J Bone Metab.

2016 Aug;23(3):149-155. 10.11005/jbm.2016.23.3.149.

Prolonged Practice of Swimming Is Negatively Related to Bone Mineral Density Gains in Adolescents

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physical Education, Laboratory of InVestigation in Exercise (LIVE), São Paulo State University (UNESP), Presidente Prudente, Brazil. ricardoagostinete@gmail.com

- 2Post-Graduation Program in Kinesiology, Institute of Biosciences, São Paulo State University (UNESP), Rio Claro, Brazil.

- 3Department of Physical Therapy, Post-Graduation Program in Physical Therapy, São Paulo State University (UNESP), Presidente Prudente, Brazil.

- KMID: 2350811

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2016.23.3.149

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The practice of swimming in "hypogravity" conditions has potential to decrease bone formation because it decreases the time engaged in weight-bearing activities usually observed in the daily activities of adolescents. Therefore, adolescents competing in national levels would be more exposed to these deleterious effects, because they are engaged in long routines of training during most part of the year. To analyze the effect of swimming on bone mineral density (BMD) gain among adolescents engaged in national level competitions during a 9-month period.

METHODS

Fifty-five adolescents; the control group contained 29 adolescents and the swimming group was composed of 26 athletes. During the cohort study, BMD, body fat (BF) and fat free mass (FFM) were assessed using a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanner. Body weight was measured with an electronic scale, and height was assessed using a stadiometer.

RESULTS

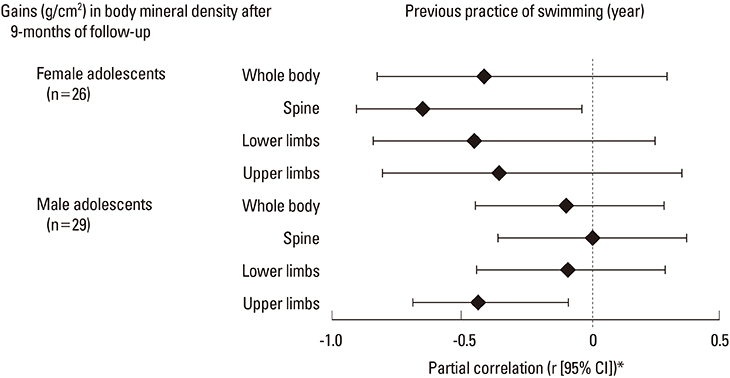

During the follow-up, swimmers presented higher gains in FFM (Control 2.35 kg vs. Swimming 5.14 kg; large effect size [eta-squared (ES-r)=0.168]) and BMD-Spine (Swimming 0.087 g/cm² vs. Control 0.049 g/cm²; large effect size [ES-r=0.167]) compared to control group. Male swimmers gained more FFM (Male 10.63% vs. Female 3.39%) and BMD-Spine (Male 8.47% vs. Female 4.32%) than females. Longer participation in swimming negatively affected gains in upper limbs among males (r=-0.438 [-0.693 to -0.085]), and in spine among females (r=-0.651 [-0.908 to -0.036]).

CONCLUSIONS

Over a 9-month follow-up, BMD and FFM gains were more evident in male swimmers, while longer engagement in swimming negatively affected BMD gains, independently of sex.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Track and Field Practice and Bone Outcomes among Adolescents: A Pilot Study (ABCD-Growth Study)

Yuri da Silva Ventura Faustino-da-Silva, Ricardo Ribeiro Agostinete, André Oliveira Werneck, Santiago Maillane-Vanegas, Kyle Robinson Lynch, Isabella Neto Exupério, Igor Hideki Ito, Romulo Araújo Fernandes

J Bone Metab. 2018;25(1):35-42. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2018.25.1.35.

Reference

-

1. Winsloe C, Earl S, Dennison EM, et al. Early life factors in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009; 7:140–144.

Article2. Rachner TD, Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis: now and the future. Lancet. 2011; 377:1276–1287.

Article3. Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Christiansen C, et al. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994; 9:1137–1141.

Article4. Gunter KB, Almstedt HC, Janz KF. Physical activity in childhood may be the key to optimizing lifespan skeletal health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012; 40:13–21.

Article5. Bailey DA, Faulkner RA, McKay HA. Growth, physical activity, and bone mineral acquisition. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1996; 24:233–266.

Article6. Milgrom C, Simkin A, Eldad A, et al. Using bone's adaptation ability to lower the incidence of stress fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2000; 28:245–251.

Article7. Nordström A, Karlsson C, Nyquist F, et al. Bone loss and fracture risk after reduced physical activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2005; 20:202–207.

Article8. Saggese G, Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S. Osteoporosis in children and adolescents: diagnosis, risk factors, and prevention. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001; 14:833–859.

Article9. Gómez-Cabello A, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Albers U, et al. Harmonization process and reliability assessment of anthropometric measurements in the elderly EXERNET multi-centre study. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e41752.

Article10. Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. 2005; 146:732–737.

