J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2013 Dec;54(12):1929-1934.

Efficacy of Autologous Tragal Perichondrium Graft after Proper Antifungal Treatment in Fungal Necrotizing Scleritis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. Jck50ey@kornet.net

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To compare the efficacy of an autologous tragal perichondrium graft after proper antifungal treatment between 2 cases of fungal necrotizing scleritis.

CASE SUMMARY

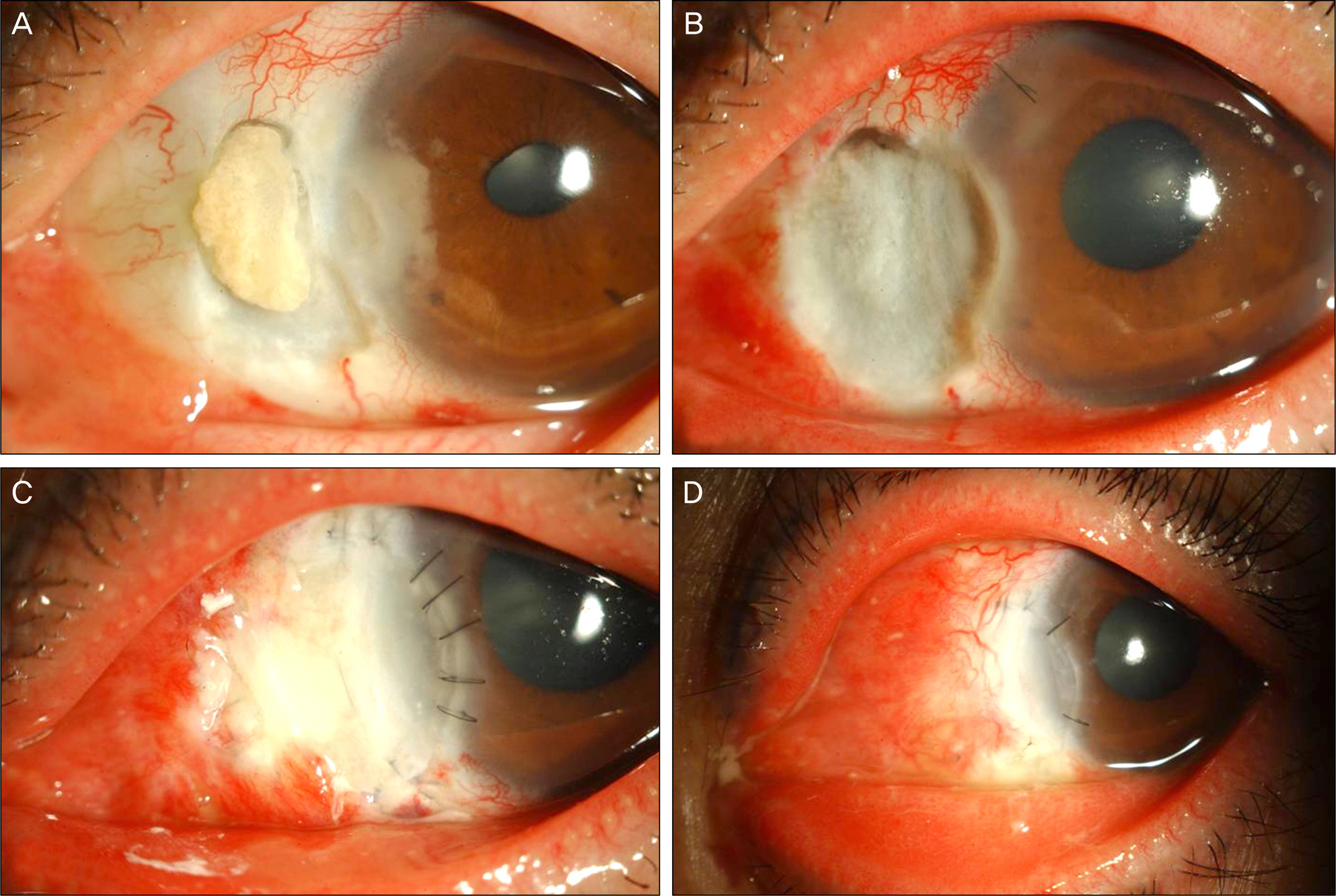

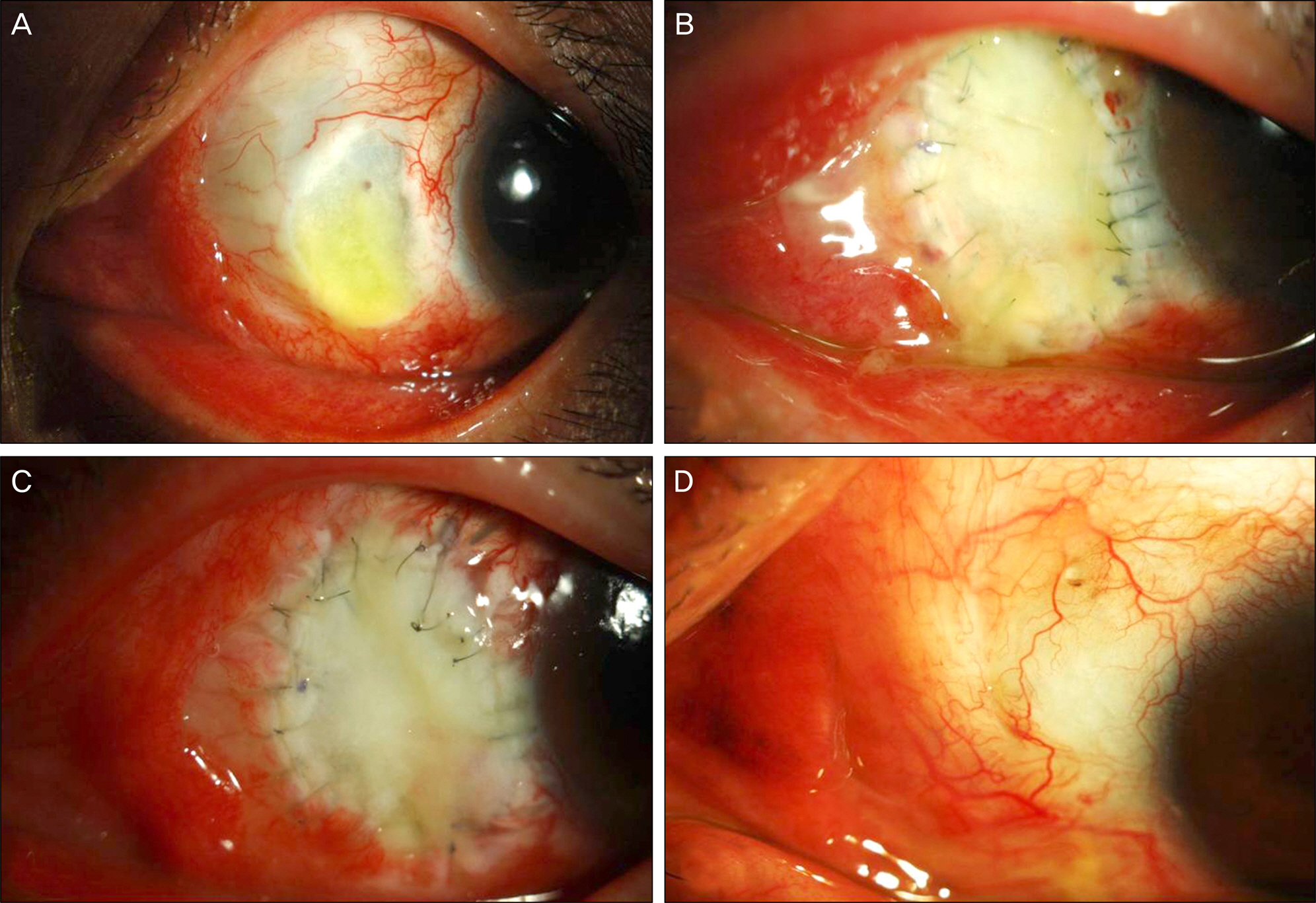

A 58-year-old female was referred to our clinic with fungal necrotizing scleritis of the left eye which had occurred after pterygium removal. Scleral melting around calcification was observed. After proper treatment with antifungal agents, the authors performed autologous tragal perichondrium graft; however, 3 months after surgery, a necrosis of sclera recurred and the, patient underwent additional treatment with antifungal agents. No complication has been observed up to 3 months postoperatively. A 36-year-old male visited our clinic with ocular pain and decreased visual acuity associated with necrotizing scleritis which occurred after local conjunctival resection. After 4 weeks of antifungal treatments, scleral lesions were stabilized and the authors confirmed negative findings with repetitive fungus smear test. Therapeutic autologous tragal perichondrium graft was performed, and no complication was observed 3 months postoperatively.

CONCLUSIONS

When treating a patient with fungal necrotizing scleritis, preoperative antifungal therapy and confirmation of negative findings in repetitive fungus smear test are important. Autologus tragal perichondrium graft accompanied with proper antifungal therapy is an effective treatment of fungal necrotizing scleritis.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Lee DC, Lee JW, Chang SD. A case of fusarium keratitis treated with Moxifloxacin 0.5% ophthalmic solution. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2012; 53:338–41.

