J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Jun;36(22):e146. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e146.

Short and Long-term Outcomes of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Treatment according to Hospital Volume in Korea: a Nationwide Multicenter Registry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea

- 2Biostatics Department of Clinical Trial Center, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea

- 3Soonchunhyang Institute of Medi-Bio Science (SIMS), Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan, Korea

- 4Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju, Korea

- KMID: 2516578

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e146

Abstract

- Background

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is a potentially devastating cerebrovascular attack with a high proportion of poor outcomes and mortality. Recent studies have reported decreased mortality with the improvement in devices and techniques for treating ruptured aneurysms and neurocritical care. This study investigated the relationship between hospital volume and shortand long-term mortality in patients treated with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Methods

We selected subarachnoid hemorrhage patients treated with clipping and coiling from March–May 2013 to June–August 2014 using data from Acute Stroke Registry, and the selected subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) patients were tracked in connection with data of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service to evaluate the short-term and long-term mortality.

Results

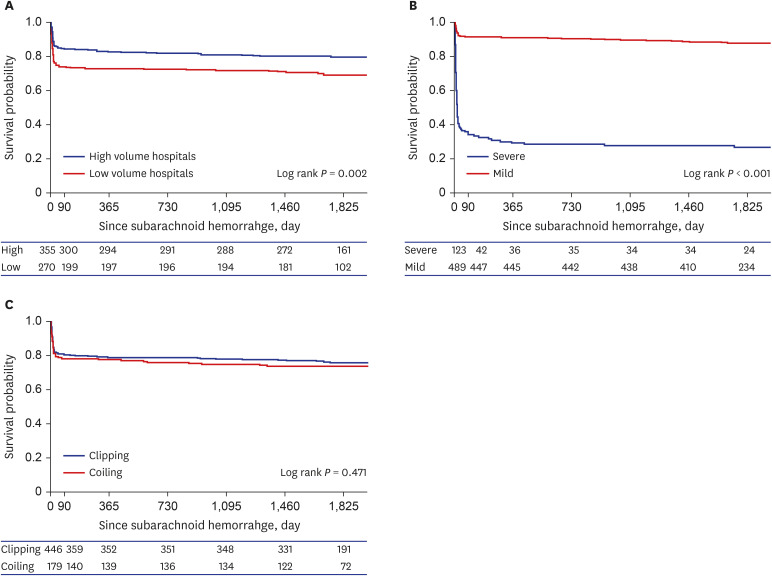

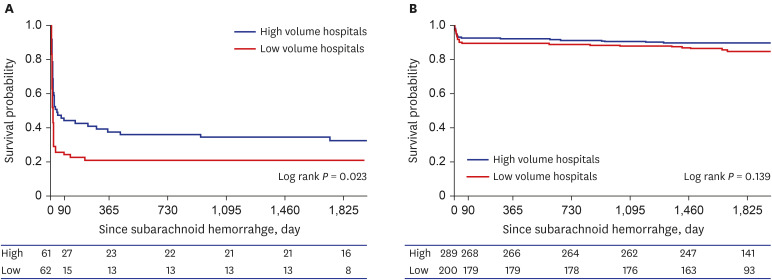

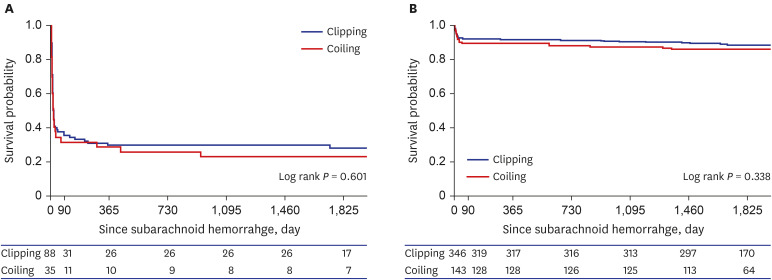

A total of 625 subarachnoid hemorrhage patients were admitted to high-volume hospitals (n = 355, 57%) and low-volume hospitals (n = 270, 43%) for six months. The mortality of SAH patients treated with clipping and coiling was 12.3%, 20.2%, 21.4%, and 24.3% at 14 days, three months, one year, and five years, respectively. The short-term and long-term mortality in high-volume hospitals was significantly lower than that in low-volume hospitals. On Cox regression analysis of death in patients with severe clinical status, lowvolume hospitals had significantly higher mortality than high-volume hospitals during shortterm follow-up. On Cox regression analysis in the mild clinical status group, there was no statistical difference between high-volume hospitals and low-volume hospitals.

Conclusion

In subarachnoid hemorrhage patients treated with clipping and coiling, lowvolume hospitals had higher short-term mortality than high-volume hospitals. These results from a nationwide database imply that acute SAH should be treated by a skilled neurosurgeon with adequate facilities in a high-volume hospital.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

High-Volume Hospital Had Lower Mortality of Severe Intracerebral Hemorrhage Patients

Sang-Won Park, James Jisu Han, Nam Hun Heo, Eun Chae Lee, Dong-Hun Lee, Ji Young Lee, Boung Chul Lee, Young Wha Lim, Gui Ok Kim, Jae Sang Oh

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2024;67(6):622-636. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2023.0205.Epidemiology and Functional Outcome of Acute Stroke Patients in Korea Using Nationwide data

Seungmin Shin, Young Woo Kim, Seung Hun Sheen, Sukh Que Park, Sung-Chul Jin, Jin Pyeong Jeon, Ji Young Lee, Boung Chul Lee, Young Wha Lim, Gui Ok Kim, Youg Uk Kwon, Yu Ra Lee, So Young Han, Jae Sang Oh

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2025;68(2):159-176. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2024.0118.

