Korean Circ J.

2023 Feb;53(2):69-91. 10.4070/kcj.2022.0255.

Advancing Cardio-Oncology in Asia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic Rochester, Rochester, MN, USA

- 2Department of Cardiology, National Heart Centre Singapore, Singapore

- 3Department of Cardiology, National University Heart Centre Singapore, Singapore

- 4Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

- 5Department of Cardiology, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, Seoul, Korea

- 6Onco-Cardiology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Saitama Cancer Center, Saitama, Japan

- 7Department of Cardiology, Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

- 8Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chi-Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan

- 9Department of Cardiology, St. Luke’s Medical Center, Quezon, The Philippines

- 10Department of Cardiology, Cardinal Santos Medical Center, Metro Manila, The Philippines

- 11Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia

- 12Department of Medical Oncology and Haemato-Oncology, Narayana Superspeciality Hospital and Cancer Institute, Howrah, India

- 13Department of Cardiology, National Heart Institute, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 14Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic Research Institute for Intractable Cardiovascular Disease, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 15Department of Cardiology, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

- KMID: 2539485

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2022.0255

Abstract

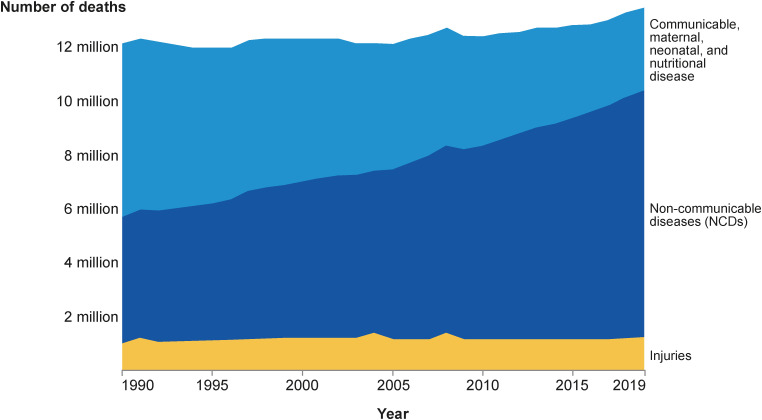

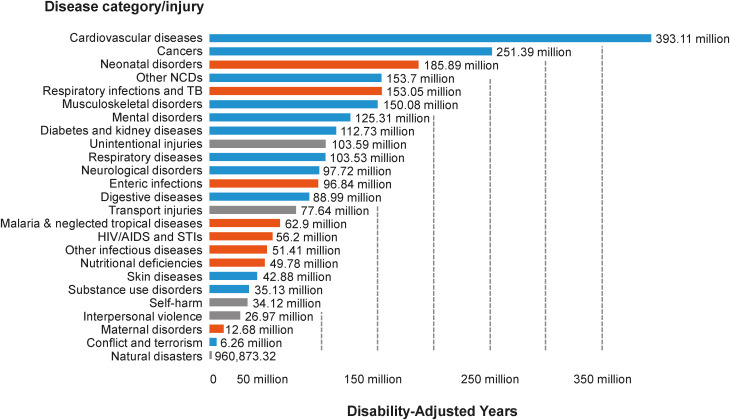

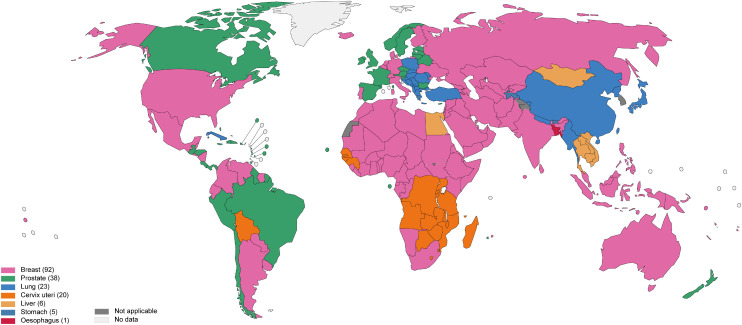

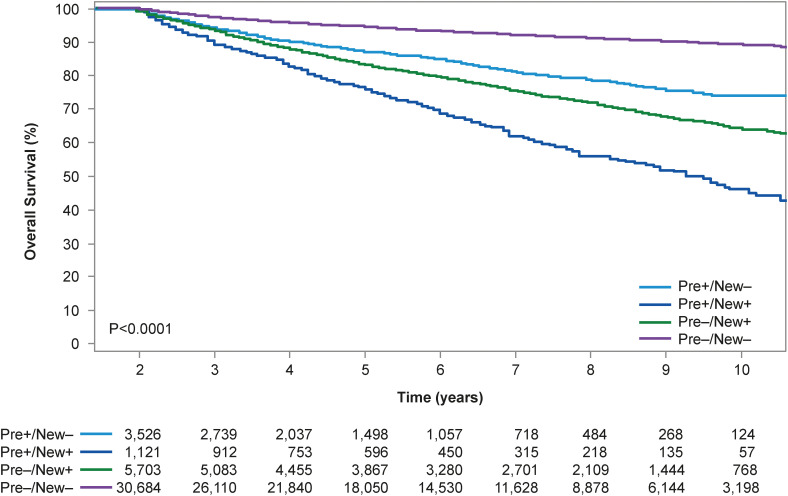

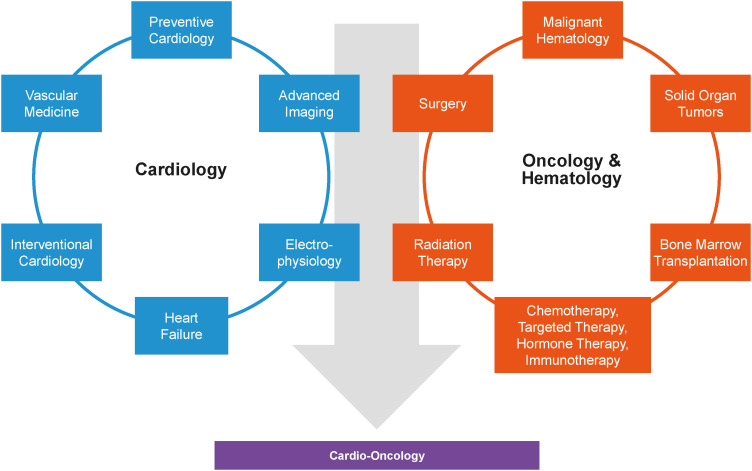

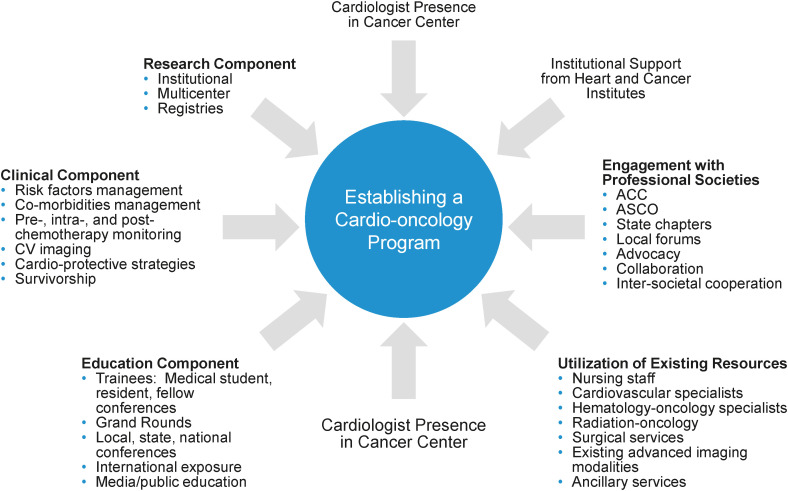

- Cardio-oncology is an emerging multi-disciplinary field, which aims to reduce morbidity and mortality of cancer patients by preventing and managing cancer treatment-related cardiovascular toxicities. With the exponential growth in cancer and cardiovascular diseases in Asia, there is an emerging need for cardio-oncology awareness among physicians and country-specific cardio-oncology initiatives. In this state-of-the-art review, we sought to describe the burden of cancer and cardiovascular disease in Asia, a region with rich cultural and socio-economic diversity. From describing the uniqueness and challenges (such as socio-economic disparity, ethnical and racial diversity, and limited training opportunities) in establishing cardio-oncology in Asia, and outlining ways to overcome any barriers, this article aims to help advance the field of cardio-oncology in Asia.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Falzone L, Salomone S, Libra M. Evolution of cancer pharmacological treatments at the turn of the third millennium. Front Pharmacol. 2018; 9:1300. PMID: 30483135.2. Alvarez-Cardona JA, Ray J, Carver J, et al. Cardio-oncology education and training: JACC Council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:2267–2281. PMID: 33153587.3. Shi S, Lv J, Chai R, et al. Opportunities and challenges in cardio-oncology: a bibliometric analysis from 2010 to 2022. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022; 101227. PMID: 35500730.4. Ritchie H, Spooner F, Roser M. Causes of death [Internet]. place unknown: Our World in Data;2018. cited 2022 August 5. