2020 Korean Society of Myocardial Infarction Expert Consensus Document on Pharmacotherapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Department of Cardiology, Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine and Cardiovascular Center, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon, Korea

- 5Heart Vascular and Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiovascular Centre, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 7Division of Cardiovascular, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea

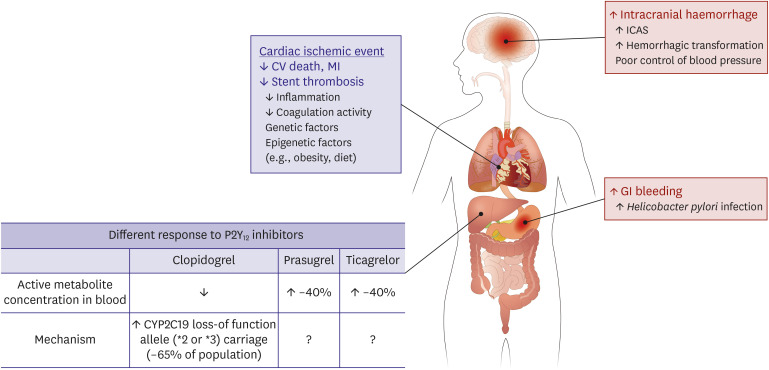

- 8Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea

- 9Cardiology Division, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 10Cardiovascular Center, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, Seoul, Korea

- 11Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 12School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2507003

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0196

Abstract

- Clinical practice guidelines published by the European Society of Cardiology and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association summarize the available evidence and provide recommendations for health professionals to enable appropriate clinical decisions and improve clinical outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, most current guidelines are based on studies in non-Asian populations in the pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) era. The Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry is the first nationwide registry to document many aspects of AMI from baseline characteristics to treatment strategies. There are well-organized ongoing and published randomized control trials especially for antiplatelet therapy among Korean patients with AMI. Here, members of the Task Force of the Korean Society of Myocardial Infarction review recent published studies during the current PCI era, and have summarized the expert consensus for the pharmacotherapy of AMI.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Balancing Between Ischemic and Bleeding Risk in PCI Patients With ‘Bi-Risk’

Mahn-Won Park

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(4):338-340. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0429.Identifying and Solving Gaps in Pre- and In-Hospital Acute Myocardial Infarction Care in Asia-Pacific Countries

Paul Jie Wen Tern, Amar Vaswani, Khung Keong Yeo

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(9):594-605. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0169.2024 Korean Society of Myocardial Infarction/National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency Guideline for the Pharmacotherapy of Acute Coronary Syndromes

Hyun Kuk Kim, Seungeun Ryoo, Seung Hun Lee, Doyeon Hwang, Ki Hong Choi, Jungeun Park, Hyeon-Jeong Lee, Chang-Hwan Yoon, Jang Hoon Lee, Joo-Yong Hahn, Young Joon Hong, Jin Yong Hwang, Myung Ho Jeong, Dong Ah Park, Chang-Wook Nam, Weon Kim

Korean Circ J. 2024;54(12):767-793. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2024.0257.

Reference

-

1. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:54–63. PMID: 22216842.

Article2. Lee SW, Kim HC, Lee HS, Suh I. Thirty-year trends in mortality from cardiovascular diseases in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2015; 45:202–209. PMID: 26023308.

Article3. Kim RB, Kim BG, Kim YM, et al. Trends in the incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction and stroke in Korea, 2006–2010. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:16–24. PMID: 23341707.

Article4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:267–315. PMID: 26320110.5. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:e139–228. PMID: 25260718.6. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:119–177. PMID: 28886621.7. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:e78–140. PMID: 23256914.8. Lee JH, Yang DH, Park HS, et al. Suboptimal use of evidence-based medical therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction from the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry: prescription rate, predictors, and prognostic value. Am Heart J. 2010; 159:1012–1019. PMID: 20569714.

Article9. Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015; 131:980–987. PMID: 25688146.10. Kang J, Park KW, Palmerini T, et al. Racial differences in ischaemia/bleeding risk trade-off during anti-platelet therapy: individual patient level landmark meta-analysis from seven RCTs. Thromb Haemost. 2019; 119:149–162. PMID: 30597509.

Article11. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003; 361:13–20. PMID: 12517460.