Reference

-

1. Chan V, O'Kelly C, McQuiggan J, Zagorski B, Hill MD, O'Kelly C. Declining admission and mortality rates for subarachnoid hemorrhage in Canada between 2004 and 2015. Stroke. 2019; 50(5):e133. PMID: 30909838.

Article2. Suarez JI, Zaidat OO, Suri MF, Feen ES, Lynch G, Hickman J, et al. Length of stay and mortality in neurocritically ill patients: impact of a specialized neurocritical care team. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(11):2311–2317. PMID: 15640647.

Article3. Rincon F, Rossenwasser RH, Dumont A. The epidemiology of admissions of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in the United States. Neurosurgery. 2013; 73(2):217–222. PMID: 23615089.

Article4. Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Zabramski JM, Albuquerque FC, Hills NK, Russin JJ, et al. The barrow ruptured aneurysm trial: 6-year results. J Neurosurg. 2015; 123(3):609–617. PMID: 26115467.

Article5. Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Zabramski JM, Albuquerque FC, Hills NK, Nakaji P, et al. Ten-year analysis of saccular aneurysms in the barrow ruptured aneurysm trial. J Neurosurg. 2019; 132(3):771–776. PMID: 30849758.

Article6. Rush B, Romano K, Ashkanani M, McDermid RC, Celi LA. Impact of hospital case-volume on subarachnoid hemorrhage outcomes: a nationwide analysis adjusting for hemorrhage severity. J Crit Care. 2017; 37:240–243. PMID: 27663296.

Article7. Starke RM, Komotar RJ, Kim GH, Kellner CP, Otten ML, Hahn DK, et al. Evaluation of a revised Glasgow Coma Score scale in predicting long-term outcome of poor grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. J Clin Neurosci. 2009; 16(7):894–899. PMID: 19375327.

Article8. Neifert SN, Martini ML, Hardigan T, Ladner TR, MacDonald RL, Oermann EK. Trends in incidence and mortality by hospital teaching status and location in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2020; 142:e253–9. PMID: 32599190.

Article9. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346(15):1128–1137. PMID: 11948273.

Article10. Davies JM, Ozpinar A, Lawton MT. Volume-outcome relationships in neurosurgery. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2015; 26(2):207–218. PMID: 25771276.

Article11. Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, Sandercock P, Clarke M, Shrimpton J, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002; 11(6):304–314. PMID: 17903891.12. Ikawa F, Michihata N, Matsushige T, Abiko M, Ishii D, Oshita J, et al. In-hospital mortality and poor outcome after surgical clipping and endovascular coiling for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage using nationwide databases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2020; 43(2):655–667. PMID: 30941595.

Article13. Bekelis K, Gottlieb D, Su Y, O'Malley AJ, Labropoulos N, Goodney P, et al. Surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling for elderly patients presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016; 8(9):913–918. PMID: 26311713.

Article14. McDougall CG, Spetzler RF, Zabramski JM, Partovi S, Hills NK, Nakaji P, et al. The barrow ruptured aneurysm trial. J Neurosurg. 2012; 116(1):135–144. PMID: 22054213.

Article15. Sade B, Mohr G. Critical appraisal of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Neurol India. 2004; 52(1):32–35. PMID: 15069236.16. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40(5):373–383. PMID: 3558716.

Article17. Gotoh O, Tamura A, Yasui N, Suzuki A, Hadeishi H, Sano K. Glasgow Coma Scale in the prediction of outcome after early aneurysm surgery. Neurosurgery. 1996; 39(1):19–24. PMID: 8805136.

Article18. Kassell NF, Torner JC, Haley EC Jr, Jane JA, Adams HP, Kongable GL. The international cooperative study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. Part 1: overall management results. J Neurosurg. 1990; 73(1):18–36. PMID: 2191090.19. Kassell NF, Torner JC, Jane JA, Haley EC Jr, Adams HP. The international cooperative study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. Part 2: surgical results. J Neurosurg. 1990; 73(1):37–47. PMID: 2191091.20. Barker FG 2nd, Amin-Hanjani S, Butler WE, Ogilvy CS, Carter BS. In-hospital mortality and morbidity after surgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the United States, 1996–2000: the effect of hospital and surgeon volume. Neurosurgery. 2003; 52(5):995–1007. PMID: 12699540.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Association between Levetiracetam Use and Survival in Patients with Glioblastoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study

- Prognosis and Prognostic Factors of Caudate Hemorrhage

- Long-term efficacy of vasodilating β-blocker in patients with acute myocardial infarction: nationwide multicenter prospective registry

- Epidemiology and Functional Outcome of Acute Stroke Patients in Korea Using Nationwide data

- Symptomatic Tarlov Cyst Following Spontaneous Subarachnoid Hemorrhage