J Stroke.

2022 Jan;24(1):79-87. 10.5853/jos.2021.02530.

Effect of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on the Quality of Stroke Care in Stroke Units and Alternative Wards: A National Comparative Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

- 2The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

- 3Department of Neuroscience, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Clayton, Australia

- 4Stroke Services, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Australia

- 5The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia

- 6Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, Sydney, Australia

- 7Department of Clinical Medicine, St Vincent’s Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Darlinghurst, Australia

- 8Department of Neurology, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia

- 9Department of Neurology, Royal Hobart Hospital, Hobart, Australia

- 10Department of Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

- 11Nursing Research Institute, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia

- 12Department of Medicine and Neurology, Melbourne Brain Centre at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

- 13Stroke Foundation, Melbourne, Australia

- 14Department of Neurology, Canberra Hospital, Canberra, Australia

- 15Department of Neurology, Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service, Southport, Australia

- 16Department of Neurology, Mater Brisbane, South Brisbane, Australia

- 17Stroke Statewide Clinical Network, Healthcare Improvement Unit, Clinical Excellence, Queensland Health, Brisbane, Australia

- 18Department of Neurology, Monash Health, Clayton, Australia

- KMID: 2525333

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2021.02530

Abstract

- Background and Purpose

Changes to hospital systems were implemented from March 2020 in Australia in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, including decreased resources allocated to stroke units. We investigate changes in the quality of acute care for patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack during the pandemic according to patients’ treatment setting (stroke unit or alternate ward).

Methods

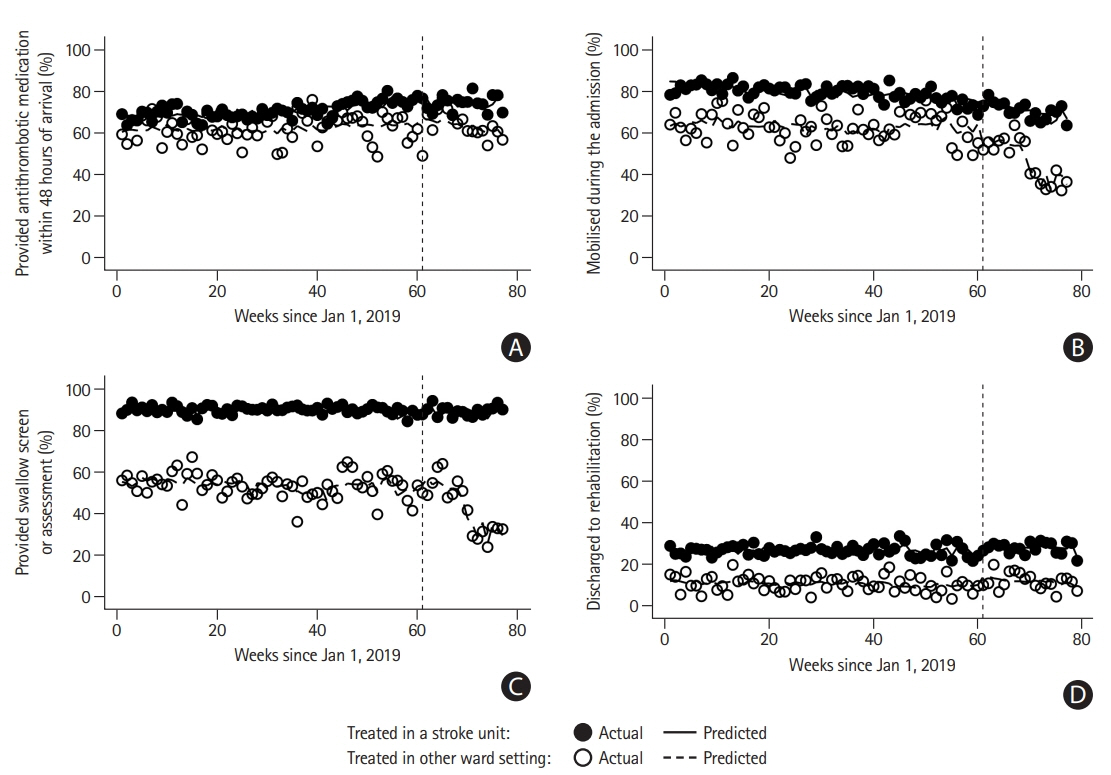

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients admitted with stroke or transient ischemic attack between January 2019 and June 2020 in the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry (AuSCR). The AuSCR monitors patients’ treatment setting, provision of allied health and nursing interventions, prescription of secondary prevention medications, and discharge destination. Weekly trends in the quality of care before and during the pandemic period were assessed using interrupted time series analyses.

