J Korean Acad Oral Health.

2020 Dec;44(4):214-221. 10.11149/jkaoh.2020.44.4.214.

Studies on inhibition of gingival fibroblast proliferation by nicotine concentration

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Oral Health, College of Health Science, Dankook University, Cheonan,

- 2Department of Dental Hygiene, Andong Science College, Andong,

- 3Departments of Pediatric Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea

- 4Departments of Preventive Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea

- KMID: 2510253

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11149/jkaoh.2020.44.4.214

Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the effect of nicotine on the healing of an oral cavity wound, high and low concentrations of nicotine were administered on human gingival fibroblasts.

Methods

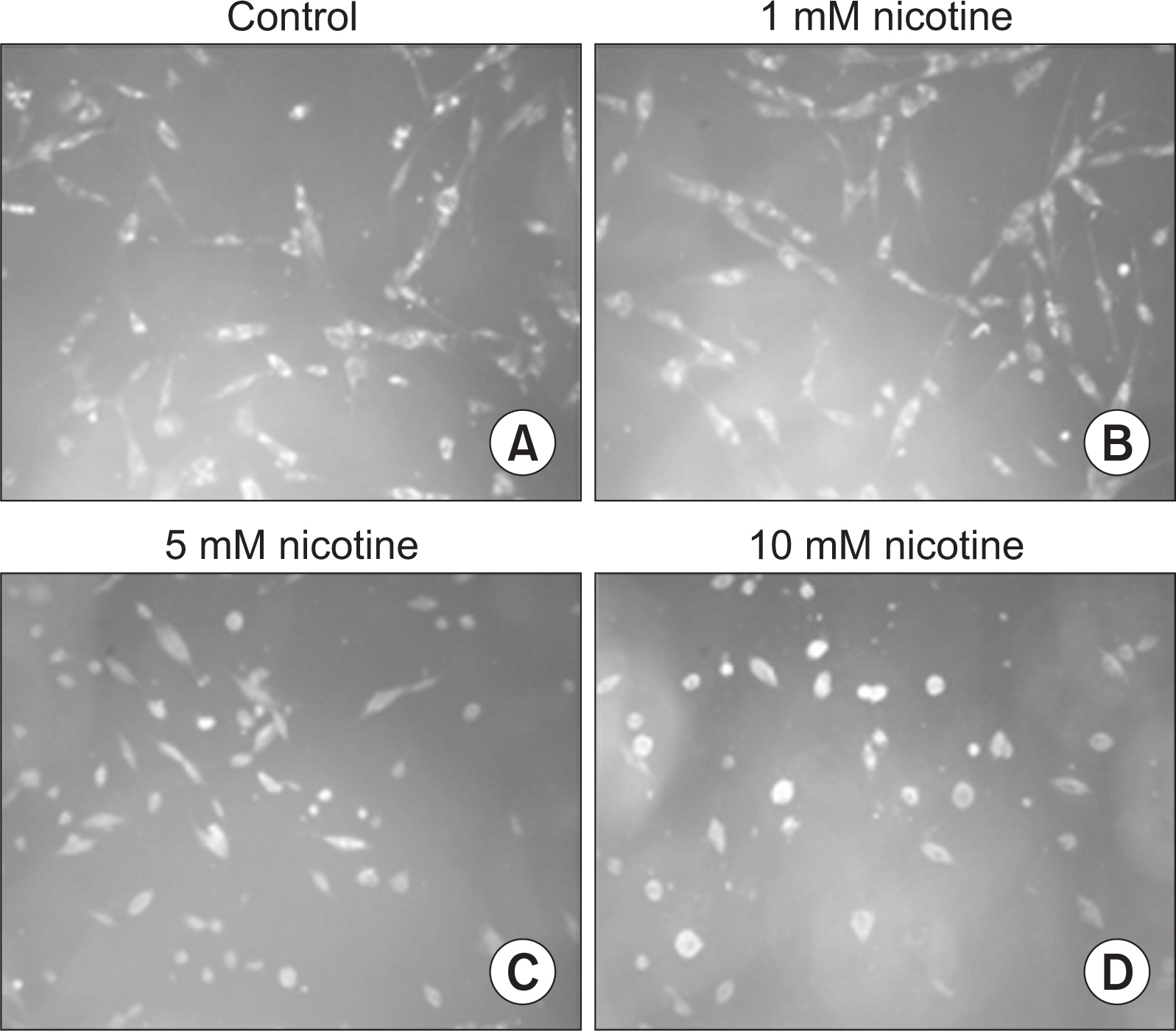

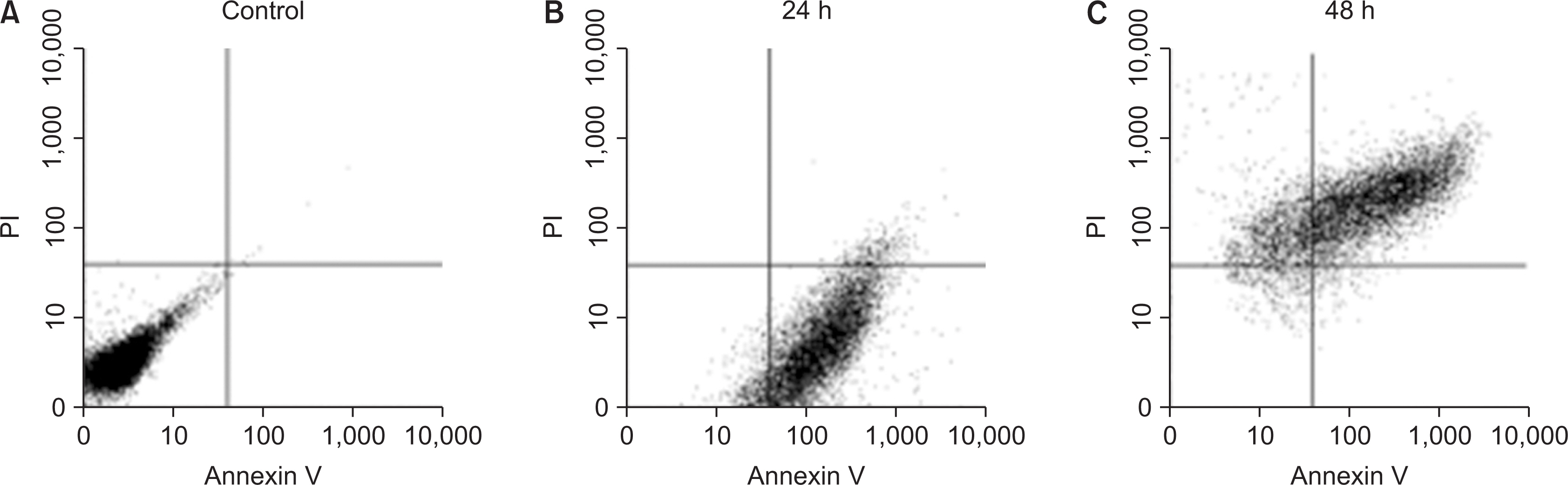

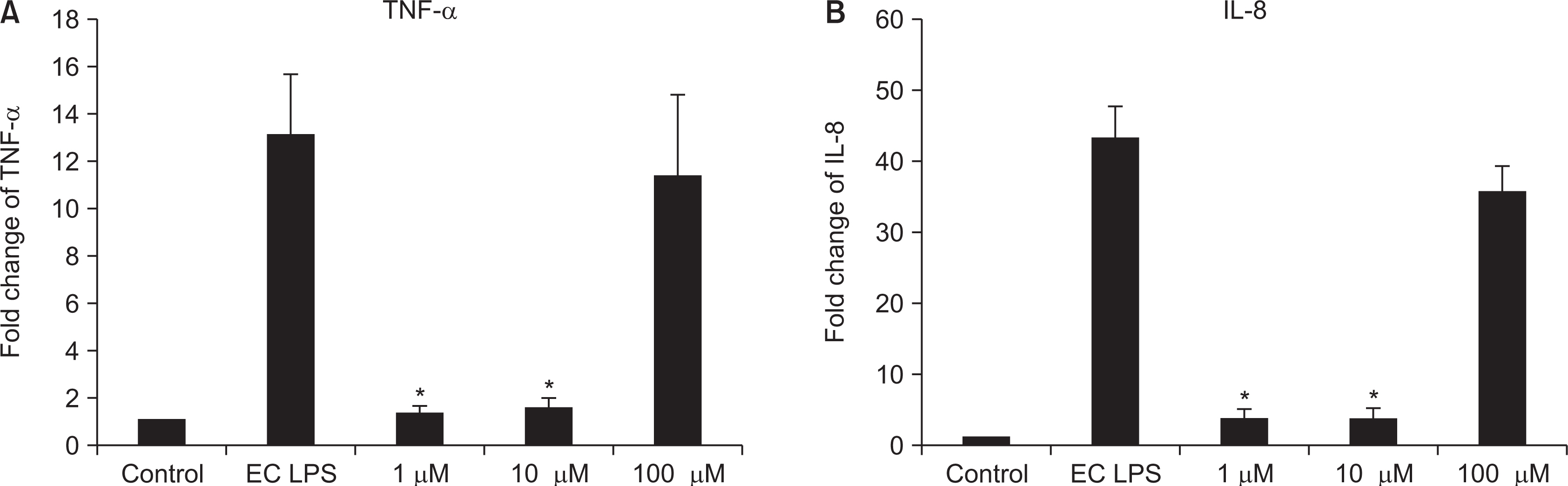

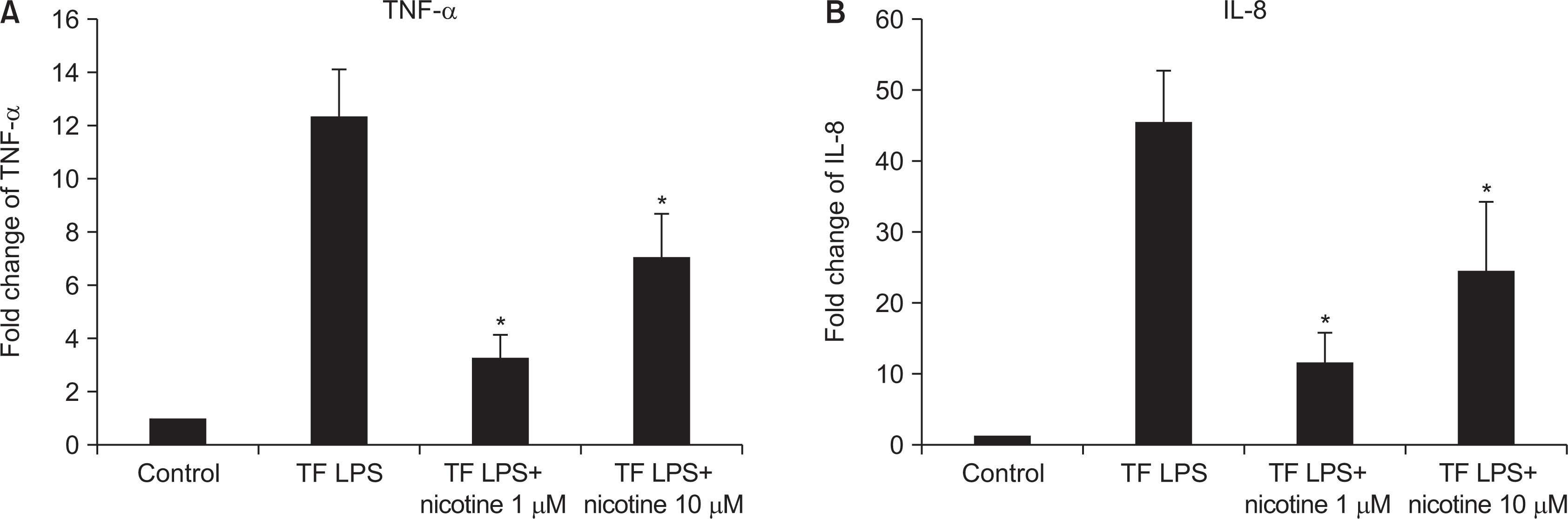

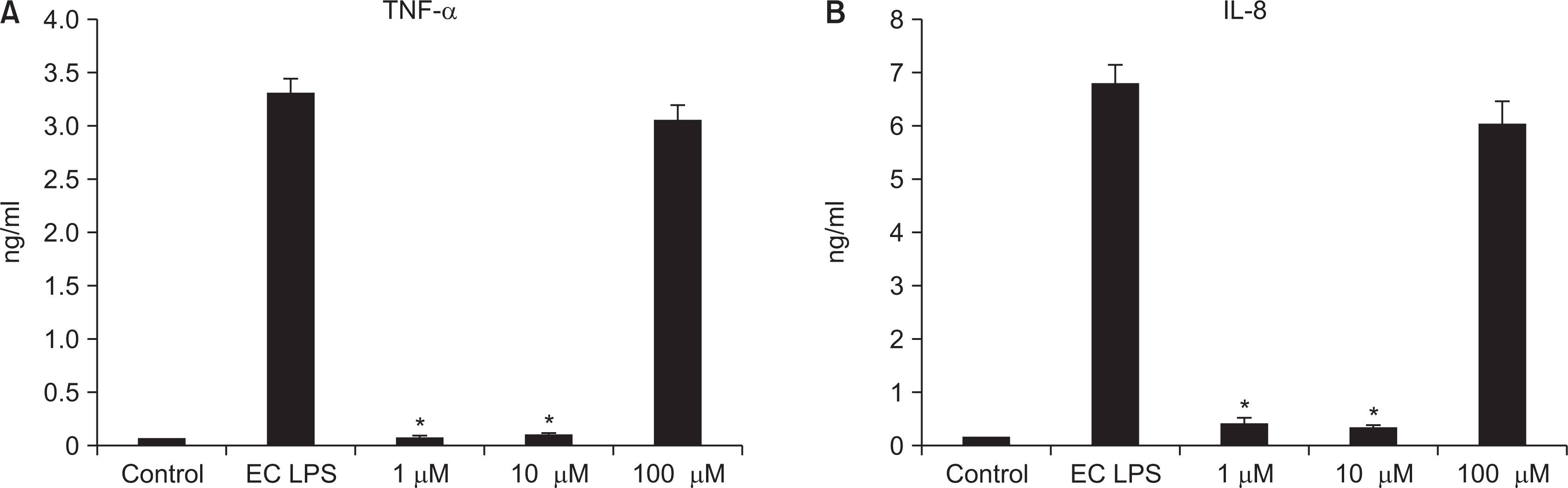

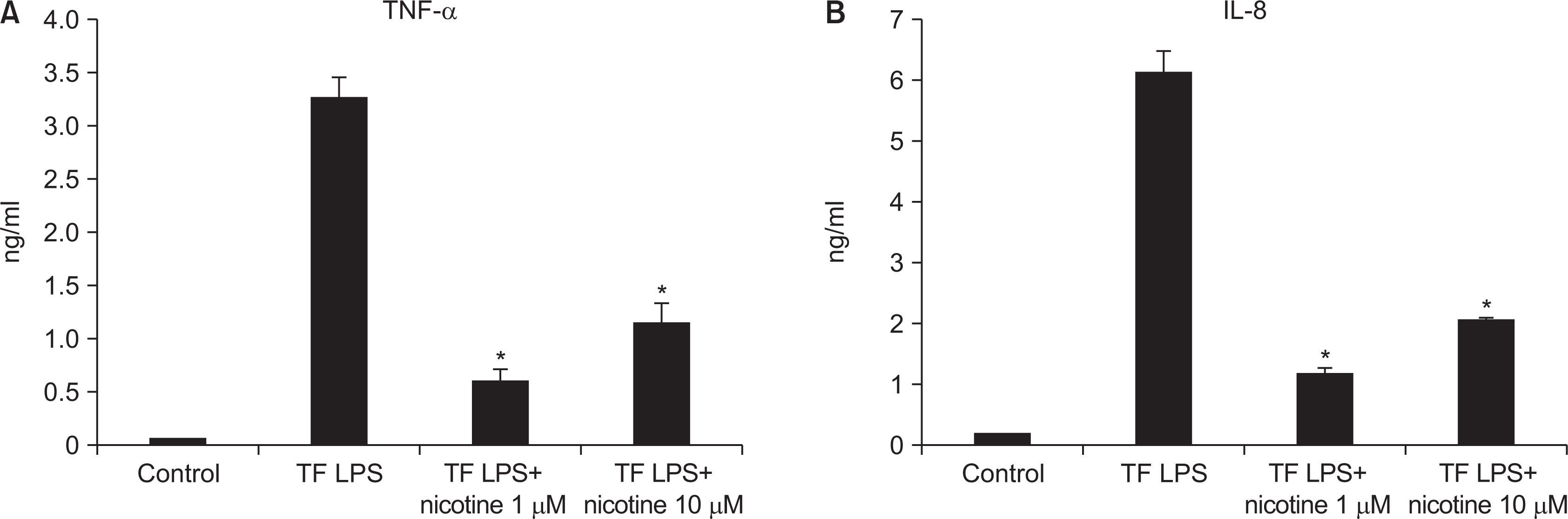

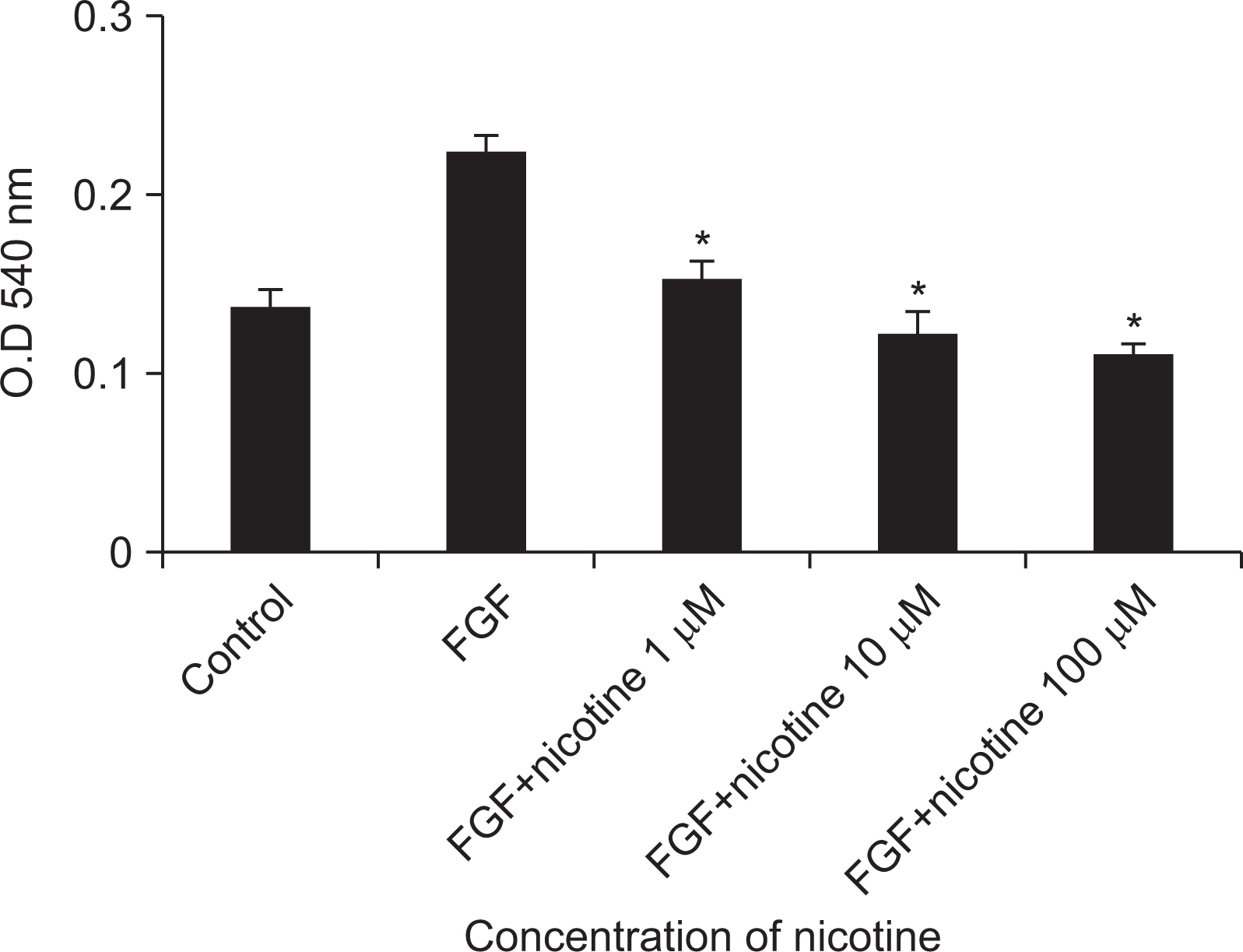

Nicotine at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mM were administered to gingival fibroblasts to evaluate the survival capability of the cells. Nicotine at 0.1 mM, a nonapoptotic