Korean Circ J.

2019 Aug;49(8):691-708. 10.4070/kcj.2019.0187.

Metabolic Syndrome in Adult Congenital Heart Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cardiovascular Center, Department of Cardiology, St. Luke's International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. koniwa@luke.or.jp, kniwa@aol.com

- KMID: 2456864

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0187

Abstract

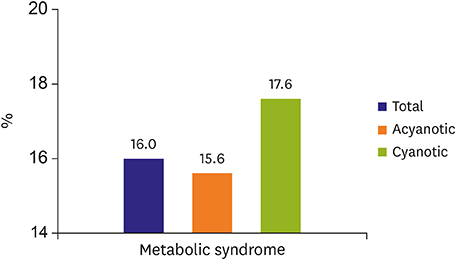

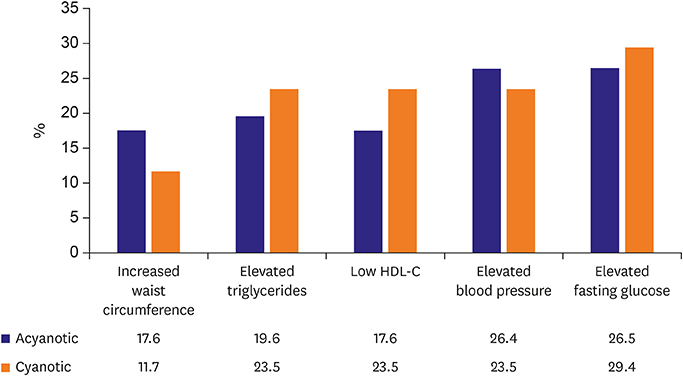

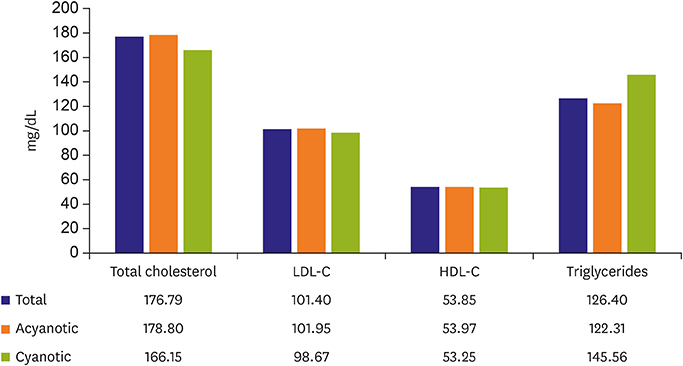

- In adult congenital heart disease (ACHD), residua and sequellae after initial repair develop late complications such as cardiac failure, arrhythmias, thrombosis, aortopathy, pulmonary hypertension and others. Acquired lesions with aging such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity can be negative influence on original cardiovascular disease (CVD). Also, atherosclerosis may pose an additional health problem to ACHD when they grow older and reach the age at which atherosclerosis becomes clinically relevant. In spite of the theoretical risk of atherosclerosis in ACHD due to above mentioned factors, cyanotic ACHDs even after repair are noted to have minimal incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD). Acyanotic ACHD has similar prevalence of CAD as the general population. However, even in cyanotic ACHD, CAD can develop when they have several risk factors for CAD. The prevalence of risk factor is similar between ACHD and the general population. Risk of premature atherosclerotic CVD in ACHD is based, 3 principal mechanisms: lesions with coronary artery abnormalities, obstructive lesions of left ventricle and aorta such as coarctation of the aorta and aortopathy. Coronary artery abnormalities are directly affected or altered surgically, such as arterial switch in transposition patients, may confer greater risk for premature atherosclerotic CAD. Metabolic syndrome is more common among ACHD than in the general population, and possibly increases the incidence of atherosclerotic CAD even in ACHD in future. Thus, ACHD should be screened for metabolic syndrome and eliminating risk factors for atherosclerotic CAD.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Risk Stratification Models for Adults with Congenital Heart Disease

Han Ki Park

Korean Circ J. 2019;49(9):864-865. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2019.0259.Sexual Health Issue in Adult Congenital Heart Disease to Improve the Quality of Life

Se Yong Jung, Jae Young Choi

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(3):243-245. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0018.Prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease and Metabolic Syndrome in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease

Shin Yi Jang, Eun Kyoung Kim, Sung-A Chang, June Huh, Jinyoung Song, I-Seok Kang, Seung Woo Park

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(45):e375. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e375.

Reference

-

1. Niwa K. Adults with congenital heart disease transition. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015; 27:576–580.

