Intest Res.

2019 Oct;17(4):496-503. 10.5217/ir.2019.00050.

Polypharmacy is a risk factor for disease flare in adult patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA. bwb2c@virginia.edu

- KMID: 2465815

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2019.00050

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/AIMS

Polypharmacy is a common clinical problem with chronic diseases that can be associated with adverse patient outcomes. The present study aimed to determine the prevalence and patient-specific characteristics associated with polypharmacy in an ulcerative colitis (UC) population and to assess the impact of polypharmacy on disease outcomes.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of patients with UC who visited a tertiary medical center outpatient clinic between 2006 and 2011 was performed. Polypharmacy was defined as major ( ≥ 5 non-UC medications) or minor (2-4 non-UC medications). UC medications were excluded in the polypharmacy grouping to minimize the confounding between disease severity and polypharmacy. Outcomes of interest include disease flare, therapy escalation, UC-related hospitalization, and surgery within 5 years of the initial visit.

RESULTS

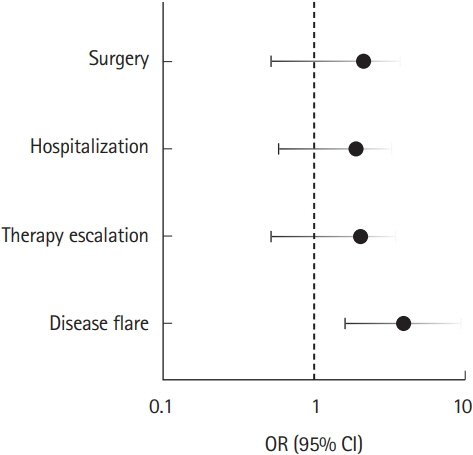

A total of 457 patients with UC were eligible for baseline analysis. Major polypharmacy was identified in 29.8% of patients, and minor polypharmacy was identified in 40.9% of the population. Polypharmacy at baseline was associated with advanced age (P< 0.001), female sex (P= 0.019), functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders (P< 0.001), and psychiatric disease (P< 0.001). Over 5 years of follow-up, 265 patients remained eligible for analysis. After adjusting for age, sex, functional GI disorders, and psychiatric disease, major polypharmacy was found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of disease flare (odds ratio, 4.00; 95% confidence interval, 1.66-9.62). However, major polypharmacy was not associated with the risk of therapy escalation, hospitalization, or surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Polypharmacy from non-inflammatory bowel disease medications was present in a substantial proportion of adult patients with UC and was associated with an increased risk of disease flare.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:2066–2078.

Article2. Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 12:205–217.3. Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98:1064–1072.

Article4. Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:1882–1889.

Article5. Loftus EV Jr, Guérin A, Yu AP, et al. Increased risks of developing anxiety and depression in young patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:1670–1677.6. Cross RK, Wilson KT, Binion DG. Narcotic use in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; 100:2225–2229.7. Ha C, Magowan S, Accortt NA, Chen J, Stone CD. Risk of arterial thrombotic events in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:1445–1451.8. Terzić J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2101–2114.9. Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Blanchard JF. The clustering of other chronic inflammatory diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005; 129:827–836.10. Haapamäki J, Roine RP, Turunen U, Färkkilä MA, Arkkila PE. Increased risk for coronary heart disease, asthma, and connective tissue diseases in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011; 5:41–47.

Article11. Ha CY. Medical management of inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly: balancing safety and efficacy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014; 30:67–78.12. Hovstadius B, Petersson G. Factors leading to excessive polypharmacy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012; 28:159–172.13. Juneja M, Baidoo L, Schwartz MB, et al. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57:2408–2415.14. Buckley JP, Kappelman MD, Allen JK, Van Meter SA, Cook SF. The burden of comedication among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:2725–2736.15. Sergi G, De Rui M, Sarti S, Manzato E. Polypharmacy in the elderly: can comprehensive geriatric assessment reduce inappropriate medication use? Drugs Aging. 2011; 28:509–518.16. Cross RK, Wilson KT, Binion DG. Polypharmacy and Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 21:1211–1216.