Article11. Frost HM, Schönau E. The "muscle-bone unit" in children and adolescents: a 2000 overview. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000; 13:571–590.

Article12. Vicente-Rodríguez G. How does exercise affect bone development during growth? Sports Med. 2006; 36:561–569.

Article13. Karlsson MK, Nordqvist A, Karlsson C. Physical activity increases bone mass during growth. Food Nutr Res. 2008; 52.

Article14. Guadalupe-Grau A, Fuentes T, Guerra B, et al. Exercise and bone mass in adults. Sports Med. 2009; 39:439–468.

Article15. Kostka T, Furgal W, Gawronski W, et al. Recommendations of the Polish Society of Sports Medicine on age criteria while qualifying children and youth for participation in various sports. Br J Sports Med. 2012; 46:159–162.

Article16. Gómez-Bruton A, Gónzalez-Agüero A, Gómez-Cabello A, et al. Is bone tissue really affected by swimming? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e70119.

Article17. Gómez-Bruton A, González-Agüero A, Gómez-Cabello A, et al. Swimming and bone: is low bone mass due to hypogravity alone or does other physical activity influence it? Osteoporos Int. 2016; 27:1785–1793.

Article18. Gómez-Bruton A, González-Agüero A, Gómez-Cabello A, et al. The effects of swimming training on bone tissue in adolescence. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015; 25:e589–e602.

Article19. Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Bailey DA, et al. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002; 34:689–694.

Article20. Bellew JW, Gehrig L. A comparison of bone mineral density in adolescent female swimmers, soccer players, and weight lifters. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006; 18:19–22.

Article21. Sanchis-Moysi J, Dorado C, Olmedillas H, et al. Bone mass in prepubertal tennis players. Int J Sports Med. 2010; 31:416–420.

Article22. Vicente-Rodriguez G, Dorado C, Perez-Gomez J, et al. Enhanced bone mass and physical fitness in young female handball players. Bone. 2004; 35:1208–1215.

Article23. Davies JH, Evans BA, Gregory JW. Bone mass acquisition in healthy children. Arch Dis Child. 2005; 90:373–378.

Article24. Loomba-Albrecht LA, Styne DM. Effect of puberty on body composition. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009; 16:10–15.

Article25. Andreoli A, Monteleone M, Van Loan M, et al. Effects of different sports on bone density and muscle mass in highly trained athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001; 33:507–511.

Article26. Taaffe DR, Snow-Harter C, Connolly DA, et al. Differential effects of swimming versus weight-bearing activity on bone mineral status of eumenorrheic athletes. J Bone Miner Res. 1995; 10:586–593.

Article27. Taaffe DR, Marcus R. Regional and total body bone mineral density in elite collegiate male swimmers. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1999; 39:154–159.28. Ferry B, Lespessailles E, Rochcongar P, et al. Bone health during late adolescence: effects of an 8-month training program on bone geometry in female athletes. Joint Bone Spine. 2013; 80:57–63.

Article29. Czeczelewski J, Długołęcka B, Czeczelewska E, et al. Intakes of selected nutrients, bone mineralisation and density of adolescent female swimmers over a three-year period. Biol Sport. 2013; 30:17–20.

Article30. Taaffe DR, Robinson TL, Snow CM, et al. High-impact exercise promotes bone gain in well-trained female athletes. J Bone Miner Res. 1997; 12:255–260.

Article31. Fehling PC, Alekel L, Clasey J, et al. A comparison of bone mineral densities among female athletes in impact loading and active loading sports. Bone. 1995; 17:205–210.

Article32. Risser WL, Lee EJ, LeBlanc A, et al. Bone density in eumenorrheic female college athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990; 22:570–574.

Article33. Nemet D, Oh Y, Kim HS, et al. Effect of intense exercise on inflammatory cytokines and growth mediators in adolescent boys. Pediatrics. 2002; 110:681–689.

Article34. Andreoli A, Celi M, Volpe SL, et al. Long-term effect of exercise on bone mineral density and body composition in post-menopausal ex-elite athletes: a retrospective study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012; 66:69–74.

Article35. Hind K, Truscott JG, Evans JA. Low lumbar spine bone mineral density in both male and female endurance runners. Bone. 2006; 39:880–885.

Article36. Ackerman KE, Misra M. Bone health and the female athlete triad in adolescent athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 2011; 39:131–141.

Article37. Ackerman KE, Skrinar GS, Medvedova E, et al. Estradiol levels predict bone mineral density in male collegiate athletes: a pilot study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012; 76:339–345.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Swimming-induced Influences on Bone Density in Middle-aged Women

- The relationship of maturation value of vaginal epithelium and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women

- Measurement of bone mineral density in Korean newborns by dual photon absorptiometry

- Effects of Different Types of Mechanical Loading on Trabecular Bone Microarchitecture in Rats

- Diagnostic Value of the Bone Mineral Densitometry in the Metastatic Prostatic Cancer