J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2020 May;63(3):346-357. 10.3340/jkns.2020.0039.

Retethering : A Neurosurgical Viewpoint

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Seoul National University Children’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Anatomy, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Division of Pediatric Urology, Seoul National University Children’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2501722

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2020.0039

Abstract

- During the follow-up period after surgery for spinal dysraphism, a certain portion of patients show neurological deterioration and its secondary phenomena, such as motor, sensory or sphincter changes, foot and spinal deformities, pain, and spasticity. These clinical manifestations are caused by tethering effects on the neural structures at the site of previous operation. The widespread recognition of retethering drew the attention of medical professionals of various specialties because of its incidence, which is not low when surveillance is adequate, and its progressive nature. This article reviews the literature on the incidence and timing of deterioration, predisposing factors for retethering, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, surgical treatment and its complications, clinical outcomes, prognostic factors after retethering surgery and preventive measures of retethering. Current practice and opinions of Seoul National University Children’s Hospital team were added in some parts. The literature shows a wide range of data regarding the incidence, rate and degree of surgical complications and long-term outcomes. The method of prevention is still one of the main topics of this entity. Although alternatives such as spinal column shortening were introduced, re-untethering by conventional surgical methods remains the current main management tool. Re-untethering surgery is a much more difficult task than primary untethering surgery. Updated publications include strong skepticism on re-untethering surgery in a certain group of patients, though it is from a minority of research groups. For all of the abovementioned reasons, new information and ideas on the early diagnosis, treatment and prevention of retethering are critically necessary in this era.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Disorders of Secondary Neurulation : Mainly Focused on Pathoembryogenesis

Jeyul Yang, Ji Yeoun Lee, Kyung Hyun Kim, Kyu-Chang Wang

J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2021;64(3):386-405. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2021.0023.

Reference

-

References

1. Abrahamsson K, Olsson I, Sillén U. Urodynamic findings in children with myelomeningocele after untethering of the spinal cord. J Urol. 177:331–334. discussion 334. 2007.

Article2. Aldave G, Hansen D, Hwang SW, Moreno A, Briceño V, Jea A. Spinal column shortening for tethered cord syndrome associated with myelomeningocele, lumbosacral lipoma, and lipomyelomeningocele in children and young adults. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 19:703–710. 2017.

Article3. Al-Holou WN, Muraszko KM, Garton HJ, Buchman SR, Maher CO. The outcome of tethered cord release in secondary and multiple repeat tethered cord syndrome. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 4:28–36. 2009.

Article4. Alzahrani A, Alsowayan O, Farmer JP, Capolicchio JP, Jednak R, ElSherbiny M. Comprehensive analysis of the clinical and urodynamic outcomes of secondary tethered spinal cord before and after spinal cord untethering. J Pediatr Urol. 12:101.e1–e6. 2016.

Article5. Blount JP, Tubbs RS, Okor M, Tyler-Kabara EC, Wellons JC 3rd, Grabb PA, et al. Supraplacode spinal cord transection in paraplegic patients with myelodysplasia and repetitive symptomatic tethered spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 103(1 Suppl):36–39. 2005.

Article6. Bowman RM, Mohan A, Ito J, Seibly JM, McLone DG. Tethered cord release: a long-term study in 114 patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 3:181–187. 2009.

Article7. Bragg TM, Iskandar BJ. Lipomyelomeningocele. In : Winn HR, editor. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery, ed 7. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2017. 2:p. 1834–1841.8. Cochrane DD. Cord untethering for lipomyelomeningocele : expectation after surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 23:E9. 2007.9. Cohrs G, Drucks B, Sürie JP, Vokuhl C, Synowitz M, Held-Feindt J, et al. Expression profiles of pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic mediators in secondary tethered cord syndrome after myelomeningocele repair surgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 35:315–328. 2019.

Article10. Colak A, Pollack IF, Albright AL. Recurrent tethering: a common long-term problem after lipomyelomeningocele repair. Pediatr Neurosurg. 29:184–190. 1998.

