J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2012 Jun;53(6):895-900.

Two Cases of Ocular Complications Caused by Phendimetrazine

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea. parkjm@gnu.ac.kr

- 2Gyeongsang Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Korea.

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The authors of the present study report treatment experience of acute myopia and branch retinal vein occlusion associated with phendimetrazine, a drug used for weight reduction.

CASE SUMMARY

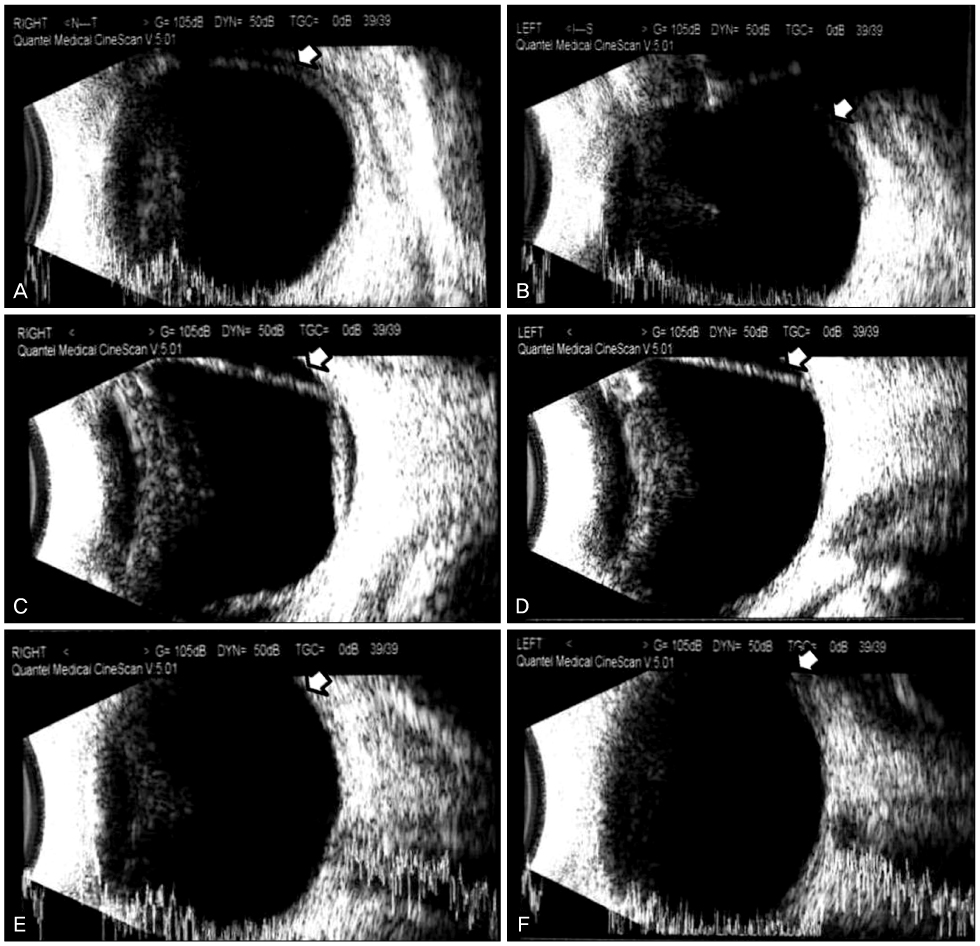

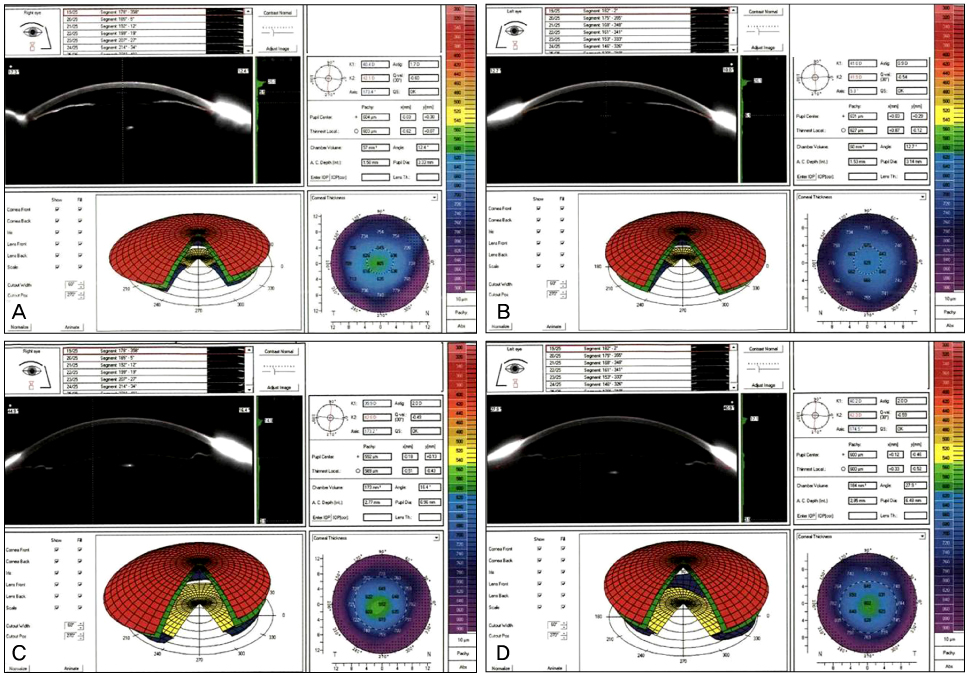

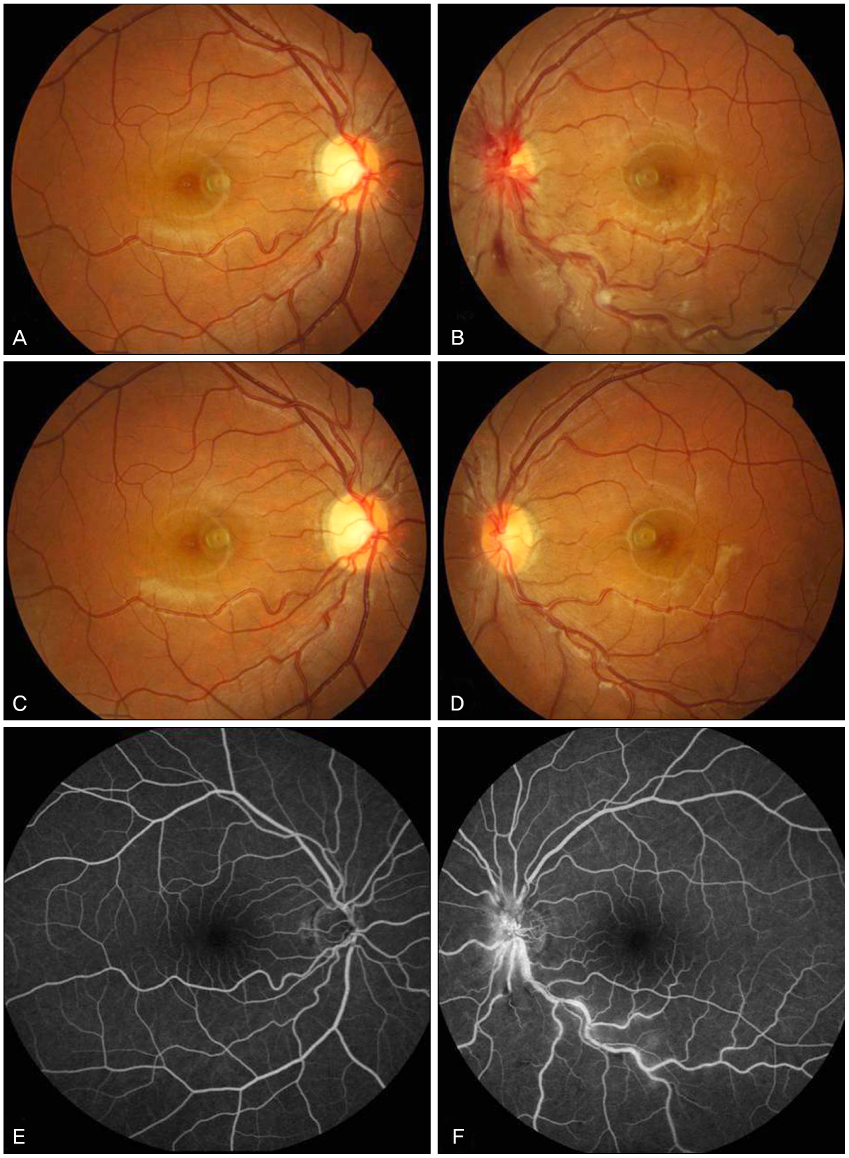

Case 1: A 32-year-old woman, previously devoid of ocular problems, visited our hospital with bilateral visual disturbance after taking phendimetrazine for weight reduction. Ciliochoroidal effusion and anterior shifting of the lens-iris diaphragm were observed, which resulted in a shallow anterior chamber, myopic shifting and an increase in intraocular pressure due to angle closure. The symptoms were relieved by discontinuing the use of phendimetrazine and administration of intraocular pressure-lowering agents. Case 2: A 26-year-old woman, previously devoid of ocular problems, visited our hospital with left superior visual field disturbance after taking phendimetrazine for weight reduction. The examinations revealed papilledema, disc hemorrhage and tortuous vascular changes in her left eye. Fluorescein angiography was performed, and retinal vein occlusion was diagnosed. The patient discontinued weight reduction agents and recovered while under observation.

