Infect Chemother.

2019 Sep;51(3):284-294. 10.3947/ic.2019.51.3.284.

Antibiotic Treatment of Vertebral Osteomyelitis caused by Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: A Focus on the Use of Oral β-lactams

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Chung-Ang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Division of Infectious Diseases, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea.

- 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 6Division of Infectious Diseases, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 7Division of Infectious Diseases, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea.

- 8Division of Infectious Diseases, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 9Division of Infectious Diseases, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital, Seoul, Korea. kimbn@paik.ac.kr

- KMID: 2459044

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2019.51.3.284

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Vertebral osteomyelitis (VO) is a rare but serious condition, and a potentially significant cause of morbidity. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) is the most common microorganism in native VO. Long-term administration of parenteral and oral antibiotics with good bioavailability and bone penetration is required for therapy. Use of oral β-lactams against staphylococcal bone and joint infections in adults is not generally recommended, but some experts recommend oral switching with β-lactams. This study aimed to describe the current status of antibiotic therapy and treatment outcomes of oral switching with β-lactams in patients with MSSA VO, and to assess risk factors for treatment failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

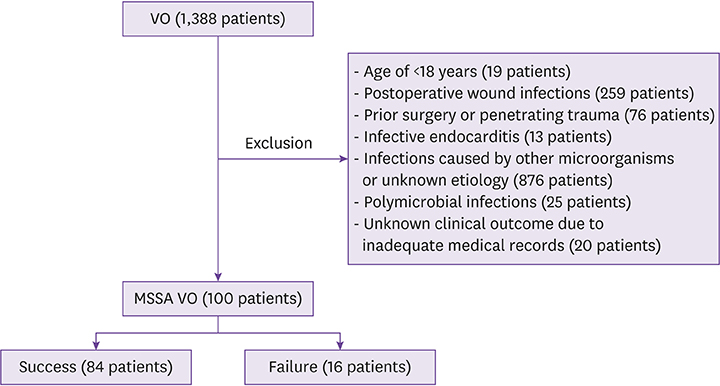

This retrospective study included adult patients with MSSA VO treated at nine university hospitals in Korea between 2005 and 2014. Treatment failure was defined as infection-related death, microbiological relapse, neurologic deficits, or unplanned surgical procedures. Clinical characteristics and antibiotic therapy in the treatment success and treatment failure groups were compared. Risk factors for treatment failure were identified using the Cox proportional hazards model.

RESULTS

A total of 100 patients with MSSA VO were included. All patients were treated, initially or during antibiotic therapy, with one or more parenteral antibiotics. Sixty-nine patients received one or more oral antibiotics. Antibiotic regimens were diverse and durations of parenteral and oral therapy differed, depending on the patient and the hospital. Forty-two patients were treated with parenteral and/or oral β-lactams for a total duration of more than 2 weeks. Compared with patients receiving parenteral β-lactams only, no significant difference in success rates was observed in patients who received oral β-lactams for a relatively long period. Sixteen patients had treatment failure. Old age (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 5.600, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.402 - 22.372, P = 0.015) and failure to improve C-reactive protein levels at follow-up (adjusted HR 3.388, 95% CI 1.168 - 9.829, P = 0.025) were independent risk factors for treatment failure.

CONCLUSION

In the study hospitals, diverse combinations of antibiotics and differing durations of parenteral and oral therapy were used. Based on the findings of this study, we think that switching to oral β-lactams may be safe in certain adult patients with MSSA VO. Since limited data are available on the efficacy of oral antibiotics for treatment of staphylococcal VO in adults, further evaluation of the role of oral switch therapy with β-lactams is needed.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Administration, Oral

Adult

Anti-Bacterial Agents

beta-Lactams

Biological Availability

C-Reactive Protein

Follow-Up Studies

Hospitals, University

Humans

Joints

Korea

Neurologic Manifestations

Osteomyelitis*

Proportional Hazards Models

Recurrence

Retrospective Studies

Risk Factors

Staphylococcus aureus*

Staphylococcus*

Treatment Failure

Treatment Outcome

Anti-Bacterial Agents

C-Reactive Protein

beta-Lactams

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Cefazolin Inoculum Effect and the Presence of type A blaZ Gene according to agr Genotype in Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia

Soon Ok Lee, Shinwon Lee, Sohee Park, Jeong Eun Lee, Sun Hee Lee

Infect Chemother. 2019;51(4):376-385. doi: 10.3947/ic.2019.51.4.376.

Reference

-

1. Zimmerli W. Clinical practice. Vertebral osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:1022–1029.2. Issa K, Diebo BG, Faloon M, Naziri Q, Pourtaheri S, Paulino CB, Emami A. The epidemiology of vertebral osteomyelitis in the United States from 1998 to 2013. Clin Spine Surg. 2018; 31:E102–E108.