Article2. O’ Day DM. Selection of appropriate antifungal therapy. Cornea. 1987; 6:238–45.

Article3. Kim YS, Song YS, Kim JC. Fungal keratitis caused by chromomycetes. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2003; 44:755–9.4. Cavaliere M, Mottola G, Rondinelli M, Iemma M. Tragal cartilage in tympanoplasty: anatomic and functional results in 306 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009; 29:27–32.5. Yoon CH, Kim NJ, Lee MJ. . Correction of lower lid retraction using autologous ear cartilage graft. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2011; 52:136–40.

Article6. Nigro MV, Friedhofer H, Natalino RJ, Ferreira MC. Comparative analysis of the influence of perichondrium on conjunctival epithelialization on conchal cartilage grafts in eyelid reconstruction: experimental study in rabbits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123:55–63.

Article7. Moriarty AP, Crawford GJ, McAllister IL, Constable IJ. Severe corneoscleral infection : a complication of beta irradiation scleral necrosis following pterygium excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993; 111:947–51.8. Moriarty AP, Crawford GJ, McAllister IL, Constable IJ. Bilateral streptococcal corneoscleritis complicating beta irradiation induced scleral necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993; 77:251–2.

Article9. Hayasaka S, Noda S, Yamamoto Y, Setogawa T. Postoperative in-stillation of mitomycin C in the treatment of recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989; 20:580–3.

