Ann Rehabil Med.

2011 Dec;35(6):867-872. 10.5535/arm.2011.35.6.867.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders of Children Screened by The Infantile Health Promotion System

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, Goyang 410-719, Korea. snoopyhara@hanmail.net

- 2Department of Pediatrics, National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, Goyang 410-719, Korea.

- 3Department of Psychiatry, National Health Insurance Corporation Ilsan Hospital, Goyang 410-719, Korea.

- 4Department of Rehabilitation Medication, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul 135-720, Korea.

- KMID: 2266813

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2011.35.6.867

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

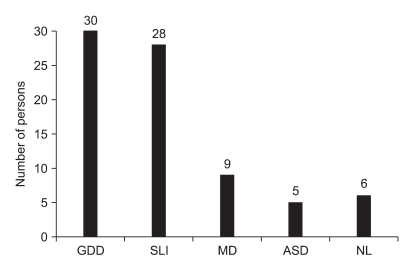

To perform an in depth evaluation of children, and thus provide a systematic method of managing children, who after infantile health screening, were categorized as suspected developmental delay. METHOD: 78 children referred to the Developmental Delay Clinic of Ilsan Hospital after suspected development delay on infantile health examinations were enrolled. A team comprised of a physiatrist, pediatrician and pediatric psychiatrist examined the patients. Neurological examination, speech and cognitive evaluation were done. Hearing tests and chromosome studies were performed when needed clinically. All referred children completed K-ASQ questionnaires. Final diagnoses were categorized into specific language impairment (SLI), global developmental delay (GDD), intellectual disability (ID), cerebral palsy (CP), motor developmental delay (MD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

RESULTS

72 of the 78 patients were abnormal in the final diagnosis, with a positive predictive value of 92.3%. Thirty (38.4%) of the 78 subjects were diagnosed as GDD, 28 (35.8%) as SLI, 5 (6.4%) as ASD, 9 (12.5%) as MD, and 6 (7.6%) as normal. Forty five of the 78 patients had risk factors related to development, and 18 had a positive family history for developmental delay and/or autistic disorders. The mean number of abnormal domains on the K-ASQ questionnaires were 3.6 for ASD, 2.7 for GDD, 1.8 for SLI and 0.6 for MD. Differences between these numbers were statistically significant (p<0.05).

CONCLUSION

Because of the high predictive value of the K-ASQ, a detailed evaluation is necessary for children suspected of developmental delay in an infantile health promotion system.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Comparison of M-B CDI-K Short Form and K-ASQ as Screening Test for Language Development

Seong Woo Kim, Ji Yong Kim, Sang Yoon Lee, Ha Ra Jeon

Ann Rehabil Med. 2016;40(6):1108-1113. doi: 10.5535/arm.2016.40.6.1108.

Reference

-

1. Cho SC. Child psychiatry perspectives on developmental disorders. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2006; 30:303–308.2. Woo YJ. Concept of developmental disability and the role of a pediatrician. Korean J Pediatr. 2006; 49:1031–1036.

Article3. Kerstjens JM, Bos AF, ten Vergert EM, de Meer G, Butcher PR, Reijneveld SA. Support for the global feasibility of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire as developmental screener. Early Hum Dev. 2009; 85:443–447. PMID: 19356866.

Article4. Santos RS, Araujo AP, Porto MA. Early diagnosis of abnormal development of preterm newborns: assessment instruments. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008; 84:289–299. PMID: 18688553.

Article5. Regalado M, Halfon N. Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years: review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001; 155:1311–1322. PMID: 11732949.6. Frankenburg WK. Developmental surveillance and screening of infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2002; 109:144–145. PMID: 11773555.

Article7. Squires J, Potter L, Bricker D. The ASQ user's guide. 1999. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Company.8. Kim EY, Sung IK. The ages and stages questionnaire: screening for developmental delay in the setting of a pediatric outpatient clinic. Korean J Pediatr. 2007; 50:1061–1066.

Article9. Eun BL, Kim SW, Kim YK, Kim JW, Moon JS, Park SK, Sung IK, Shin SM, Yoo SM, Eun SH, et al. Overview of national health screening program for infant and children. Korean J Pediatr. 2008; 51:225–232.10. Kim YT, Sung TJ, Lee YK. Preschool receptive-expressive language scale. 2003. 1st ed. Seoul: Seoul community rehabilitation center.11. Kim YT, Kim KH, Yoon HR, Kim HS. Sequenced language scale for infants. 2003. 1st ed. Seoul: Special Education Publisher.

Article12. Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant development. 1993. 2nd ed. New York: The psychological Corporation.13. Park HW, Kwak GJ, Park KB. Korean-Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence. 1998. 1st ed. Seoul: Special Education Publisher.14. Kim SW, Shin JB, Kim YH, Lee SK, Jung HJ, Song DH. Diagnosis and clinical features in children referred to developmental delay clinic. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2004; 28:132–139.15. Skellern CY, Rogers Y, O'Callaghan MJ. A parent-completed developmental questionnaire: follow up of ex-premature infants. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001; 37:125–129. PMID: 11328465.

Article16. Elbers J, Macnab A, McLeod E, Gagnon F. The ages and stages questionnaire: feasibility of use as a screening tool for children in Canada. Can J Rural Med. 2008; 13:9–14. PMID: 18208647.17. Park CI, Park ES, Shin JC, Kim SW, Choi EH. Early treatment effect in children with cerebral palsy and delayed development. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1999; 23:1127–1133.18. Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, Donaldson A, Varley J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010; 125:e17–e23. PMID: 19948568.

Article19. Squires J, Bricker D, Potter L. Revision of a parent-completed development screening tool: ages and stages questionnaires. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997; 22:313–328. PMID: 9212550.20. Klamer A, Lando A, Pinborg A, Greisen G. Ages and stages questionnaire used to measure cognitive deficit in children born extremely preterm. Acta Paediatr. 2005; 94:1327–1329. PMID: 16279000.

Article21. Richter J, Janson H. A validation study of the Norwegian version of the ages and stages questionnaires. Acta Paediatr. 2007; 96:748–752. PMID: 17462065.

Article22. Yu LM, Hey E, Doyle LW, Farrell B, Spark P, Altman DG, Duley L. Evaluation of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires in identifying children with neurosensory disability in the Magpie Trial follow-up study. Acta Paediatr. 2007; 96:1803–1808. PMID: 17971191.

Article23. Elbers J, Macnab A, McLeod E, Gagnon F. The Ages and Stages Questionnaires: feasibility of use as a screening tool for children in Canada. Can J Rural Med. 2008; 13:9–14. PMID: 18208647.24. Lindsay NM, Healy GN, Colditz PB, Lingwood BE. Use of Ages and Stages Questionnaire to predict outcome after hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy in the neonate. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008; 44:590–595. PMID: 19012632.25. Kim S, Lee JJ, Kim JH, Lee JH, Yun SW, Chae SA, Lim IS, Choi ES, Yoo BH. Changing patterns of low birth weight and associated risk factors in Korea, 1995-2007. Korean J Perinatol. 2010; 21:282–287.26. Kim MA, Kim SW, Kim YK, Chung HJ. Epilepsy, EEG abnormalities in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Korean Child Neurol Soc. 2009; 17:58–69.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of a Sociodrama-based Communication Enhancement Program on Mothers of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Pilot Study

- Prenatal Topiramate Exposure and Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Systematic Review

- The Long-Term Outcome and Rehabilitative Approach of Intraventricular Hemorrhage at Preterm Birth

- Psychological Assessment in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Socioeconomic disparities and difficulties to access to healthcare services among Canadian children with neurodevelopmental disorders and disabilities