Article3. Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 39:10–17.

Article4. Gupta A, Kowalski TJ, Osmon DR, Enzler M, Steckelberg JM, Huddleston PM, Nassr A, Mandrekar JM, Berbari EF. Long-term outcome of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a cohort study of 260 patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014; 1:ofu107.

Article5. McHenry MC, Easley KA, Locker GA. Vertebral osteomyelitis: long-term outcome for 253 patients from 7 Cleveland-area hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002; 34:1342–1350.

Article6. Chang WS, Ho MW, Lin PC, Ho CM, Chou CH, Lu MC, Chen YJ, Chen HT, Wang JH, Chi CY. Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis, 12-year experience from a tertiary hospital in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018; 51:235–242.

Article7. Park KH, Kim DY, Lee YM, Lee MS, Kang KC, Lee JH, Park SY, Moon C, Chong YP, Kim SH, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim YS, Woo JH, Ryu BH, Bae IG, Cho OH. Selection of an appropriate empiric antibiotic regimen in hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. PLoS One. 2019; 14:e0211888.

Article8. Bernard L, Dinh A, Ghout I, Simo D, Zeller V, Issartel B, Le Moing V, Belmatoug N, Lesprit P, Bru JP, Therby A, Bouhour D, Dénes E, Debard A, Chirouze C, Fèvre K, Dupon M, Aegerter P, Mulleman D. Duration of Treatment for Spondylodiscitis (DTS) study group. Antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks versus 12 weeks in patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015; 385:875–882.

Article9. Park KH, Cho OH, Lee JH, Park JS, Ryu KN, Park SY, Lee YM, Chong YP, Kim SH, Lee SO, Choi SH, Bae IG, Kim YS, Woo JH, Lee MS. Optimal duration of antibiotic therapy in patients with hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis at low risk and high risk of recurrence. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 62:1262–1269.

Article10. Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, Darouiche RO, Widmer AF, Schmitt SK, Hendershot EF, Holtom PD, Huddleston PM 3rd, Petermann GW, Osmon DR. Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 61:e26–46.11. Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004; 364:369–379.

Article12. Rao N, Ziran BH, Lipsky BA. Treating osteomyelitis: antibiotics and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127:Suppl 1. 177S–187S.

Article13. Davis JS. Management of bone and joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus . Intern Med J. 2005; 35:Suppl 2. S79–S96.14. Haas DW, McAndrew MP. Bacterial osteomyelitis in adults: evolving considerations in diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med. 1996; 101:550–561.

Article15. Loibl M, Stoyanov L, Doenitz C, Brawanski A, Wiggermann P, Krutsch W, Nerlich M, Oszwald M, Neumann C, Salzberger B, Hanses F. Outcome-related co-factors in 105 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis in a tertiary care hospital. Infection. 2014; 42:503–510.

Article16. Yoon SH, Chung SK, Kim KJ, Kim HJ, Jin YJ, Kim HB. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: identification of microorganism and laboratory markers used to predict clinical outcome. Eur Spine J. 2010; 19:575–582.

Article17. Kowalski TJ, Berbari EF, Huddleston PM, Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR. Do follow-up imaging examinations provide useful prognostic information in patients with spine infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:172–179.

Article18. Solis Garcia del Pozo J, Vives Soto M, Solera J. Vertebral osteomyelitis: long-term disability assessment and prognostic factors. J Infect. 2007; 54:129–134.

Article19. Peltola H, Pääkkönen M. Acute osteomyelitis in children. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:352–360.

Article20. DeRonde KJ, Girotto JE, Nicolau DP. Management of pediatric acute hematogenous osteomyelitis, Part I: Antimicrobial stewardship approach and review of therapies for Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Kingella kingae. Pharmacotherapy. 2018; 38:947–966.

Article21. Le Saux N. Diagnosis and management of acute osteoarticular infections in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2018; 23:336–343.

Article22. Korean Society for Chemotherapy. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Korean Orthopaedic Association. Clinical guidelines for the antimicrobial treatment of bone and joint infections in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2014; 46:125–138.23. Daver NG, Shelburne SA, Atmar RL, Giordano TP, Stager CE, Reitman CA, White AC Jr. Oral step-down therapy is comparable to intravenous therapy for Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. J Infect. 2007; 54:539–544.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Oral Agents for the Treatment of Orthopedic Infections Caused by Methicillin-resistant Staphylococci

- Panton-Valentine Leukocidin Positive Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: A Case Report of Two Pediatric Patients with Thrombotic Complications

- A case of multiple furunculosis caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococcs aureus

- Microbiological Characteristics of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- Detection of Multidrug Resistant Patterns and Associated - genes of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ( MRSA ) Isolated from Clinical Specimens