Cancer Res Treat.

2023 Jan;55(1):15-27. 10.4143/crt.2021.1031.

Adherence to Cancer Prevention Guidelines and Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Population-Based Cohort Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea

- 2Department of Cancer Control and Population Health, National Cancer Center Graduate School of Cancer Science and Policy, Goyang, Korea

- KMID: 2537988

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.1031

Abstract

- Purpose

This study aimed to estimate the risk of cancer incidence and mortality according to adherence to lifestyle-related cancer prevention guidelines.

Materials and Methods

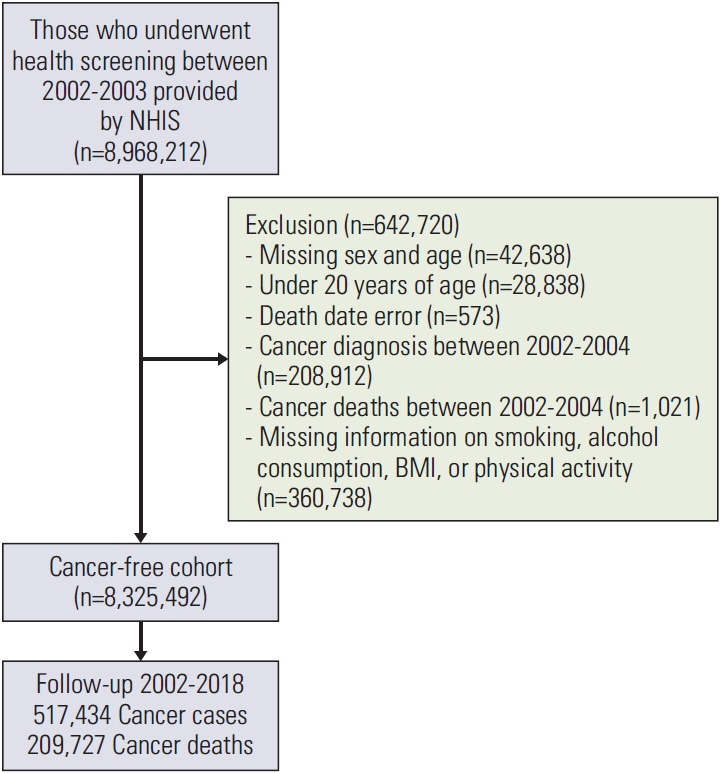

Men and women who participated in the general health screening program in 2002 and 2003 provided by the National Health Insurance Service were included (n=8,325,492). Self-reported smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity habits and directly measured body mass index were collected. The participants were followed up until the date of cancer onset or death or 31 December 2018. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) for cancer incidence and mortality according to different combinations of lifestyle behaviors.