Article11. Cornips EM, Razenberg FG, van Rhijn LW, Soudant DL, van Raak EP, Weber JW, et al. The lumbosacral angle does not reflect progressive tethered cord syndrome in children with spinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 26:1757–1764. 2010.

Article12. Faggin R, Drigo P, Denaro L, Sartori S, d’Avella D. Hydromyelia associated with spinal lipoma of the conus: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 35:E1069–E1071. 2010.13. Garces J, Mathkour M, Scullen T, Kahn L, Biro E, Pham A, et al. First case of autonomic dysreflexia following elective lower thoracic spinal cord transection in a spina bifida adult. World Neurosurg. 108:988.e1–988.e5. 2017.

Article14. George TM, Fagan LH. Adult tethered cord syndrome in patients with postrepair myelomeningocele: an evidence-based outcome study. J Neurosurg. 102(2 Suppl):150–156. 2005.

Article15. Goodrich DJ, Patel D, Loukas M, Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ. Symptomatic retethering of the spinal cord in postoperative lipomyelomeningocele patients : a meta-analysis. Childs Nerv Syst. 32:121–126. 2016.

Article16. Grande AW, Maher PC, Morgan CJ, Choutka O, Ling BC, Raderstorf TC, et al. Vertebral column subtraction osteotomy for recurrent tethered cord syndrome in adults : a cadaveric study. J Neurosurg Spine. 4:478–484. 2006.

Article17. Haberl H, Tallen G, Michael T, Hoffmann K, Benndorf G, Brock M. Surgical aspects and outcome of delayed tethered cord release. Zentralbl Neurochir. 65:161–167. 2004.

Article18. Hayashi T, Takemoto J, Ochiai T, Kimiwada T, Shirane R, Sakai K, et al. Surgical indication and outcome in patients with postoperative retethered cord syndrome. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 11:133–139. 2013.

Article19. Herman JM, McLone DG, Storrs BB, Dauser RC. Analysis of 153 patients with myelomeningocele or spinal lipoma reoperated upon for a tethered cord. Pediatr Neurosurg. 19:243–249. 1993.

Article20. Kanno H, Aizawa T, Ozawa H, Hoshikawa T, Itoi E, Kokubun S. Spineshortening vertebral osteotomy in a patient with tethered cord syndrome and a vertebral fracture. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 9:62–66. 2008.