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death.5. Zhao D. Epidemiological features of cardiovascular disease in Asia. JACC Asia. 2021; 1:1–13. PMID: 36338365.6. Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration. Kocarnik JM, Compton K, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022; 8:420–444. PMID: 34967848.7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. About multiple cause of death, 1999–2020. CDC WONDER Online Database website [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2022. cited 2022 February 21. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/.8. Ng CJ, Teo CH, Abdullah N, Tan WP, Tan HM. Relationships between cancer pattern, country income and geographical region in Asia. BMC Cancer. 2015; 15:613. PMID: 26335225.9. World Health Organization. Global health estimates: life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2022. cited 2022 February 8. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates.10. Cao M, Li H, Sun D, Chen W. Cancer burden of major cancers in China: a need for sustainable actions. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020; 40:205–210. PMID: 32359212.11. Liu Y, Zhang YL, Liu JW, Fang FQ, Li JM, Xia YL. Emergence, development, and future of cardio-oncology in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018; 131:2640–2644. PMID: 30381608.12. Oka T, Akazawa H, Sase K, Hatake K, Komuro I. Cardio-oncology in Japan. JACC CardioOncol. 2020; 2:815–818. PMID: 34396300.13. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209–249. PMID: 33538338.14. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022; 72:7–33. PMID: 35020204.15. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute;2022. cited 2022 July 21. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov.16. American Cancer Society. The Cancer Atlas [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society;2022. cited 2022 July 11. Available from: https://canceratlas.cancer.org.17. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Website of IHME [Internet]. Seattle (WA): Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation;2022. cited 2022 July 7. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org.18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Leading causes of death [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2022. cited 2022 July 29. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm.19. Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer;2020. cited 2022 August 10. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.20. Kimura T. East meets West: ethnic differences in prostate cancer epidemiology between East Asians and Caucasians. Chin J Cancer. 2012; 31:421–429. PMID: 22085526.21. Gilchrist SC, Barac A, Ades PA, et al. Cardio-oncology rehabilitation to manage cardiovascular outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019; 139:e997–1012. PMID: 30955352.22. Kwan ML, Cheng RK, Iribarren C, et al. Risk of heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022; 193:669–675. PMID: 35429322.23. Paterson DI, Wiebe N, Cheung WY, et al. Incident cardiovascular disease among adults with cancer: a population-based cohort study. JACC CardioOncol. 2022; 4:85–94. PMID: 35492824.24. Youn JC, Chung WB, Ezekowitz JA, et al. Cardiovascular disease burden in adult patients with cancer: an 11-year nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2020; 317:167–173. PMID: 32360647.25. Strongman H, Gadd S, Matthews AA, et al. Does cardiovascular mortality overtake cancer mortality during cancer survivorship?: an English retrospective cohort study. JACC CardioOncol. 