concentration, was administered to evaluate apoptosis using Annexin V-FITC/Propidium Iodide cell staining. Nicotine at 1, 10, and 100 mM were administered to measure the expression of inflammatory cytokines, which was measured by RT-PCR and ELISA. FGF was treated with an additional 1, 10, or 100 mM of nicotine to evaluate cell proliferation and wound healing.

Results

As the concentration of nicotine increased (0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mM), the survival capability of the cells reduced. When cells were exposed to low nicotine concentration (0.1 mM) for 24 h, apoptosis occurred. Moreover, if the cell was exposed for 48 h, cell apoptosis occurred with necrosis. As the concentration of nicotine increased (1, 10, and 100 mM), more inflammatory cytokines were expressed. When EC LPS and TF LPS were combined with a low concentration of nicotine (1 and 10 mM), the expression of inflammatory cytokines was suppressed. The FGF level decreased as the nicotine concentration increased (1, 10, and 100 mM).

Conclusions

Nicotine interferes with the wound healing process of gingival fibroblasts. To maintain the wound healing process after a surgery or dental procedure, cessation of smoking is recommended.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Bonita R, Magnusson R, Bovet P, Zhao D, Malta DC, Geneau R, Suh I, Thankappan KR, McKee M, Hospedales J, de Courten M, Capewell S, Beaglehole R. 2013; Country actions to meet UN commitments on non-communicable diseases: a stepwise approach. Lancet. 381:575–584. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61993-X. PMID: 23410607.

Article2. Jee SH, Yun JE, Park JY, Sul JW, Kim IS. 2005; Smoking and cause of death in Korea: 11 years follow-up prospective study. Korean J Epidemiol. 27:182–190.3. Yun YH, Jung KW, Bae JM, Lee JS, Shin SA, Park SM, Yoo TW, Huh BY. 2005; Cigarette smoking and cancer incidence risk in adult men: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. Cancer Detect Prev. 29:15–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.08.006. PMID: 15734213.

Article4. Hayes RB, Bravo-Otero E, Kleinman DV, Brown LM, Fraumeni JF Jr, Harty LC, Winn DM. 1999; Tobacco and alcohol use and oral cancer in Puerto Rico. Cancer Causes Control. 10:27–33. DOI: 10.1023/A:1008876115797. PMID: 10334639.5. Paik DI, Kim HD, Shin SC, Cho JW, Park YD, Kim DK, et al. 2011. Clinical Preventive Dentistry. 5th ed. Komoonsa;Seoul: p. 431–442.6. Baab DA, Oberg PA. 1987; The effect of cigarette smoking on gingival blood flow in humans. J Clin Periodontol. 14:418–424. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1987.tb01547.x. PMID: 2957396.

