Clin Nutr Res.

2014 Jan;3(1):9-16. 10.7762/cnr.2014.3.1.9.

Basophil Activation Test with Food Additives in Chronic Urticaria Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine 110-744, Seoul, Korea. addchang@snu.ac.kr

- 2Institute of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Seoul National University Medical Research Center 110-744, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam 463-707, Korea.

- KMID: 2279616

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2014.3.1.9

Abstract

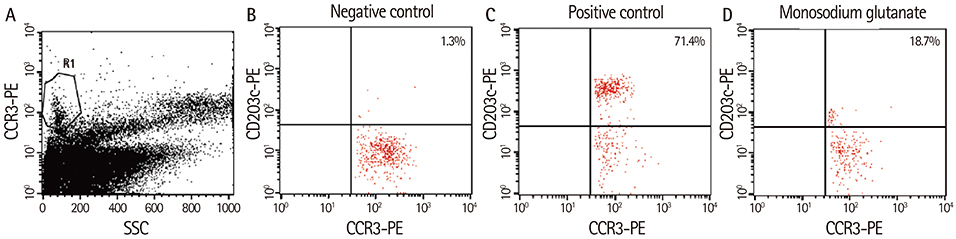

- The role of food additives in chronic urticaria (CU) is still under investigation. In this study, we aimed to explore the association between food additives and CU by using the basophil activation test (BAT). The BAT using 15 common food additives was performed for 15 patients with CU who had a history of recurrent urticarial aggravation following intake of various foods without a definite food-specific IgE. Of the 15 patients studied, two (13.3%) showed positive BAT results for one of the tested food additives. One patient responded to monosodium glutamate, showing 18.7% of CD203c-positive basophils. Another patient showed a positive BAT result to sodium benzoate. Both patients had clinical correlations with the agents, which were partly determined by elimination diets. The present study suggested that at least a small proportion of patients with CU had symptoms associated with food additives. The results may suggest the potential utility of the BAT to identity the role of food additives in CU.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau A, Grattan CE, Kapp A, Merk HF, Rogala B, Saini S, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Schünemann H, Staubach P, Vena GA, Wedi B, Maurer M. Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Global Allergy and Asthma European Network. European Dermatology Forum. World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009; 64:1417–1426.

Article2. Juhlin L. Recurrent urticaria: clinical investigation of 330 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1981; 104:369–381.

Article3. Maurer M, Ortonne JP, Zuberbier T. Chronic urticaria: an internet survey of health behaviours, symptom patterns and treatment needs in European adult patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 160:633–641.

Article4. Kobza Black A, Greaves MW, Champion RH, Pye RJ. The urticarias. Br J Dermatol. 1991; 124:100–108.5. Simon RA. Adverse reactions to food additives. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003; 3:62–66.

Article6. Food and Drug Administration (US). Everything added to food in the United States (EAFUS) [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): Food and Drug Administration;2011. cited 2011 November 8. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fcn/fcnNavigation.cfm?rpt=eafusListing.7. Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Bend J, Bolger M, Knaap AG, Kuznesof PM, Larsen JC, Mattia A, Meylan I, Pitt JI, Resnik S, Schlatter J, Vavasour E, Rao MV, Verger P, Walker R, Wallin H, Whitehouse B, Abbott PJ, Adegoke G, Baan R, Baines J, Barlow S, Benford D, Bruno A, Charrondiere R, Chen J, Choi M, DiNovi M, Fisher CE, Iseki N, Kawamura Y, Konishi Y, Lawrie S, Leblanc JC, Leclercq C, Lee HM, Moy G, Munro IC, Nishikawa A, Olempska-Beer Z, de Peuter G, Pronk ME, Renwick AG, Sheffer M, Sipes IG, Tritscher A, Soares LV, Wennberg A, Williams GM. Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2007; 1–225.8. Asero R. Multiple intolerance to food additives. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 110:531–532.

Article9. Genton C, Frei PC, Pécoud A. Value of oral provocation tests to aspirin and food additives in the routine investigation of asthma and chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985; 76:40–45.

Article10. Di Lorenzo G, Pacor ML, Mansueto P, Martinelli N, Esposito-Pellitteri M, Lo Bianco C, Ditta V, Leto-Barone MS, Napoli N, Di Fede G, Rini G, Corrocher R. Food-additive-induced urticaria: a survey of 838 patients with recurrent chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005; 138:235–242.