2022; 4:113–123. PMID: 35492818.26. Agarwala V, Choudhary N, Gupta S. A risk-benefit assessment approach to selection of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with early breast cancer: a mini review. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017; 38:526–534. PMID: 29333024.27. Okura Y, Takayama T, Ozaki K, et al. Future projection of cancer patients with cardiovascular disease in Japan by the year 2039: a pilot study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019; 24:983–994. PMID: 30903421.28. Chongsuvivatwong V, Phua KH, Yap MT, et al. Health and health-care systems in southeast Asia: diversity and transitions. Lancet. 2011; 377:429–437. PMID: 21269685.29. The World Bank. World Bank open data [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank;2022. cited 2022 July 29. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/.30. Rahman MM, Karan A, Rahman MS, et al. Progress toward universal health coverage: a comparative analysis in 5 South Asian countries. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177:1297–1305. PMID: 28759681.31. Ohman RE, Yang EH, Abel ML. Inequity in cardio-oncology: identifying disparities in cardiotoxicity and links to cardiac and cancer outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021; 10:e023852. PMID: 34913366.32. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Inequality in Asia and the Pacific [Internet]. Bangkok: Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific;2022. cited 2022 July 11. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/01ExecutiveSummary.pdf .33. Eniu A, Cherny NI, Bertram M, et al. Cancer medicines in Asia and Asia-Pacific: what is available, and is it effective enough? ESMO Open. 2019; 4:e000483. PMID: 31423334.34. Goh BC, Lim JF. Cancer drugs in Asian populations: availability, accessibility, and affordability. Cancer J. 2020; 26:323–329. PMID: 32732675.35. Leighl NB, Nirmalakumar S, Ezeife DA, Gyawali B. An arm and a leg: the rising cost of cancer drugs and impact on access. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2021; 41:1–12.36. IQVIA Institute. Global Oncology Trends 2022. Durham (NC): IQVIA Institute;2022.37. Kimman M, Jan S, Yip CH, et al. ACTION Study Group. Catastrophic health expenditure and 12-month mortality associated with cancer in Southeast Asia: results from a longitudinal study in eight countries. BMC Med. 2015; 13:190. PMID: 26282128.38. Venkatakrishnan K, Burgess C, Gupta N, et al. Toward optimum benefit-risk and reduced access lag for cancer drugs in Asia: a global development framework guided by clinical pharmacology principles. Clin Transl Sci. 2016; 9:9–22. PMID: 26836226.39. Frankart AJ, Nagarajan R, Pater L. The impact of proton therapy on cardiotoxicity following radiation treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021; 51:877–883. PMID: 33033980.40. Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation. 2006; 113:e924–e929. PMID: 16801466.41. Kario K, Chen CH, Park S, et al. Consensus document on improving hypertension management in Asian patients, taking into account Asian characteristics. Hypertension. 