Investig Clin Urol.

2018 Sep;59(5):335-341. 10.4111/icu.2018.59.5.335.

Clinical characteristics of postoperative febrile urinary tract infections after ureteroscopic lithotripsy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea. urokbs@knu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Urology, Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, Daegu, Korea.

- 3Department of Urology, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea.

- KMID: 2419417

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2018.59.5.335

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Ureteroscopic lithotripsy (URS) is gaining popularity for the management of ureteral stones and even renal stones, with high efficacy and minimal invasiveness. Although this procedure is known to be safe and to have a low complication rate, febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) after URS is not rare. Therefore, we aimed to analyze the risk factors and causative pathogens of febrile UTI after URS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 2013 and June 2015, 304 patients underwent URS for ureteral or renal stones. The rate of postoperative febrile UTI and the causative pathogens were verified, and the risk factors for postoperative febrile UTI were analyzed using logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

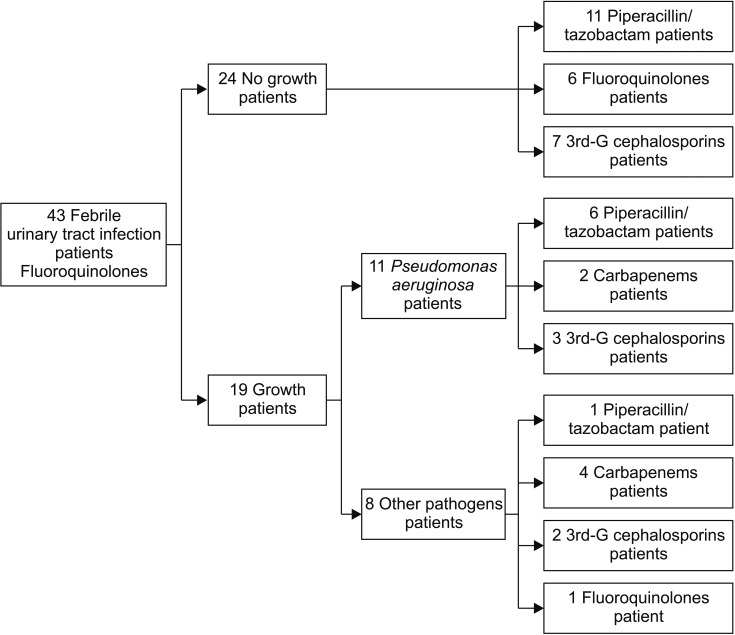

Of 304 patients, postoperative febrile UTI occurred in 43 patients (14.1%). Of them, pathogens were cultured in blood or urine in 19 patients (44.2%), and definite pathogens were not identified in 24 patients (55.8%). In patients with an identified pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa had the highest incidence. Multivariate analysis showed that the operation time (p < 0.001) was an independent risk factor for febrile UTI after URS. The cut-off value of operation time for increased risk of febrile UTI was 70 minutes.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, febrile UTI after URS occurred in 14.1% of patients, and the operation time was an independent predictive factor for this complication. Considering that more than 83.7% of febrile UTIs after URS were not controlled with fluoroquinolones, it may be more appropriate to use higher-level antibiotics for treatment, even in cases with unidentified pathogens.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

2. Takagi T, Go T, Takayasu H, Aso Y. Fiberoptic pyeloureteroscope. Surgery. 1971; 70:661–663. PMID: 5120887.3. Bush IM, Goldberg E, Javadpour N, Chakrobortty H, Morelli F. Ureteroscopy and renoscopy: a preliminary report. Chic Med Sch Q. 1970; 30:46–49. PMID: 5317579.4. Aboumarzouk OM, Monga M, Kata SG, Traxer O, Somani BK. Flexible ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy for stones >2 cm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol. 2012; 26:1257–1263. PMID: 22642568.5. Stav K, Cooper A, Zisman A, Leibovici D, Lindner A, Siegel YI. Retrograde intrarenal lithotripsy outcome after failure of shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol. 2003; 170:2198–2201. PMID: 14634378.

Article6. Fabrizio MD, Behari A, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic management of intrarenal calculi. J Urol. 1998; 159:1139–1143. PMID: 9507817.