Article2. Perloff JK. The coronary circulation in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2004; 97:Suppl 1. 79–86.

Article3. Giannakoulas G, Dimopoulos K, Engel R, et al. Burden of coronary artery disease in adults with congenital heart disease and its relation to congenital and traditional heart risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 103:1445–1450.4. Yalonetsky S, Horlick EM, Osten MD, Benson LN, Oechslin EN, Silversides CK. Clinical characteristics of coronary artery disease in adults with congenital heart defects. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 164:217–220.

Article5. Zaidi AN, Bauer JA, Michalsky MP, et al. The impact of obesity on early postoperative outcomes in adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011; 6:241–246.

Article6. Moons P, Van Deyk K, Dedroog D, Troost E, Budts W. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006; 13:612–616.

Article7. Pemberton VL, McCrindle BW, Barkin S, et al. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Working Group on obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2010; 121:1153–1159.

Article8. Duffels MG, Mulder KM, Trip MD, et al. Atherosclerosis in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circ J. 2010; 74:1436–1441.

Article9. Niwa K. The coronary circulation in adults with congenital heart disease. Intern Med. 2006; 45:1199–1200.

Article10. Perloff JK. Cyanotic congenital heart disease the coronary arterial circulation. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012; 8:1–5.11. Fyfe A, Perloff JK, Niwa K, Child JS, Miner PD. Cyanotic congenital heart disease and coronary artery atherogenesis. Am J Cardiol. 2005; 96:283–290.

Article12. Chugh R, Perloff JK, Fishbein M, Child JS. Extramural coronary arteries in adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 94:1355–1357.

Article13. Malinski T. Normal and pathological distribution of nitric oxide in the cardiovascular system. Pol J Pharmacol. 1998; 50:387–391.14. Koller A, Sun D, Kaley G. Role of shear stress and endothelial prostaglandins in flow- and viscosity-induced dilation of arterioles in vitro. Circ Res. 1993; 72:1276–1284.

Article15. Niwa K, Perloff JK, Bhuta SM, et al. Structural abnormalities of great arterial walls in congenital heart disease: light and electron microscopic analyses. Circulation. 2001; 103:393–400.16. Hamada H, Ebata R, Higashi K, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor in cyanotic congenital heart disease functionally contributes to endothelial cell kinetics in vitro. Int J Cardiol. 2007; 120:66–71.

Article17. Arias-Stella J, Topilsky M. Anatomy of the coronary artery circulation at high altitude in high altitude physiology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Publishers;1971. p. 149–157.18. European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. Reiner Z, Catapano AL, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1769–1818.19. Tarp JB, Sørgaard MH, Christoffersen C, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2019; 277:97–103.

Article20. Niwa K. Coronary artery anomalies and coronary artery disease in adults with congenital cardiac disease. Asia Pac Cardiol. 2007; 1:70–72.

Article21. Gross SS, Lane P. Physiological reactions of nitric oxide and hemoglobin: a radical rethink. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; 96:9967–9969.

Article22. Niwa K, Perloff JK, Kaplan S, Child JS, Miner PD. Eisenmenger syndrome in adults: ventricular septal defect, truncus arteriosus, univentricular heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 34:223–232.23. Madhavan M, Wattigney WA, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Serum bilirubin distribution and its relation to cardiovascular risk in children and young adults. Atherosclerosis. 1997; 131:107–113.

Article24. Lill MC, Perloff JK, Child JS. Pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006; 98:254–258.

Article25. Pasquali SK, Marino BS, Powell DJ, et al. Following the arterial switch operation, obese children have risk factors for early cardiovascular disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010; 5:16–24.

Article26. Niwa K. Pathological background. In : Niwa K, Kaemmerer H, editors. Aortopathy. Tokyo: Springer;2017. p. 15–30.27. Niwa K. Landmark lecture: Perloff lecture: Tribute to Professor Joseph Kayle Perloff and lessons learned from him: aortopathy in adults with CHD. Cardiol Young. 2017; 27:1959–1965.

Article28. Niwa K. Aortopathy in congenital heart disease in adults: aortic dilatation with decreased aortic elasticity that impacts negatively on left ventricular function. Korean Circ J. 2013; 43:215–220.

Article29. Click RL, Holmes DR Jr, Vlietstra RE, Kosinski AS, Kronmal RA. Anomalous coronary arteries: location, degree of atherosclerosis and effect on survival--a report from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989; 13:531–537.

Article30. Pedra SR, Pedra CA, Abizaid AA, et al. Intracoronary ultrasound assessment late after the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:2061–2068.