2018; 71:375–382. PMID: 29311253.42. Telli ML, Chang ET, Kurian AW, et al. Asian ethnicity and breast cancer subtypes: a study from the California Cancer Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011; 127:471–478. PMID: 20957431.43. Zhou W, Christiani DC. East meets West: ethnic differences in epidemiology and clinical behaviors of lung cancer between East Asians and Caucasians. Chin J Cancer. 2011; 30:287–292. PMID: 21527061.44. O’Donnell PH, Dolan ME. Cancer pharmacoethnicity: ethnic differences in susceptibility to the effects of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009; 15:4806–4814. PMID: 19622575.45. Hao W, Shi YY, Qin YN, et al. Cardioprotective effect of Chinese herbal medicine for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022; 101:e29691. PMID: 35905252.46. Cheng RK. Developing a cardio-oncology program from an early career perspective: challenges faced and lessons learned [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: American College of Cardiology;2018. cited 2022 September 1. Available from: https://www.acc.org/membership/sections-and-councils/imaging-section/section-updates/2018/01/03/22/05/developing-a-cardio-oncology-program-from-an-early-career-perspective-challenges-faced-and-lessons-learned.47. Bhatia N, Lenihan D, Sawyer DB, Lenneman CG. Getting the SCOOP-survey of cardiovascular outcomes from oncology patients during survivorship. Am J Med Sci. 2016; 351:570–575. PMID: 27238918.48. Herrmann J, Loprinzi C, Ruddy K. Building a cardio-onco-hematology program. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018; 20:81. PMID: 30203261.49. Chang WT, Feng YH, Kuo YH, et al. The impact of a multidisciplinary cardio-oncology programme on cardiovascular outcomes in Taiwan. ESC Heart Fail. 2020; 7:2135–2139. PMID: 32621792.50. Pareek N, Cevallos J, Moliner P, et al. Activity and outcomes of a cardio-oncology service in the United Kingdom-a five-year experience. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018; 20:1721–1731. PMID: 30191649.51. International Cardio-Oncology Society. IC-OS Centers of excellence certification [Internet]. Tampa (FL): International Cardio-Oncology Society;2022. cited 2022 August 20. Available from: https://ic-os.org/excellence-certification/.52. Lyon AR, Dent S, Stanway S, et al. Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment in cancer patients scheduled to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapies: a position statement and new risk assessment tools from the Cardio-Oncology Study Group of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the International Cardio-Oncology Society. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020; 22:1945–1960. PMID: 32463967.53. Hayek SS, Ganatra S, Lenneman C, et al. Preparing the cardiovascular workforce to care for oncology patients: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:2226–2235. PMID: 31047011.54. Peng J, Rushton M, Johnson C, et al. An international survey of healthcare providers’ knowledge of cardiac complications of cancer treatments. Cardiooncology. 2019; 5:12. PMID: 32154018.55. Xia Y, Liu J. Working together to advance cardio-oncology in China. JACC CardioOncol. 2020; 2:144–145. PMID: 34396222.56. Kim H, Chung WB, Cho KI, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cardiovascular toxicity related to anti-cancer treatment in clinical practice: an opinion paper from the Working Group on Cardio-Oncology of the Korean Society of Echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2018; 26:1–25. PMID: 29629020.57. Bhatt DL. Birth and maturation of cardio-oncology. JACC CardioOncol. 