Article7. Volkin D, Shah O. Complications of ureteroscopy for stone disease. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2016; 68:570–585. PMID: 27441595.8. Geavlete P, Georgescu D, Niţă G, Mirciulescu V, Cauni V. Complications of 2735 retrograde semirigid ureteroscopy procedures: a single-center experience. J Endourol. 2006; 20:179–185. PMID: 16548724.

Article9. Skolarikos A, Mitsogiannis H, Deliveliotis C. Indications, prediction of success and methods to improve outcome of shock wave lithotripsy of renal and upper ureteral calculi. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2010; 82:56–63. PMID: 20593724.10. Breda A, Ogunyemi O, Leppert JT, Schulam PG. Flexible ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy for multiple unilateral intrarenal stones. Eur Urol. 2009; 55:1190–1196. PMID: 18571315.

Article11. Cindolo L, Castellan P, Scoffone CM, Cracco CM, Celia A, Paccaduscio A, et al. Mortality and flexible ureteroscopy: analysis of six cases. World J Urol. 2016; 34:305–310. PMID: 26210344.

Article12. Wolf JS, Bennett CJ, Dmochowski RR, Hollenbeck BK, Pearle MS, Schaeffer AJ. Best practice policy statement on urologic surgery antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol. 2008; 179:1379–1390. PMID: 18280509.

Article13. Knopf HJ, Graff HJ, Schulze H. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in ureteroscopic stone removal. Eur Urol. 2003; 44:115–118. PMID: 12814685.

Article14. Mitsuzuka K, Nakano O, Takahashi N, Satoh M. Identification of factors associated with postoperative febrile urinary tract infection after ureteroscopy for urinary stones. Urolithiasis. 2016; 44:257–262. PMID: 26321205.

Article15. Sohn DW, Kim SW, Hong CG, Yoon BI, Ha US, Cho YH. Risk factors of infectious complication after ureteroscopic procedures of the upper urinary tract. J Infect Chemother. 2013; 19:1102–1108. PMID: 23783396.

Article16. Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34:1–14. PMID: 23221186.

Article17. Kang CI, Kim J, Park DW, Kim BN, Ha US, Lee SJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the antibiotic treatment of community-acquired urinary tract infections. Infect Chemother. 2018; 50:67–100. PMID: 29637759.

Article18. Kim ME, Ha US, Cho YH. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens causing acute uncomplicated cystitis in female outpatients in South Korea: a multicentre study in 2006. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008; 31(Suppl 1):S15–S18. PMID: 18096373.

Article19. Polk RE, Johnson CK, McClish D, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Predicting hospital rates of fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa from fluoroquinolone use in US hospitals and their surrounding communities. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:497–503. PMID: 15356812.

Article20. Grabe M, Botto H, Cek M, Tenke P, Wagenlehner FM, Naber KG, et al. Preoperative assessment of the patient and risk factors for infectious complications and tentative classification of surgical field contamination of urological procedures. World J Urol. 2012; 30:39–50. PMID: 21779836.

Article21. Tuzel E, Aktepe OC, Akdogan B. Prospective comparative study of two protocols of antibiotic prophylaxis in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2013; 27:172–176. PMID: 22908891.

Article22. Singla M, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Gupta N, Ansari MS, Dubey D, et al. Aggressive approach to staghorn calculi-safety and efficacy of multiple tracts percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urology. 2008; 71:1039–1042. PMID: 18279934.

Article23. Osther PJS. Risks of flexible ureterorenoscopy: pathophysiology and prevention. Urolithiasis. 2018; 46:59–67. PMID: 29151117.

Article24. Lildal SK, Andreassen KH, Christiansen FE, Jung H, Pedersen MR, Osther PJ. Pharmacological relaxation of the ureter when using ureteral access sheaths during ureterorenoscopy: a randomized feasibility study in a porcine model. Adv Urol. 2016; 10. 20. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1155/2016/8064648.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Unexpected Septic Shock after Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy in a Patient Preoperatively Treated for a Urinary Tract Infection

- Feasibility of Anesthesia-Free Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy in Elderly Patients with Urinary Tract Infections

- Comparison of Shock Wave Lithotripsy and Ureteroscopic Laser Lithotripsy in the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Stones

- Is Preoperative Pyuria Associated with Postoperative Febrile Complication after Ureteroscopic Ureter or Renal Stone Removal?

- Significance of albumin to globulin ratio as a predictor of febrile urinary tract infection after ureteroscopic lithotripsy