Article11. Devlin J, David TJ. Tartrazine in atopic eczema. Arch Dis Child. 1992; 67:709–711.

Article12. Pestana S, Moreira M, Olej B. Safety of ingestion of yellow tartrazine by double-blind placebo controlled challenge in 26 atopic adults. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2010; 38:142–146.

Article13. Park HW, Park CH, Park SH, Park JY, Park HS, Yang HJ, Ahn KM, Kim KH, Oh JW, Kim KE, Pyun BY, Lee HB, Min KU. Dermatologic adverse reactions to 7 common food additives in patients with allergic diseases: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:1059–1061.

Article14. Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 2: diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 103:981–989.

Article15. Bock SA, Sampson HA, Atkins FM, Zeiger RS, Lehrer S, Sachs M, Bush RK, Metcalfe DD. Double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) as an office procedure: a manual. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988; 82:986–997.

Article16. Zuberbier T, Chantraine-Hess S, Hartmann K, Czarnetzki BM. Pseudoallergen-free diet in the treatment of chronic urticaria. A prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995; 75:484–487.17. Supramaniam G, Warner JO. Artificial food additive intolerance in patients with angio-oedema and urticaria. Lancet. 1986; 2:907–909.

Article18. Hamilton RG, Franklin Adkinson N Jr. In vitro assays for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:213–225.

Article19. Erdmann SM, Heussen N, Moll-Slodowy S, Merk HF, Sachs B. CD63 expression on basophils as a tool for the diagnosis of pollen-associated food allergy: sensitivity and specificity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003; 33:607–614.

Article20. Ebo DG, Hagendorens MM, Bridts CH, Schuerwegh AJ, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ. Flow cytometric analysis of in vitro activated basophils, specific IgE and skin tests in the diagnosis of pollen-associated food allergy. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2005; 64:28–33.

Article21. Pinnobphun P, Buranapraditkun S, Kampitak T, Hirankarn N, Klaewsongkram J. The diagnostic value of basophil activation test in patients with an immediate hypersensitivity reaction to radiocontrast media. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 106:387–393.

Article22. Abuaf N, Rajoely B, Ghazouani E, Levy DA, Pecquet C, Chabane H, Leynadier F. Validation of a flow cytometric assay detecting in vitro basophil activation for the diagnosis of muscle relaxant allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 104:411–418.

Article23. Sanz ML, Gamboa PM, Antépara I, Uasuf C, Vila L, Garcia-Avilés C, Chazot M, De Weck AL. Flow cytometric basophil activation test by detection of CD63 expression in patients with immediate-type reactions to betalactam antibiotics. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002; 32:277–286.

Article24. Gamboa P, Sanz ML, Caballero MR, Urrutia I, Antépara I, Esparza R, de Weck AL. The flow-cytometric determination of basophil activation induced by aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is useful for in vitro diagnosis of the NSAID hypersensitivity syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004; 34:1448–1457.

Article25. Kim JH, An S, Kim JE, Choi GS, Ye YM, Park HS. Beef-induced anaphylaxis confirmed by the basophil activation test. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010; 2:206–208.

Article26. Song WJ, Chang YS. Recent applications of basophil activation tests in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013; 3:266–280.

Article27. Min KU. Skin test, RAST and provocation test in food allergy. Allergy. 1991; 11:576–583.28. BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG. BÜHLMANN allergen list [Internet]. Schönenbuch: BÜHLMANN Laboratories AG;2013. cited 2005 July 25. Available from: http://http://www.buhlmannlabs.ch/files/documents/core/CellularAllergy/Corporate/allergenliste-ml15e.pdf.29. Sabroe RA, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria with functional autoantibodies: 12 years on. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 154:813–819.30. Chang YS. Urticaria and anaphylaxis. Korean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 26:S152–S160.31. Kang KS, Han HJ, Lee JO, Park CW, Lee CH. A study of food allergy in patients with urticaria. Korean J Dermatol. 2004; 42:1106–1113.32. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:S116–S125.

Article33. Wilson BG, Bahna SL. Adverse reactions to food additives. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005; 95:499–507.

Article34. Simon RA. Adverse reactions to food and drug additives. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 1996; 16:137–176.

Article35. Jansen JJ, Kardinaal AF, Huijbers G, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Martens BP, Ockhuizen T. Prevalence of food allergy and intolerance in the adult Dutch population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994; 93:446–456.