2019; 1:114–116. PMID: 34396168.58. Yoon GJ, Telli ML, Kao DP, Matsuda KY, Carlson RW, Witteles RM. Left ventricular dysfunction in patients receiving cardiotoxic cancer therapies are clinicians responding optimally? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:1644–1650. PMID: 21050974.59. Oren O, Neilan TG, Fradley MG, Bhatt DL. Cardiovascular safety assessment in cancer drug development. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021; 10:e024033. PMID: 34913360.60. McCain K, Hardesty C, Wong A. Charting a course to remodel universal healthcare in the Asia-Pacific [Internet]. Cologny: World Economic Forum;2021. cited 2022 July 16. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/how-to-remodel-universal-healthcare-in-the-asia-pacific/.61. Khalid A. Expanding universal health coverage in Asia [Internet]. Tacoma (WA): The Borgen Project;2015. cited 2022 August 25. Available from: https://borgenproject.org/universal-health-care-in-asia/.62. Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, Muga R, Otoo N. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet. 2012; 380:933–943. PMID: 22959390.63. Addison D, Campbell CM, Guha A, Ghosh AK, Dent SF, Jneid H. Cardio-oncology in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020; 9:e017787. PMID: 32713239.64. Evans WK, Ashbury FD, Hogue GL, Smith A, Pun J. Implementing a regional oncology information system: approach and lessons learned. Curr Oncol. 2014; 21:224–233. PMID: 25302031.65. Sadler D, Chaulagain C, Alvarado B, et al. Practical and cost-effective model to build and sustain a cardio-oncology program. Cardiooncology. 2020; 6:9. PMID: 32690995.66. Herrmann J, Lenihan D, Armenian S, et al. Defining cardiovascular toxicities of cancer therapies: an International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS) consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022; 43:280–299. PMID: 34904661.67. Jahangir E. The need for precision cardio-oncology [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: American College of Cardiology;2020. cited 2022 August 2. Available from: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/09/21/19/13/the-need-for-precision-cardio-oncology.68. Rhee JW, Ky B, Armenian SH, Yancy CW, Wu JC. Primer on biomarker discovery in cardio-oncology: application of omics technologies. JACC CardioOncol. 2020; 2:379–384. PMID: 33073248.69. Gerik L. Cardio-oncology, then and now: an interview with Barry Trachtenberg. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc J. 2019; 15:e1–e3.70. Dreyfuss AD, Bravo PE, Koumenis C, Ky B. Precision cardio-oncology. J Nucl Med. 2019; 60:443–450. PMID: 30655328.71. Attia ZI, Kapa S, Lopez-Jimenez F, et al. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram. Nat Med. 2019; 25:70–74. PMID: 30617318.72. Zhou Y, Hou Y, Hussain M, et al. Machine learning-based risk assessment for cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction in 4300 longitudinal oncology patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020; 9:e019628. PMID: 33241727.73. Chaix MA, Parmar N, Kinnear C, et al. Machine learning identifies clinical and genetic factors associated with anthracycline cardiotoxicity in pediatric cancer survivors. JACC CardioOncol. 2020; 2:690–706. PMID: 34396283.74. Sadler DB, Moudgil R, Arco T, et al. Abstract 11675: Global cardio oncology registry: structure for a multinational collaboration. Circulation. 2021; 144(Suppl 1):11675.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