Article17. Bjerrum L, Søgaard J, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen. A prescription database study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998; 54:197–202.18. Viktil KK, Enstad M, Kutschera J, Smedstad LM, Schjøtt J. Polypharmacy among patients admitted to hospital with rheumatic diseases. Pharm World Sci. 2001; 23:153–158.19. Perry BA, Turner LW. A prediction model for polypharmacy: are older, educated women more susceptible to an adverse drug event? J Women Aging. 2001; 13:39–51.20. Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003; 289:1107–1116.21. Kim S, Bennett K, Wallace E, Fahey T, Cahir C. Measuring medication adherence in older community-dwelling patients with multimorbidity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018; 74:357–364.22. Vetrano DL, Bianchini E, Onder G, et al. Poor adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease medications in primary care: role of age, disease burden and polypharmacy. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017; 17:2500–2506.23. Mehat P, Atiquzzaman M, Esdaile JM, AviÑa-Zubieta A, De Vera MA. Medication nonadherence in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017; 69:1706–1713.24. DeSevo G, Klootwyk J. Pharmacologic issues in management of chronic disease. Prim Care. 2012; 39:345–362.25. Irving PM, Shanahan F, Rampton DS. Drug interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008; 103:207–219.

Article26. Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007; 5:345–351.

Article27. Ham M, Moss AC. Mesalamine in the treatment and maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 5:113–123.28. Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature. 2018; 555:623–628.

Article29. Nugent Z, Singh H, Targownik LE, Strome T, Snider C, Bernstein CN. Predictors of emergency department use by persons with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22:2907–2916.

Article30. Click B, Ramos Rivers C, Koutroubakis IE, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of high healthcare use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22:1442–1449.

Article31. Narula N, Borges L, Steinhart AH, Colombel JF. Trends in narcotic and corticosteroid prescriptions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States ambulatory care setting from 2003 to 2011. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017; 23:868–874.32. Hanson KA, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. Clinical features and outcome of patients with inflammatory bowel disease who use narcotics: a case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009; 15:772–777.33. Byrne G, Rosenfeld G, Leung Y, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 2017:6496727.

Article34. Navabi S, Gorrepati VS, Yadav S, et al. Influences and impact of anxiety and depression in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24:2303–2308.35. Goodhand JR, Greig FI, Koodun Y, et al. Do antidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? A retrospective case-matched observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:1232–1239.

Article36. Wahed M, Corser M, Goodhand JR, Rampton DS. Does psychological counseling alter the natural history of inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010; 16:664–669.37. Takeuchi K, Smale S, Premchand P, et al. Prevalence and mechanism of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced clinical relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4:196–202.

Article38. Bonner GF. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with use of celecoxib. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001; 96:1306–1308.39. Meyer AM, Ramzan NN, Heigh RI, Leighton JA. Relapse of inflammatory bowel disease associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Dig Dis Sci. 2006; 51:168–172.40. Evans JM, McMahon AD, Murray FE, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with emergency admission to hospital for colitis due to inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1997; 40:619–622.

Article41. Bonner GF, Walczak M, Kitchen L, Bayona M. Tolerance of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000; 95:1946–1948.

Article42. Bonner GF, Fakhri A, Vennamaneni SR. A long-term cohort study of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and disease activity in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004; 10:751–757.

Article43. Sandborn WJ, Stenson WF, Brynskov J, et al. Safety of celecoxib in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission: a randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4:203–211.

Article44. Hueber W, Patel DD, Dryja T, et al. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med. 2010; 2:52–ra72.

Article45. Miao XP, Ouyang Q, Li HY, Wen ZH, Zhang DK, Cui XY. Role of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2008; 69:181–191.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Seasonal Variation in Flares of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Korean Population

- A Case of Malignant Lymphoma in Patient with Ulcerative Colitis

- A Case of Cytomegalvirus Colitis Developed during the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis

- Clostridioides Infection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Malignant change of chronic ulcerative colitis : report of a case