Article31. Gagliardi MG, Adorisio R, Crea F, Versacci P, Di Donato R, Sanders SP. Abnormal vasomotor function of the epicardial coronary arteries in children five to eight years after arterial switch operation: an angiographic and intracoronary Doppler flow wire study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1565–1572.32. Pasquali SK, Marino BS, Pudusseri A, et al. Risk factors and comorbidities associated with obesity in children and adolescents after the arterial switch operation and Ross procedure. Am Heart J. 2009; 158:473–479.

Article33. Basso C, Maron BJ, Corrado D, Thiene G. Clinical profile of congenital coronary artery anomalies with origin from the wrong aortic sinus leading to sudden death in young competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1493–1501.

Article34. Roberts WC. Major anomalies of coronary arterial origin seen in adulthood. Am Heart J. 1986; 111:941–963.

Article35. Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Epidemiology and Prevention, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Nursing, and the Kidney in Heart Disease; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2006; 114:2710–2738.36. Vriend JW, van Montfrans GA, Romkes HH, et al. Relation between exercise-induced hypertension and sustained hypertension in adult patients after successful repair of aortic coarctation. J Hypertens. 2004; 22:501–509.

Article37. Gidding SS, Rocchini AP, Moorehead C, Schork MA, Rosenthal A. Increased forearm vascular reactivity in patients with hypertension after repair of coarctation. Circulation. 1985; 71:495–499.

Article38. Beekman RH, Katz BP, Moorehead-Steffens C, Rocchini AP. Altered baroreceptor function in children with systolic hypertension after coarctation repair. Am J Cardiol. 1983; 52:112–117.

Article39. Strafford MA, Griffiths SP, Gersony WM. Coarctation of the aorta: a study in delayed detection. Pediatrics. 1982; 69:159–163.40. Brouwer RM, Erasmus ME, Ebels T, Eijgelaar A. Influence of age on survival, late hypertension, and recoarctation in elective aortic coarctation repair. Including long-term results after elective aortic coarctation repair with a follow-up from 25 to 44 years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994; 108:525–531.41. Freed MD, Rocchini A, Rosenthal A, Nadas AS, Castaneda AR. Exercise-induced hypertension after surgical repair of coarctation of the aorta. Am J Cardiol. 1979; 43:253–258.

Article42. Connolly HM, Huston J 3rd, Brown RD Jr, Warnes CA, Ammash NM, Tajik AJ. Intracranial aneurysms in patients with coarctation of the aorta: a prospective magnetic resonance angiographic study of 100 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003; 78:1491–1499.

Article43. Roberts WC. Anatomically isolated aortic valvular disease. The case against its being of rheumatic etiology. Am J Med. 1970; 49:151–159.44. Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:1561–1566.

Article45. Williams JC, Barratt-Boyes BG, Lowe JB. Supravalvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1961; 24:1311–1318.

Article46. Daniels SR, Loggie JM, Schwartz DC, Strife JL, Kaplan S. Systemic hypertension secondary to peripheral vascular anomalies in patients with Williams syndrome. J Pediatr. 1985; 106:249–251.

Article47. Senzaki H, Iwamoto Y, Ishido H, et al. Arterial haemodynamics in patients after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: influence on left ventricular after load and aortic dilatation. Heart. 2008; 94:70–74.

Article48. Pillutla P, Shetty KD, Foster E. Mortality associated with adult congenital heart disease: trends in the US population from 1979 to 2005. Am Heart J. 2009; 158:874–879.

Article49. Javier AD, Niwa K. Cardiovascular risk factors among adults with congenital heart disease. Nihon Shoni Junkanki Gakkai Zasshi. 2013; 29:S137.50. Deen JF, Krieger EV, Slee AE, et al. Metabolic syndrome in adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e001132.

Article51. Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:1113–1132.52. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001; 285:2486–2497.53. Rhodes J, Curran TJ, Camil L, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on the exercise function of children with serious congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2005; 116:1339–1345.

Article54. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (JP). Results of National health and nutrition survey by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare;Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/kenkou/eiyou/h29-houkoku.html.55. Shustak RJ, McGuire SB, October TW, Phoon CK, Chun AJ. Prevalence of obesity among patients with congenital and acquired heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012; 33:8–14.

Article56. Martinez SC, Byku M, Novak EL, et al. Increased body mass index is associated with congestive heart failure and mortality in adult Fontan patients. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016; 11:71–79.