Results

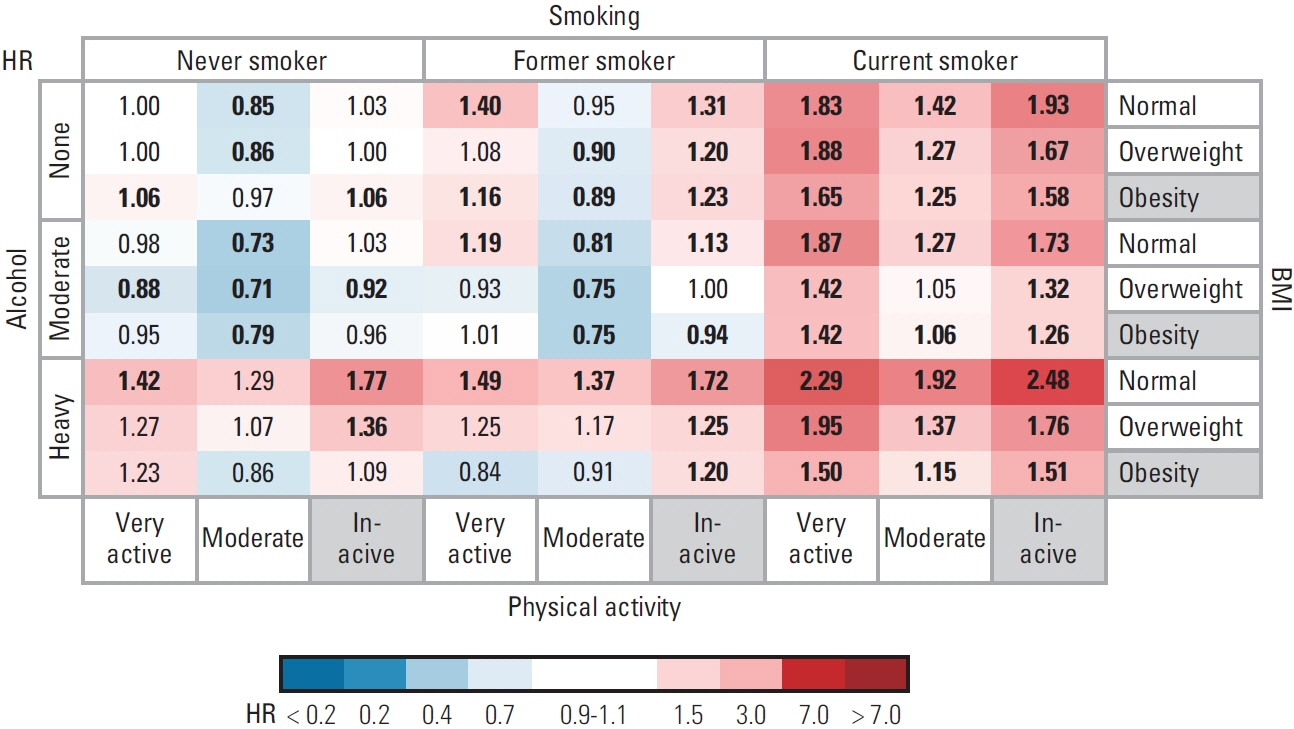

Only 6% of men and 15% of women engaged in healthy behavior at baseline, such as not smoking, not drinking alcohol, being moderately or highly physically active, and within a normal body mass index range. Compared to the best combination of healthy lifestyle behaviors, the weak and moderate associations with increased all cancer incidence (HR < 1.7) and mortality (HR < 2.5) were observed in those with heavy alcohol consumption and in former or current smokers. HRs of cancer mortality were significantly increased among current smokers in most combinations.