Results

In total, 18,662 patients in 2019 and 8,850 patients in 2020 were included. Overall, 75% were treated in stroke units. Before the pandemic, treatment in a stroke unit was superior to alternate wards for the provision of all evidence-based therapies assessed. During the pandemic period, the proportion of patients receiving a swallow screen or assessment, being discharged to rehabilitation, and being prescribed secondary prevention medications decreased by 0.58% to 1.08% per week in patients treated in other ward settings relative to patients treated in stroke units. This change represented a 9% to 17% increase in the care gap between these treatment settings during the period of the pandemic that was evaluated (16 weeks).

Conclusions

During the first 6 months of the pandemic, widening care disparities between stroke units and alternate wards have occurred.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. McCabe R, Schmit N, Christen P, D’Aeth JC, Løchen A, Rizmie D. Adapting hospital capacity to meet changing demands during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. 2020; 18:329.

Article2. Brainin M. Stroke care and the COVID19 pandemic: words from our president. World Stroke Organization;https://www.world-stroke.org/news-and-blog/news/stroke-care-and-the-covid19-pandemic. 2020. Accessed September 22, 2021.3. Coote S, Cadilhac DA, O'Brien E, Middleton S; Acute Stroke Nurses Education Network (ASNEN) Steering Committee. Letter to the editor regarding: critical considerations for stroke management during COVID-19 pandemic in response to Inglis et al., Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(9):1263-1267. Heart Lung Circ. 2020; 29:1895–1896.4. Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 2013:CD000197.5. Cadilhac DA, Andrew NE, Lannin NA, Middleton S, Levi CR, Dewey HM, et al. Quality of acute care and long-term quality of life and survival: the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Stroke. 2017; 48:1026–1032.

Article6. Cadilhac DA, Kim J, Tod EK, Morrison JL, Breen SJ, Jaques K, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on care for stroke in Australia: emerging evidence from the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Front Neurol. 2021; 12:621495.

Article7. Cadilhac DA, Lannin NA, Anderson CS, Levi CR, Faux S, Price C, et al. Protocol and pilot data for establishing the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Int J Stroke. 2010; 5:217–226.

Article8. Tu JV, Willison DJ, Silver FL, Fang J, Richards JA, Laupacis A, et al. Impracticability of informed consent in the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:1414–1421.

Article9. Linden A, Arbor A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015; 15:480–500.

Article10. Markus HS, Brainin M. COVID-19 and stroke: a global World Stroke Organization perspective. Int J Stroke. 2020; 15:361–364.11. Chen CH, Liu CH, Chi NF, Sung PS, Hsieh CY, Lee M, et al. Maintenance of stroke care quality amid the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Taiwan. J Stroke. 2020; 22:407–411.

Article12. Desai SM, Guyette FX, Martin-Gill C, Jadhav AP. Collateral damage: impact of a pandemic on stroke emergency services. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020; 29:104988.13. Hoyer C, Ebert A, Huttner HB, Puetz V, Kallmünzer B, Barlinn K, et al. Acute stroke in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicenter study. Stroke. 2020; 51:2224–2227.14. Rudilosso S, Laredo C, Vera V, Vargas M, Renú A, Llull L, et al. Acute stroke care is at risk in the era of COVID-19: experience at a comprehensive stroke center in Barcelona. Stroke. 2020; 51:1991–1995.

Article15. Cadilhac DA, Ibrahim J, Pearce DC, Ogden KJ, McNeill J, Davis SM, et al. Multicenter comparison of processes of care between stroke units and conventional care wards in Australia. Stroke. 2004; 35:1035–1040.

Article16. Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit Acute Services Report 2019. Melbourne: Stroke Foundation;2019.17. Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:348–355.18. Schaffer AL, Dobbins TA, Pearson SA. Interrupted time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models: a guide for evaluating large-scale health interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021; 21:58.

Article19. Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, Gupta A, Kamel H, Lin E, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77:1–7.

Article20. Stroke Foundation. Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Stroke Foundation;2017. https://informme.org.au/en/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management. Assessed October 12, 2021.21. Krishnamurthi RV, Ikeda T, Feigin VL. Global, regional and country-specific burden of ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Neuroepidemiology. 2020; 54:171–179.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Stroke

- Organization of Stroke Care System: Stroke Unit and Stroke Center

- Stroke in the Time of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Experience of Two University Stroke Centers in Egypt

- Therapeutic Trends of Cerebrovascular Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Future Perspectives

- Primary and Comprehensive Stroke Centers: History, Value and Certification Criteria