Article36. Hertz B, Fuglsang G, Holm EB. Exercise-induced asthma in children and oral terbutaline. A dose-response relationship study. Ugeskr Laeger. 1994; 156:5693–5695.37. Zuberbier T, Edenharter G, Worm M, Ehlers I, Reimann S, Hantke T, Roehr CC, Bergmann KE, Niggemann B. Prevalence of adverse reactions to food in Germany - a population study. Allergy. 2004; 59:338–345.

Article38. Haustein UF. Pseudoallergen-free diet in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996; 76:498–499.39. Mlynek A, Zalewska-Janowska A, Martus P, Staubach P, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008; 63:777–780.

Article40. Magerl M, Pisarevskaja D, Scheufele R, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. Effects of a pseudoallergen-free diet on chronic spontaneous urticaria: a prospective trial. Allergy. 2010; 65:78–83.

Article41. Wedi B, Novacovic V, Koerner M, Kapp A. Chronic urticaria serum induces histamine release, leukotriene production, and basophil CD63 surface expression--inhibitory effects ofanti-inflammatory drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000; 105:552–560.

Article42. Yasnowsky KM, Dreskin SC, Efaw B, Schoen D, Vedanthan PK, Alam R, Harbeck RJ. Chronic urticaria sera increase basophil CD203c expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 117:1430–1434.

Article43. Frezzolini A, Provini A, Teofoli P, Pomponi D, De Pità O. Serum-induced basophil CD63 expression by means of a tricolour flow cytometric method for the in vitro diagnosis of chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2006; 61:1071–1077.

Article44. Najib U, Bajwa ZH, Ostro MG, Sheikh J. A retrospective review of clinical presentation, thyroid autoimmunity, laboratory characteristics, and therapies used in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009; 103:496–501.

Article45. Wanich N, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Shreffler WG. Allergen-specific basophil suppression associated with clinical tolerance in patients with milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:789–794.

Article46. Tokuda R, Nagao M, Hiraguchi Y, Hosoki K, Matsuda T, Kouno K, Morita E, Fujisawa T. Antigen-induced expression of CD203c on basophils predicts IgE-mediated wheat allergy. Allergol Int. 2009; 58:193–199.

Article47. De Week AL, Sanz ML, Gamboa PM, Aberer W, Bienvenu J, Blanca M, Demoly P, Ebo DG, Mayorga L, Monneret G, Sainte Laudy J. Diagnostic tests based on human basophils: more potentials and perspectives than pitfalls. II. Technical issues. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008; 18:143–155.48. Shreffler WG. Evaluation of basophil activation in food allergy: present and future applications. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 6:226–233.

Article49. Ocmant A, Mulier S, Hanssens L, Goldman M, Casimir G, Mascart F, Schandené L. Basophil activation tests for the diagnosis of food allergy in children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39:1234–1245.

Article50. Eberlein-König B, Schmidt-Leidescher C, Rakoski J, Behrendt H, Ring J. In vitro basophil activation using CD63 expression in patients with bee and wasp venom allergy. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006; 16:5–10.51. Rubio A, Vivinus-Nébot M, Bourrier T, Saggio B, Albertini M, Bernard A. Benefit of the basophil activation test in deciding when to reintroduce cow's milk in allergic children. Allergy. 2011; 66:92–100.

Article52. García-Ortega P, Scorza E, Teniente A. Basophil activation test in the diagnosis of sulphite-induced immediate urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010; 40:688.

Article53. Ebo DG, Ingelbrecht S, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ. Allergy for cheese: evidence for an IgE-mediated reaction from the natural dye annatto. Allergy. 2009; 64:1558–1560.

Article54. Lee SE, Lee SY, Jo EJ, Kim MY, Yang MS, Chang YS, Kim SH. A case of taurine-containing drink induced anaphylaxis. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013; 3:70–73.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Fexofenadine-Induced Urticaria

- Increased Level of Basophil CD203c Expression Predicts Severe Chronic Urticaria

- Beef-Induced Anaphylaxis Confirmed by the Basophil Activation Test

- Basophil Markers for Identification and Activation in the Indirect Basophil Activation Test by Flow Cytometry for Diagnosis of Autoimmune Urticaria

- Allergic Diseases in Childhood and Food Additives