Article57. Vogt KN, Manlhiot C, Van Arsdell G, Russell JL, Mital S, McCrindle BW. Somatic growth in children with single ventricle physiology impact of physiologic state. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:1876–1883.58. Freud LR, Webster G, Costello JM, et al. Growth and obesity among older single ventricle patients presenting for Fontan conversion. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2015; 6:514–520.

Article59. Chung ST, Hong B, Patterson L, Petit CJ, Ham JN. High overweight and obesity in Fontan patients: a 20-year history. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016; 37:192–200.

Article60. Wellnitz K, Harris IS, Sapru A, Fineman JR, Radman M. Longitudinal development of obesity in the post-Fontan population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015; 69:1105–1108.

Article61. Daniels SR, Kimball TR, Morrison JA, Khoury P, Witt S, Meyer RA. Effect of lean body mass, fat mass, blood pressure, and sexual maturation on left ventricular mass in children and adolescents. Statistical, biological, and clinical significance. Circulation. 1995; 92:3249–3254.62. Maser RE, Lenhard MJ. An overview of the effect of weight loss on cardiovascular autonomic function. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007; 3:204–211.63. Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, Okonko D, et al. Exercise intolerance in adult congenital heart disease: comparative severity, correlates, and prognostic implication. Circulation. 2005; 112:828–835.64. Reybrouck T, Mertens L. Physical performance and physical activity in grown-up congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005; 12:498–502.

Article65. Cohen MS. Clinical practice: the effect of obesity in children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2012; 171:1145–1150.66. Stefan MA, Hopman WM, Smythe JF. Effect of activity restriction owing to heart disease on obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005; 159:477–481.

Article67. Longmuir PE, Brothers JA, de Ferranti SD, et al. Promotion of physical activity for children and adults with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013; 127:2147–2159.68. Owens JL, Musa N. Nutrition support after neonatal cardiac surgery. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009; 24:242–249.

Article69. Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsén TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1802–1809.

Article70. Vieira TC, Trigo M, Alonso RR, et al. Assessment of food intake in infants between 0 and 24 months with congenital heart disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007; 89:219–224.71. Lerman JB, Parness IA, Shenoy RU. Body weights in adults with congenital heart disease and the obesity frequency. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 119:638–642.

Article72. Shiina Y, Matsumoto N, Okamura D, et al. Sarcopenia in adults with congenital heart disease: nutritional status, dietary intake, and resistance training. J Cardiol. 2019; 74:84–89.

Article73. Murakami T, Shiraishi M, Shiina Y, Tateno S, Kawasoe Y, Niwa K. B1-2. High blood pressure in adult patients with congenital heart disease. J Adult Congenit Heart Dis. 2013; 5:99.74. Afilalo J, Therrien J, Pilote L, Ionescu-Ittu R, Martucci G, Marelli AJ. Geriatric congenital heart disease: burden of disease and predictors of mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1509–1515.75. Engelfriet P, Boersma E, Oechslin E, et al. The spectrum of adult congenital heart disease in Europe: morbidity and mortality in a 5 year follow-up period. The Euro Heart Survey on adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:2325–2333.76. Higashi K, Tateno S, Niwa K, et al. Hypocholesterolemia in cyanotic congenital heart disease in children. Nihon Shoni Junkanki Gakkai Zasshi. 2006; 22:432.77. Lui GK, Fernandes S, McElhinney DB. Management of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014; 3:e001076.

Article78. Joffres M, Shields M, Tremblay MS, Connor Gorber S. Dyslipidemia prevalence, treatment, control, and awareness in the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can J Public Health. 2013; 104:e252–e257.

Article79. Martínez-Quintana E, Rodríguez-González F. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations in adult congenital heart disease patients. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014; 9:63–68.

Article80. Martínez-Quintana E, Rodríguez-González F, Nieto-Lago V, Nóvoa FJ, López-Rios L, Riaño-Ruiz M. Serum glucose and lipid levels in adult congenital heart disease patients. Metabolism. 2010; 59:1642–1648.

Article81. Ohuchi H, Miyamoto Y, Yamamoto M, et al. High prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism in young adult patients with complex congenital heart disease. Am Heart J. 2009; 158:30–39.

Article82. Dellborg M, Björk A, Pirouzi Fard MN, et al. High mortality and morbidity among adults with congenital heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2015; 49:344–350.83. Ohuchi H, Yasuda K, Ono S, et al. Low fasting plasma glucose level predicts morbidity and mortality in symptomatic adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 174:306–312.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Three cases of asplenia syndrome associated with congenital heart disease

- Differential Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Diseases

- Genetic Syndromes associated with Congenital Heart Disease

- Prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease and Metabolic Syndrome in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease

- 2 Cases of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome