:e1027–37.

Article16. Kang SY, Kim YS, Kim Z, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Park S, et al. Breast cancer statistics in Korea in 2017: data from a breast cancer registry. J Breast Cancer. 2020; 23:115–28.

Article17. Norsa’adah B, Rusli BN, Imran AK, Naing I, Winn T. Risk factors of breast cancer in women in Kelantan, Malaysia. Singapore Med J. 2005; 46:698–705.18. Tolessa L, Sendo EG, Dinegde NG, Desalew A. Risk factors associated with breast cancer among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study. Int J Womens Health. 2021; 13:101–10.

Article19. Ghiasvand R, Bahmanyar S, Zendehdel K, Tahmasebi S, Talei A, Adami HO, et al. Postmenopausal breast cancer in Iran: risk factors and their population attributable fractions. BMC Cancer. 2012; 12:414.

Article20. Hong S, Won YJ, Lee JJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Im JS, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2018. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:301–15.

Article21. National Cancer Center. National Cancer Screening Program [Internet]. Goyang: National Cancer Center;2022. [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.ncc.re.kr/main.ncc?uri=eng-lish/sub04_ControlPrograms03 .22. Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Korea health statistics 2020. Cheongju: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2022.23. Min KJ, Suh DH, Baba T, Chen X, Kim JW, Kobayashi Y, et al. Time for enhancing government-led primary prevention of cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2021; 32:e12.

Article24. Landy R, Pesola F, Castanon A, Sasieni P. Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2016; 115:1140–6.

Article25. Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Suh M, Park B, Song SH, et al. Effectiveness of the Korean National Cancer Screening Program in reducing gastric cancer mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017; 152:1319–28.

Article26. Hashim D, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C, Rota M, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, et al. The global decrease in cancer mortality: trends and disparities. Ann Oncol. 2016; 27:926–33.

Article27. Lortet-Tieulent J, Soerjomataram I, Lin CC, Coebergh JW, Jemal A. U.S. burden of cancer by race and ethnicity according to disability-adjusted life years. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51:673–81.

Article28. Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010; 36:349–70.

Article29. Louwman WJ, Aarts MJ, Houterman S, van Lenthe FJ, Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML. A 50% higher prevalence of life-shortening chronic conditions among cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Br J Cancer. 2010; 103:1742–8.

Article30. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation;2018.31. Kang HY, Kim I, Kim YY, Bahk J, Khang YH. Income differences in screening, incidence, postoperative complications, and mortality of thyroid cancer in South Korea: a national population-based time trend study. BMC Cancer. 2020; 20:1096.

Article32. Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Welch HG. Korea’s thyroid-cancer “epidemic”: screening and overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:1765–7.

Article33. Cheng I, Witte JS, McClure LA, Shema SJ, Cockburn MG, John EM, et al. Socioeconomic status and prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates among the diverse population of California. Cancer Causes Control. 2009; 20:1431–40.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Trends in Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) and Disparities by Income and Region in Korea (2008–2020): Analysis of a Nationwide Claims Database

- Measuring the Burden of Disease in Korea Using Disability-Adjusted Life Years (2008–2020)

- Current Trends of Big Data Research Using the Korean National Health Information Database

- Pediatric Cancer Research using Healthcare Big Data

- Analysis of Food Consumption Patterns by Income Levels Using Annual Report on the Family Income and Expenditure Survey