Article12. Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, et al. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:733–742. PMID: 12930925.

Article13. Thrane PG, Kristensen SD, Olesen KK, et al. 16-year follow-up of the Danish Acute Myocardial Infarction 2 (DANAMI-2) trial: primary percutaneous coronary intervention vs. fibrinolysis in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:847–854. PMID: 31504424.

Article14. GUSTO Investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:673–682. PMID: 8204123.15. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet. 1988; 2:349–360. PMID: 2899772.16. Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1179–1189. PMID: 15758000.

Article17. Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 366:1607–1621. PMID: 16271642.18. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 Investigators. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with enoxaparin, abciximab, or unfractionated heparin: the ASSENT-3 randomised trial in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2001; 358:605–613. PMID: 11530146.19. Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:1477–1488. PMID: 16537665.

Article20. Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, et al. Fibrinolysis or primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1379–1387. PMID: 23473396.21. Sinnaeve PR, Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, et al. ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients randomized to a pharmaco-invasive strategy or primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Strategic Reperfusion Early After Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) 1-year mortality follow-up. Circulation. 2014; 130:1139–1145. PMID: 25161043.22. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Safety and benefit of early elective percutaneous coronary intervention after successful thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 103:1333–1338. PMID: 19427424.

Article23. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Pharmacoinvasive strategy versus primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a propensity score-matched analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016; 9:e003508. PMID: 27582112.

Article24. Bonnefoy E, Steg PG, Boutitie F, et al. Comparison of primary Angioplasty and Pre-hospital fibrinolysis In acute Myocardial infarction (CAPTIM) trial: a 5-year follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:1598–1606. PMID: 19429632.

Article25. Chen ZM, Pan HC, Chen YP, et al. Early intravenous then oral metoprolol in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 366:1622–1632. PMID: 16271643.26. Sterling LH, Filion KB, Atallah R, Reynier P, Eisenberg MJ. Intravenous beta-blockers in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 228:295–302. PMID: 27866018.

Article27. Ibanez B, Macaya C, Sánchez-Brunete V, et al. Effect of early metoprolol on infarct size in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the Effect of Metoprolol in Cardioprotection During an Acute Myocardial Infarction (METOCARD-CNIC) trial. Circulation. 2013; 128:1495–1503. PMID: 24002794.28. Pizarro G, Fernández-Friera L, Fuster V, et al. Long-term benefit of early pre-reperfusion metoprolol administration in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the METOCARD-CNIC trial (Effect of Metoprolol in Cardioprotection During an Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:2356–2362. PMID: 24694530.29. Roolvink V, Ibáñez B, Ottervanger JP, et al. Early intravenous beta-blockers in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction before primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 67:2705–2715. PMID: 27050189.30. Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001; 357:1385–1390. PMID: 11356434.31. Korhonen MJ, Robinson JG, Annis IE, et al. Adherence tradeoff to multiple preventive therapies and all-cause mortality after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:1543–1554. PMID: 28935030.

Article32. Dondo TB, Hall M, West RM, et al. β-blockers and mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients without heart failure or ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2710–2720. PMID: 28571635.

Article33. Neumann A, Maura G, Weill A, Alla F, Danchin N. Clinical events after discontinuation of β-blockers in patients without heart failure optimally treated after acute myocardial infarction: a cohort study on the french healthcare databases. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018; 11:e004356. PMID: 29653999.

Article34. Choo EH, Chang K, Ahn Y, et al. Benefit of β-blocker treatment for patients with acute myocardial infarction and preserved systolic function after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2014; 100:492–499. PMID: 24395980.

Article35. Yang JH, Hahn JY, Song YB, et al. Association of beta-blocker therapy at discharge with clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7:592–601. PMID: 24947717.36. Park JJ, Kim SH, Kang SH, et al. Effect of β-blockers beyond 3 years after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7:e007567. PMID: 29502101.37. Yang JH, Hahn JY, Song YB, et al. Angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular systolic function: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014; 349:g6650. PMID: 25398372.

Article38. Song PS, Seol SH, Seo GW, et al. Comparative effectiveness of angiotensin II receptor blockers versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors following contemporary treatments in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Korean Working Group in Myocardial Infarction (KorMI) registry. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2015; 15:439–449. PMID: 26153396.