Article7. Kye SB, Han SB. 2001; Effects of cigarette smoking on periodontal status. J Korean Acad Periodontol. 31:803–810. DOI: 10.5051/jkape.2001.31.4.803.

Article8. Johnson GK, Hill M. 2004; Cigarette smoking and the periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 75:196–209. DOI: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.196. PMID: 15068107.

Article9. Millar WJ, Locker D. 2007; Smoking and oral health status. J Can Dent Assoc. 73:155. PMID: 17355806.10. Sherr CJ. 1993; Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell. 73:1059–1065. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90636-5. PMID: 7880531.

Article11. Hwang CH, Park MY, Park KK, Choi SH, Cho KS, Kim CK, Chai JK. 1998; The Effects of Nicotine and NNK on gingival fibroblast. J Korean Acad Periodontol. 28:703–721. DOI: 10.5051/jkape.1998.28.4.703.

Article12. Copeland RL Jr, Das JR, Kanaan YM, Taylor RE, Tizabi Y. 2007; Antiapoptotic effects of nicotine in its protection against salsolinol-induced cytotoxicity. Neurotox Res. 12:61–69. DOI: 10.1007/BF03033901. PMID: 17513200.

Article13. Holt PG, Keast D. 1977; Environmentally induced changes in immunological function: acute and chronic effects of inhalation of tobacco smoke and other atmospheric contaminants in man and experimental animals. Bacteriol Rev. 41:205–216. DOI: 10.1128/BR.41.1.205-216.1977. PMID: 405003. PMCID: PMC413999.

Article14. Raulin LA, McPherson JC, McQuade MJ, Hanson BS. 1988; The effect of nicotine on the attachment of human fibroblasts to glass and human root surfaces in vitro. J Periodontol. 59:318–325. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.5.318. PMID: 3164382.15. Mariotti A, Cochran DL. 1990; Characterization of fibroblasts derived from human periodontal ligament and gingiva. J Periodontol. 61:103–111. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.2.103. PMID: 2313526.

Article16. Caffesse RG, Quiñones CR. 1993; Polypeptide growth factors and attachment proteins in periodontal wound healing and regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 1:69–79. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1993.tb00208.x. PMID: 8401862.

Article17. Lee TJ, Kwak HB, Kim HH, Lee ZH, Chung DK, Baek NI, Kim JY. 2007; Methanol extracts of Stewartia koreana inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene expression by blocking NF-kappaB transactivation in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. Mol Cells. 23:398–404. PMID: 17646715.18. Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. 2001; Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 357:593–615. DOI: 10.1042/bj3570593. PMID: 11463332. PMCID: PMC1221991.

Article19. Chamson A, Frey J, Hivert M. 1982; Effects of tobacco smoke extracts on collagen biosynthesis by fibroblast cell cultures. J Toxicol Environ Health. 9:921–932. DOI: 10.1080/15287398209530214. PMID: 7120518.

Article20. Tipton DA, Dabbous MK. 1995; Effects of nicotine on proliferation and extracellular matrix production of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. J Periodontol. 66:1056–1064. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.12.1056. PMID: 8683418.

Article21. Peacock ME, Sutherland DE, Schuster GS, Brennan WA, O'Neal RB, Strong SL, Van Dyke TE. 1993; The effect of nicotine on reproduction and attachment of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. J Periodontol. 64:658–665. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.658. PMID: 8366415.

Article22. Checchi L, Ciapetti G, Monaco G, Ori G. 1999; The effects of nicotine and age on replication and viability of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. J Clin Periodontol. 26:636–642. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.1999.261002.x. PMID: 10522774.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Effects of Nicotine and NNK on gingival fibroblast

- The Effect of Mitomycine C (MMC) on Inhibition of Pterygial Fibroblast Proliferation

- Effects of Nicotine on the Expression of Cell Cycle Regulatory Proteins of Human Gingival Fibroblasts

- Effects of Glycosaminoglycan on the Growth of Human Gingival Fibroblast

- Attachment and proliferation of human gingival fibroblasts on the implant abutment materials