Article10. Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM. . Serious complications of topical mitomycin-C after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992; 99:1647–54.

Article11. Wong TY, Ng TP, Fong KS, Tan DT. Risk factors and clinical out-comes between fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparative study. CLAO J. 1997; 23:275–81.12. Lee KH, Chae HJ, Yoon KC. Analysis of risk factors for treatment failure in fungal keratitis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008; 49:737–42.

Article13. Madsen K, Mark K, van Menxel M, Friberg U. Analysis of collagen types synthesized by rabbit ear cartilage chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Biochem J. 1984; 221:189–96.

Article14. Togo T, Utani A, Naitoh M. . Identification of cartilage progen-itor cells in the adult ear perichondrium: utilization for cartilage reconstruction. Lab Invest. 2006; 86:445–57.

Article15. Koo H, Jeong JH, Chun YS, Kim JC. Ocular reconstruction using autologous tragal perichondrium for a refractory necrotizing scler-al perforation: a case report. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2011; 52:1227–31.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ocular Reconstruction Using Autologous Tragal Perichondrium for a Refractory Necrotizing Scleral Perforation: A Case Report

- A Case of Autologous Tragal Perichondrium Graft in a Patient with Mooren's Ulcer

- Autologous Tragal Perichondrium Transplantation: A Novel Approach for the Management of Painful Bullous Keratopathy

- Successful Treatment of Infectious Scleritis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Autologous Perichondrium Graft of Conchal Cartilage

- Simultaneous Four-site Restoration of Bilateral Scleromalacia Using Autologous Tragal Perichondrium and Preserved Sclera