Article39. Lee JH, Bae MH, Yang DH, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers as a first choice in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean J Intern Med. 2016; 31:267–276. PMID: 26701233.

Article40. Choi SY, Choi BG, Rha SW, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus angiotensin II receptor blockers in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 249:48–54. PMID: 28867244.

Article41. Byun JK, Choi BG, Rha SW, Choi SY, Jeong MH. Other Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) investigators. Comparison of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with diabetes mellitus and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis. 2018; 277:130–135. PMID: 30212681.

Article42. Choi IS, Park IB, Lee K, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors provide better long-term survival benefits to patients with AMI than angiotensin II receptor blockers after survival hospital discharge. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2019; 24:120–129.

Article43. Jeong HC, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Comparative assessment of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: surmountable vs. insurmountable antagonist. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 170:291–297. PMID: 24239100.

Article44. Park K, Kim YD, Kim KS, et al. The impact of a dose of the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan on post-myocardial infarction ventricular remodelling. ESC Heart Fail. 2018; 5:354–363. PMID: 29341471.

Article45. Song PS, Kim DK, Seo GW, et al. Spironolactone lowers the rate of repeat revascularization in acute myocardial infarction patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2014; 168:346–353.e3. PMID: 25173547.

Article46. Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, et al. Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1524–1534. PMID: 31475799.47. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:87–165. PMID: 30165437.48. Motovska Z, Hlinomaz O, Miklik R, et al. Prasugrel versus ticagrelor in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: multicenter randomized PRAGUE-18 Study. Circulation. 2016; 134:1603–1612. PMID: 27576777.49. Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:9–19. PMID: 22077192.

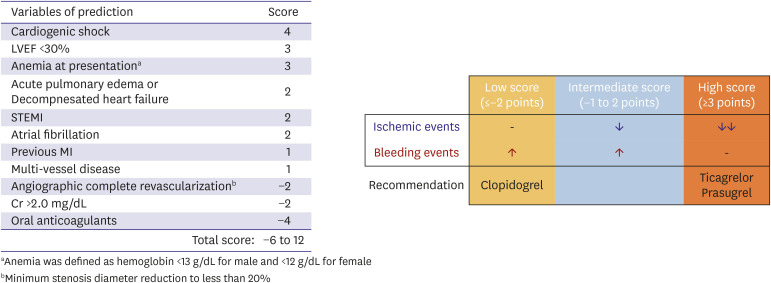

Article50. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:213–260. PMID: 28886622.51. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:407–477. PMID: 31504439.52. Bae JS, Ahn JH, Tantry US, Gurbel PA, Jeong YH. Should antithrombotic treatment strategies in east Asians differ from Caucasians? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2018; 16:459–476. PMID: 29345591.

Article53. Huo Y, Jeong YH, Gong Y, et al. 2018 update of expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Sci Bull (Beijing). 2019; 64:166–179.

Article54. Chen KY, Rha SW, Li YJ, et al. Triple versus dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2009; 119:3207–3214. PMID: 19528339.55. Park KH, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Comparison of short-term clinical outcomes between ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing successful revascularization; from Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry-National Institute of Health. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 215:193–200. PMID: 27128530.

Article56. Park KH, Jeong MH, Kim HK, et al. Comparison of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in Korean patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing successful revascularization. J Cardiol. 2018; 71:36–43. PMID: 28673508.

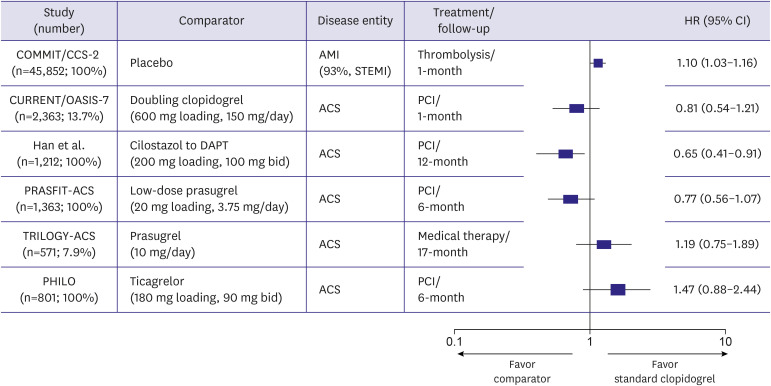

Article57. Kang J, Han JK, Ahn Y, et al. Third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors in East Asian acute myocardial infarction patients: a nationwide prospective multicentre study. Thromb Haemost. 2018; 118:591–600. PMID: 29534250.