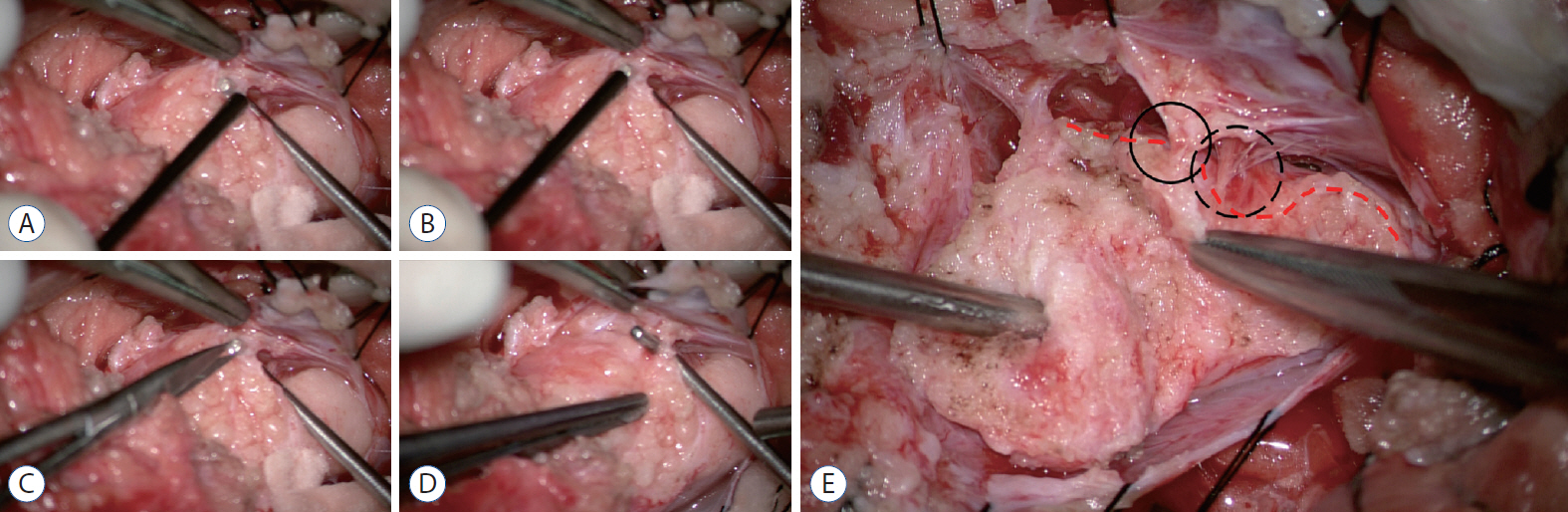

Article21. Kim KH, Chong S, Lee JY, Kim SK, Cho BK, Wang KC. A Method of untethering by skipping the area of positive responses on electrical stimulation during surgery of lumbosacral lipomatous malformation : “hopping on a stepping stone”. World Neurosurg. 124:48–51. 2019.

Article22. Kokubun S, Ozawa H, Aizawa T, Ly NM, Tanaka Y. Spine-shortening osteotomy for patients with tethered cord syndrome caused by lipomyelomeningocele. J Neurosurg Spine. 15:21–27. 2011.

Article23. Lam WW, Ai V, Wong V, Lui WM, Chan FL, Leong L. Ultrasound measurement of lumbosacral spine in children. Pediatr Neurol. 30:115–121. 2004.

Article24. Lee JY, Phi JH, Cheon JE, Kim SK, Kim IO, Cho BK, et al. Preuntethering and postuntethering courses of syringomyelia associated with tethered spinal cord. Neurosurgery. 71:23–29. 2012.

Article25. Lin W, Xu H, Duan G, Xie J, Chen Y, Jiao B, et al. Spine-shortening osteotomy for patients with tethered cord syndrome : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Res. 40:340–363. 2018.

Article26. Maher CO, Goumnerova L, Madsen JR, Proctor M, Scott RM. Outcome following multiple repeated spinal cord untethering operations. J Neurosurg. 106(6 Suppl):434–438. 2007.

Article27. Martínez-Lage JF, Ruiz-Espejo Vilar A, Almagro MJ, Sánchez del Rincón I, Ros de San Pedro J, Felipe-Murcia M, et al. Spinal cord tethering in myelomeningocele and lipomeningocele patients: the second operation. Neurocirugia (Astur). 18:312–319. 2007.28. Mehta VA, Bettegowda C, Ahmadi SA, Berenberg P, Thomale UW, Haberl EJ, et al. Spinal cord tethering following myelomeningocele repair. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 6:498–505. 2010.

Article29. Mehta VA, Gottfried ON, McGirt MJ, Gokaslan ZL, Ahn ES, Jallo GI. Safety and efficacy of concurrent pediatric spinal cord untethering and deformity correction. J Spinal Disord Tech. 24:401–405. 2011.

Article30. Meyrat BJ, Tercier S, Lutz N, Rilliet B, Forcada-Guex M, Vernet O. Introduction of a urodynamic score to detect pre- and postoperative neurological deficits in children with a primary tethered cord. Childs Nerv Syst. 19:716–721. 2003.

Article31. Ogiwara H, Lyszczarz A, Alden TD, Bowman RM, McLone DG, Tomita T. Retethering of transected fatty filum terminales. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 7:42–46. 2011.