CONCLUSIONS

Phendimetrazine, used for weight reduction, can cause acute myopia via prostaglandin synthesis and retinal venous occlusion due to vascular constriction.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bray GA. Concise review on the therapeutics of obesity. Nutrition. 2000. 16:953–960.2. Grinbaum A, Ashkenazi I, Gutman I, Blumenthal M. Suggested mechanism for acute transient myopia after sulfonamide treatment. Ann Ophthalmol. 1993. 25:224–226.3. Chirls IA, Norris JW. Transient myopia associated with vaginal sulfanilamide suppositories. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984. 98:120–121.4. Geanon JD, Perkins TW. Bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma associated with drug sensitivity to hydrochlorothiazide. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995. 113:1231–1232.5. Rhee DJ, Goldberg MJ, Parrish RK. Bilateral angle-closure glaucoma and ciliary body swelling from topiramate. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001. 119:1721–1723.6. Medeiros FA, Zhang XY, Bernd AS, Weinreb RN. Angle-closure glaucoma associated with ciliary body detachment in patients using topiramate. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003. 121:282–285.7. Fan JT, Johnson DH, Burk RR. Transient myopia, angle-closure glaucoma, and choroidal detachment after oral acetazolamide. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993. 115:813–814.8. Postel EA, Assalian A, Epstein DL. Drug-induced transient myopia and angle-closure glaucoma associated with supraciliary choroidal effusion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996. 122:110–112.9. Krieg PH, Schipper I. Drug-induced ciliary body oedema: a new theory. Eye (Lond). 1996. 10:121–126.10. Söylev MF, Green RL, Feldon SE. Choroidal effusion as a mechanism for transient myopia induced by hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995. 120:395–397.11. Lee W, Chang JH, Roh KH, et al. Anorexiant-induced transient myopia after myopic laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007. 33:746–749.12. Bhattacherjee P, Mukhopadhyay P, Tilley SL, et al. Blood-aqueous barrier in prostaglandin EP2 receptor knockout mice. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2002. 10:187–196.13. Biswas S, Bhattacherjee P, Paterson CA. Prostaglandin E2 receptor subtypes, EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 in human and mouse ocular tissues--a comparative immunohistochemical study. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004. 71:277–288.14. Bovino JA, Marcus DF. The mechanism of transient myopia induced by sulfonamide therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982. 94:99–102.15. Krieg PH, Schipper I. Drug-induced ciliary body oedema: a new theory. Eye (Lond). 1996. 10:121–126.16. Hook SR, Holladay JT, Prager TC, Goosey JD. Transient myopia induced by sulfonamides. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986. 101:495–496.17. Kim SW, Seo SG, Her J, et al. Two cases of topiramate-induced acute myopia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008. 49:1033–1040.18. Jeon C, Kee CW. Topiramate-induced acute angle-closure glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005. 46:1944–1950.19. Moon SH, Hwang BS, Chang WH. Clinical course of young adults with central retinal vein occlusion. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008. 49:1948–1953.20. Goodman Gilman A, Rall TW, Nies AS, Talyor P. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 1990. 8th ed. New York: Pergamon Press;210–214.21. Comay D, Ramsay J, Irvine EJ. Ischemic colitis after weight-loss medication. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003. 17:719–721.22. Kokkinos J, Levine SR. Possible association of ischemic stroke with phentermine. Stroke. 1993. 24:310–313.23. Landau D, Jackson J, Gonzalez G. A case of demand ischemia from phendimetrazine. Cases J. 2008. 1:105.24. Rostagno C, Caciolli S, Felici M, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy associated with chronic consumption of phendimetrazine. Am Heart J. 1996. 131:407–409.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Phendimetrazine Induced-Psychotic Disorder and Dependence

- Two Cases of Psychotic Disorder Following Phendimetrazine Use

- A Case of Ischemic Stroke Associated with Phendimetrazine as an Appetite Suppressant

- Phentermine and Phendimetrazine-Induced Psychotic Disorder and Bipolar Disorder: A Case Series

- Psychotic Disorder Induced by Appetite Suppressants, Phentermine or Phendimetrazine: A Case Series Study