Article58. Lee SH, Kim HK, Jeong MH, et al. Practical guidance for P2Y12 inhibitors in acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Article59. Yun JE, Kim YJ, Park JJ, et al. Safety and effectiveness of contemporary P2Y12 inhibitors in an East Asian population with acute coronary syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8:e012078. PMID: 31310570.

Article60. Park DW, Kwon O, Jang JS, et al. Clinically significant bleeding with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Korean patients with acute coronary syndromes intended for invasive management: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2019; 140:1865–1877. PMID: 31553203.61. Lee JM, Jung JH, Park KW, et al. Harmonizing Optimal Strategy for Treatment of coronary artery diseases--comparison of REDUCtion of prasugrEl dose or POLYmer TECHnology in ACS patients (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS RCT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015; 16:409. PMID: 26374625.

Article62. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Cho YH, et al. Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the TICO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020; 323:2407–2416. PMID: 32543684.63. Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. Effect of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy vs dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SMART-CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019; 321:2428–2437. PMID: 31237645.64. Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. 6-month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018; 391:1274–1284. PMID: 29544699.65. Lee CW, Ahn JM, Park DW, et al. Optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2014; 129:304–312. PMID: 24097439.66. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Kim HS, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 12 months versus for 12 months after drug-eluting stents for acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2020; 75:66–73. PMID: 31561932.

Article67. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, et al. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1791–1800. PMID: 25773268.

Article68. Jeong YH, Smith SC Jr, Gurbel PA. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:1273–1274. PMID: 26398082.

Article69. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1319–1330. PMID: 28844192.70. Jeong YH, Bae JS, Gurbel PA. Rivaroxaban in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:396. PMID: 29372978.

Article71. Mo C, Sun G, Lu ML, et al. Proton pump inhibitors in prevention of low-dose aspirin-associated upper gastrointestinal injuries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:5382–5392. PMID: 25954113.

Article72. Kim MS, Song HJ, Lee J, Yang BR, Choi NK, Park BJ. Effectiveness and safety of clopidogrel co-administered with statins and proton pump inhibitors: a Korean National Health Insurance Database Study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019; 106:182–194. PMID: 30648733.

Article73. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010; 376:1670–1681. PMID: 21067804.74. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 73:3168–3209. PMID: 30423391.75. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:111–188. PMID: 31504418.76. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387–2397. PMID: 26039521.77. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:1713–1722. PMID: 28304224.

Article78. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:2097–2107. PMID: 30403574.79. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:1495–1504. PMID: 15007110.

Article80. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2195–2207. PMID: 18997196.

Article81. Robinson JG, Smith B, Maheshwari N, Schrott H. Pleiotropic effects of statins: benefit beyond cholesterol reduction? A meta-regression analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1855–1862. PMID: 16286171.82. Lee KH, Jeong MH, Kim HM, et al. Benefit of early statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction who have extremely low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1664–1671. PMID: 21982310.

Article83. Piao ZH, Jin L, Kim JH, et al. Benefits of statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction with serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≤ 50 mg/dl. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 120:174–180. PMID: 28532771.84. Kim MC, Ahn Y, Cho JY, et al. Benefit of early statin initiation within 48 hours after admission in statin-naïve patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:419–433. PMID: 30808084.

Article85. Ji MS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, et al. Clinical outcome of statin plus ezetimibe versus high-intensity statin therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction propensity-score matching analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 225:50–59. PMID: 27710803.

Article86. Wang P. Statin dose in Asians: is pharmacogenetics relevant? Pharmacogenomics. 2011; 12:1605–1615. PMID: 22044416.

Article87. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:2889–2934. PMID: 24239923.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pharmacotherapy for acute myocardial infarction

- Invasive Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction: What is the Optimal Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction?

- Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon Leads to ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction

- Serum Myoglobin in the Early Phase of Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Myocardial fractional flow reserve in acute myocardial infarction