Article32. Ostling LR, Bierbrauer KS, Kuntz C 4th. Outcome, reoperation, and complications in 99 consecutive children operated for tight or fatty filum. World Neurosurg. 77:187–191. 2012.

Article33. Pang D, Zovickian J, Oviedo A. Long-term outcome of total and neartotal resection of spinal cord lipomas and radical reconstruction of the neural placode, part II : outcome analysis and preoperative profiling. Neurosurgery. 66:253–272. discussion 272-273. 2010.34. Pierre-Kahn A, Zerah M, Renier D, Cinalli G, Sainte-Rose C, LellouchTubiana A, et al. Congenital lumbosacral lipomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 13:298–334. discussion 335. 1997.

Article35. Safain MG, Burke SM, Riesenburger RI, Zerris V, Hwang SW. The effect of spinal osteotomies on spinal cord tension and dural buckling: a cadaveric study. J Neurosurg Spine. 23:120–127. 2015.

Article36. Samuels R, McGirt MJ, Attenello FJ, Garcés Ambrossi GL, Singh N, Solakoglu C, et al. Incidence of symptomatic retethering after surgical management of pediatric tethered cord syndrome with or without duraplasty. Childs Nerv Syst. 25:1085–1089. 2009.

Article37. Schumacher R, Richter D. One-dimensional fourier transformation of M-mode sonograms for frequency analysis of moving structures with application to spinal cord motion. Pediatr Radiol. 34:793–797. 2004.

Article38. Segal LS, Czoch W, Hennrikus WL, Wade Shrader M, Kanev PM. The spectrum of musculoskeletal problems in lipomyelomeningocele. J Child Orthop. 7:513–519. 2013.

Article39. Sharma U, Pal K, Pratap A, Gupta DK, Jagannathan NR. Potential of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the evaluation of patients with tethered cord syndrome following surgery. J Neurosurg. 105(5 Suppl):396–402. 2006.

Article40. Stamates MM, Frim DM, Yang CW, Katzman GL, Ali S. Magnetic resonance imaging in the prone position and the diagnosis of tethered spinal cord. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 21:4–10. 2018.

Article41. Sun J, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wang Y, Yang Y, Kong Q, et al. Clinical outcomes of primary and revision untethering surgery in patients with tethered cord syndrome and spinal bifida. World Neurosurg. 116:e66–e70. 2018.

Article42. Tarcan T, Bauer S, Olmedo E, Khoshbin S, Kelly M, Darbey M. Long-term followup of newborns with myelodysplasia and normal urodynamic findings : is followup necessary? J Urol. 165:564–567. 2001.

Article43. Thuy M, Chaseling R, Fowler A. Spinal cord detethering procedures in children: a 5 year retrospective cohort study of the early post-operative course. J Clin Neurosci. 22:838–842. 2015.

Article44. Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ. A simple method to deter retethering in patients with spinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 22:715–716. 2006.

Article45. Vassilyadi M, Tataryn Z, Merziotis M. Retethering in children after sectioning of the filum terminale. Pediatr Neurosurg. 48:335–341. 2012.

Article46. Walker CT, Godzik J, Kakarla UK, Turner JD, Whiting AC, Nakaji P. Human amniotic membrane for the prevention of intradural spinal cord adhesions: retrospective review of its novel use in a case series of 14 patients. Neurosurgery. 83:989–996. 2018.

Article47. Yong RL, Habrock-Bach T, Vaughan M, Kestle JR, Steinbok P. Symptomatic retethering of the spinal cord after section of a tight filum terminale. Neurosurgery. 68:1594–1601. discussion 1601-1602. 2011.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Tethered Cord Syndrome ; Surgical Indication, Technique and Outcome

- What Do You Think about the Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society?: Survey of Korean Neurosurgical Society Members

- Surgical Treatment of Foot Deformities in Myelodysplasia

- Essentials of Neurosurgical Procedures and Operations Published by Korean Neurosurgical Society

- Functional Cosmetics from a Medical Viewpoint