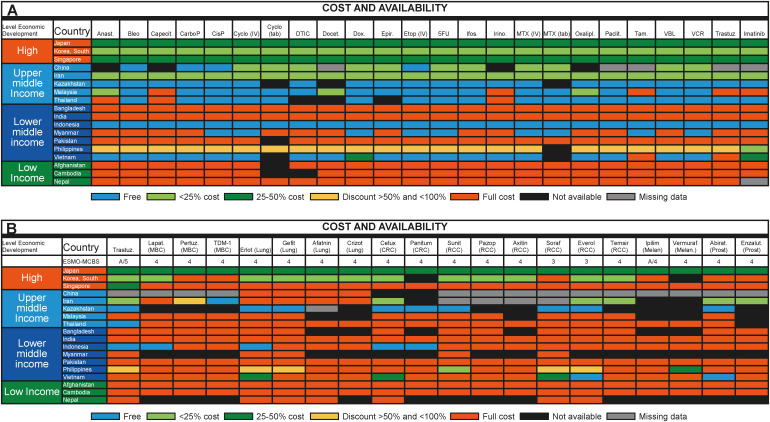

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The 4th European Society for Medical Oncology Asia Congress: bridging ultimate cancer care with real-world practice for the Asian practitioner in gynecological cancers

- Asian Society of Gynecologic Oncology (ASGO): a central platform against gynecologic cancers in Asia

- The Effect of Aging on Intervals, Axis, Heart Position, and Transitional Zone of Electrocardiogram

- Combat against cervical cancer-challenges in Asia Oceania: 5th Biennial Conference of the Asia Oceania Research Organization on Genital Infections & Neoplasia (AOGIN)

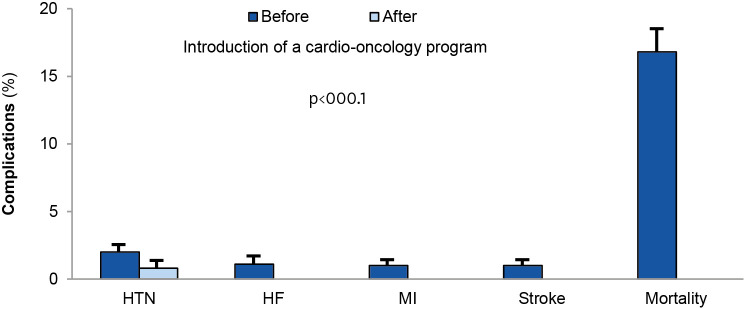

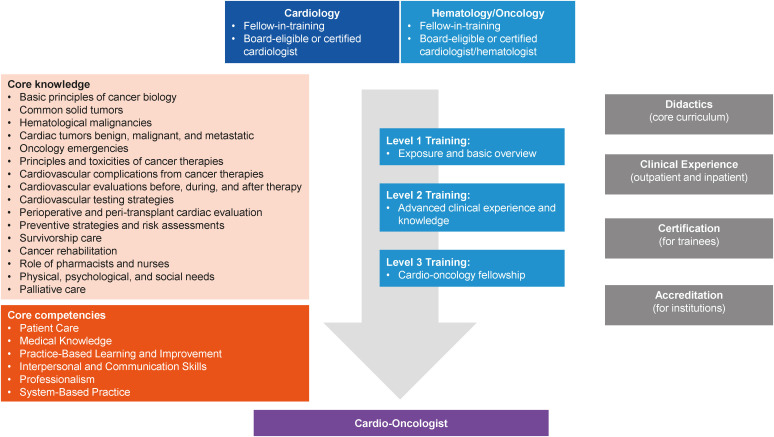

- Towards eradication of cervical cancer: 4th biennial conference of the Asia Oceania research organization on Genital Infections & Neoplasia (AOGIN)