Conclusion

Compared to full adherence to cancer prevention recommendations, unhealthy behaviors increase cancer risk. As few people meet these recommendations, there is a great opportunity for cancer prevention.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M; Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group (Cancers). Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet. 2005; 366:1784–93.2. Schuz J, Espina C, Villain P, Herrero R, Leon ME, Minozzi S, et al. European Code against Cancer 4th edition: 12 ways to reduce your cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015; 39(Suppl 1):S1–10.3. World Cancer Research Fund International. Continuous update project expert report 2018 Recommendations and public health and policy implications [Internet]. London: WCRF International;2018. [cited 2021 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/diet-and-cancer/ .4. Rock CL, Thomson C, Gansler T, Gapstur SM, McCullough ML, Patel AV, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020; 70:245–71.5. Kaluza J, Harris HR, Hakansson N, Wolk A. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR 2018 recommendations for cancer prevention and risk of cancer: prospective cohort studies of men and women. Br J Cancer. 2020; 122:1562–70.6. Kabat GC, Matthews CE, Kamensky V, Hollenbeck AR, Rohan TE. Adherence to cancer prevention guidelines and cancer incidence, cancer mortality, and total mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015; 101:558–69.7. Kohler LN, Garcia DO, Harris RB, Oren E, Roe DJ, Jacobs ET. Adherence to diet and physical activity cancer prevention guidelines and cancer outcomes: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016; 25:1018–28.8. Hong S, Won YJ, Lee JJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Im JS, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2018. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:301–15.9. Lifestyle habits have a major impact on cancer. Dong-A Ilbo. 1991; Oct. 11–30.10. Ministry of Health and Welfare. First step to cancer prevention, follow the code against cancer [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2006. [cited 2022 Jan 11]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=39139 .11. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Avoid alcohol consumption! Get vaccine for cancer prevention! [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016. [cited 2022 Jan 11]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=330589 .12. Lee DH, Nam JY, Kwon S, Keum N, Lee JT, Shin MJ, et al. Lifestyle risk score and mortality in Korean adults: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020; 10:10260.13. Yun JE, Won S, Kimm H, Jee SH. Effects of a combined lifestyle score on 10-year mortality in Korean men and women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:673.14. Seong SC, Kim YY, Park SK, Khang YH, Kim HC, Park JH, et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e016640.15. Bang JS, Chung YH, Chung SJ, Lee HS, Song EH, Shin YK, et al. Clinical effect of a polysaccharide-rich extract of Acanthopanax senticosus on alcohol hangover. Pharmazie. 2015; 70:269–73.16. Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015; 112:580–93.17. Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2002; 2:8.18. Colditz GA, Atwood KA, Emmons K, Monson RR, Willett WC, Trichopoulos D, et al. Harvard report on cancer prevention volume 4: Harvard Cancer Risk Index. Risk Index Working Group, Harvard Center for Cancer Prevention. Cancer Causes Control. 2000; 11:477–88.19. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Awareness of ‘cancer is preventable’ greatly improved in 10 years [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2017. [cited 2022 Jan 11]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=338837 .20. Shams-White MM, Brockton NT, Mitrou P, Romaguera D, Brown S, Bender A, et al. Operationalizing the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) cancer prevention recommendations: a standardized scoring system. Nutrients. 2019; 11:1572.21. Park S, Jee SH, Shin HR, Park EH, Shin A, Jung KW, et al. Attributable fraction of tobacco smoking on cancer using population-based nationwide cancer incidence and mortality data in Korea. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:406.22. Kim S, Choi S, Kim J, Park S, Kim YT, Park O, et al. Trends in health behaviors over 20 years: findings from the 1998–2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiol Health. 2021; 43:e2021026.23. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2019 OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing;2019.24. Park S, Shin HR, Lee B, Shin A, Jung KW, Lee DH, et al. Attributable fraction of alcohol consumption on cancer using population-based nationwide cancer incidence and mortalitydata in the Republic of Korea. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:420.25. GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018; 392:1015–35.26. Naimi TS, Stockwell T, Zhao J, Xuan Z, Dangardt F, Saitz R, et al. Selection biases in observational studies affect associations between ‘moderate’ alcohol consumption and mortality. Addiction. 2017; 112:207–14.27. Stockwell T, Zhao J, Panwar S, Roemer A, Naimi T, Chikritzhs T. Do “moderate” drinkers have reduced mortality risk? A systematic review and meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016; 77:185–98.28. Ko H, Chang Y, Kim HN, Kang JH, Shin H, Sung E, et al. Low-level alcohol consumption and cancer mortality. Sci Rep. 2021; 11:4585.29. Viner B, Barberio AM, Haig TR, Friedenreich CM, Brenner DR. The individual and combined effects of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking on site-specific cancer risk in a prospective cohort of 26,607 adults: results from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project. Cancer Causes Control. 2019; 30:1313–26.30. French MT, Popovici I, Maclean JC. Do alcohol consumers exercise more? Findings from a national survey. Am J Health Promot. 2009; 24:2–10.31. Chang JY, Choi S, Park SM. Association of change in alcohol consumption with cardiovascular disease and mortality among initial nondrinkers. Sci Rep. 2020; 10:13419.32. Leasure JL, Neighbors C, Henderson CE, Young CM. Exercise and alcohol consumption: what we know, what we need to know, and why it is important. Front Psychiatry. 2015; 6:156.33. Park S, Kim Y, Shin HR, Lee B, Shin A, Jung KW, et al. Population-attributable causes of cancer in Korea: obesity and physical inactivity. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e90871.34. Kim Y, Nho SJ, Woo G, Kim H, Park S, Kim Y, et al. Trends in the prevalence and management of major metabolic risk factors for chronic disease over 20 years: findings from the 1998–2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiol Health. 2021; 43:e2021028.35. Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011; 8:115.36. Stockwell T, Zhao J, Macdonald S. Who under-reports their alcohol consumption in telephone surveys and by how much?: an application of the ‘yesterday method’ in a national Canadian substance use survey. Addiction. 2014; 109:1657–66.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Adherence to Cancer Prevention Guidelines and Endometrial Cancer Risk: Evidence from a Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies

- Introduction of Relative Survival Analysis Program: Using Sample of Cancer Registry Data with Stata Software

- Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in Vietnam and Korea (1999-2017)

- Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research and Korean Cancer Prevention Guidelines and cancer risk: a prospective cohort study from the Health Examinees-Gem study

- Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Flight Crews