Ann Dermatol.

2014 Dec;26(6):688-692. 10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.688.

The Effect of Environmentally Friendly Wallpaper and Flooring Material on Indoor Air Quality and Atopic Dermatitis: A Pilot Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Dermatology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea. chhuh@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2264862

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.688

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Formaldehyde (FA) and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are considered among the main causes of atopic aggravation. Their main sources include wallpapers, paints, adhesives, and flooring materials.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the effects of environmentally friendly wallpaper and flooring material on indoor air quality and atopic dermatitis severity.

METHODS

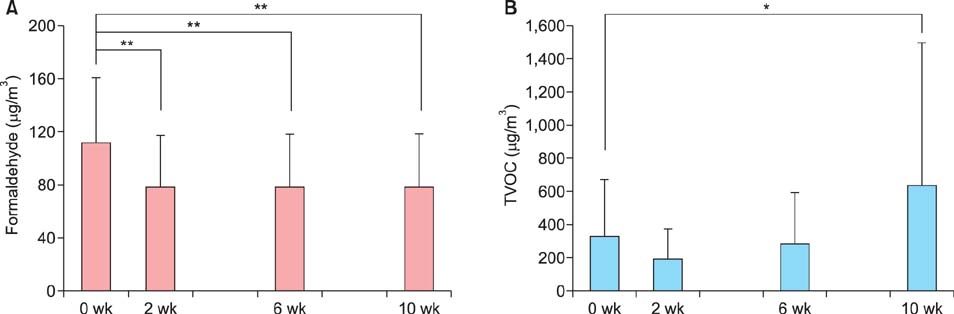

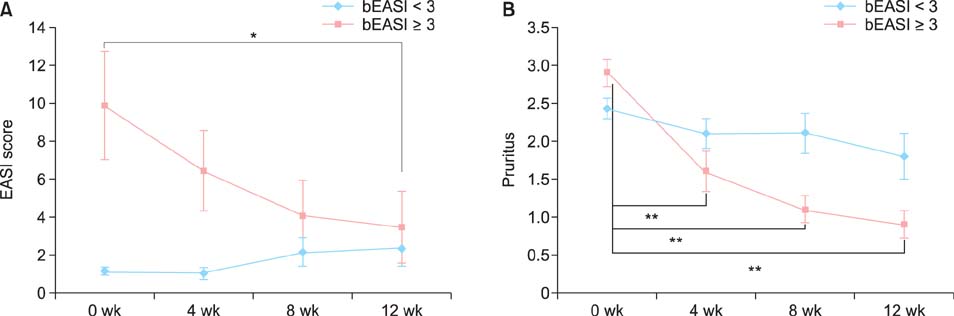

Thirty patients with atopic dermatitis were enrolled in this study. To improve air quality, the wallpaper and flooring in the homes of the subjects were replaced with plant- or silica-based materials. The indoor air concentration of FA and the total VOCs (TVOCs) were measured before remodeling and 2, 6, and 10 weeks thereafter. Pruritus and the severity of atopic eczema were evaluated by using a questionnaire and the eczema area and severity index (EASI) score before and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after remodeling. The subjects were instructed to continue their therapy for atopic dermatitis.

RESULTS

The houses of 24 subjects were remodeled; all subjects completed the study. The concentration of FA in ambient air significantly decreased within 2 weeks after remodeling. The TVOC level showed a decrease at week 2 but increased again at weeks 6 and 10. The reduction of pruritus and EASI score was statistically significant in patients whose baseline EASI score was >3.

CONCLUSION

Replacing the wallpaper and flooring of houses with environmentally friendly material reduced FA in ambient air and improved pruritus and the severity of atopic eczema. The improvement of pruritus and eczema was statistically significant in patients whose baseline EASI score was >3.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Williams H, Flohr C. How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006; 118:209–213.

Article2. Herbarth O, Fritz GJ, Rehwagen M, Richter M, Röder S, Schlink U. Association between indoor renovation activities and eczema in early childhood. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2006; 209:241–247.

Article3. Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Krämer U, et al. Atopic diseases, allergic sensitization, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008; 177:1331–1337.

Article4. Arnedo-Pena A, García-Marcos L, Carvajal Urueña I, Busquets Monge R, Morales Suárez-Varela M, Miner Canflanca I, et al. Air pollution and recent symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in schoolchildren aged between 6 and 7 years. Arch Bronconeumol. 2009; 45:224–229.

Article5. Matsunaga I, Miyake Y, Yoshida T, Miyamoto S, Ohya Y, Sasaki S, et al. Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study Group. Ambient formaldehyde levels and allergic disorders among Japanese pregnant women: baseline data from the Osaka maternal and child health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2008; 18:78–84.

Article6. Wen HJ, Chen PC, Chiang TL, Lin SJ, Chuang YL, Guo YL. Predicting risk for early infantile atopic dermatitis by hereditary and environmental factors. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:1166–1172.

Article7. Ukawa S, Araki A, Kanazawa A, Yuasa M, Kishi R. The relationship between atopic dermatitis and indoor environmental factors: a cross-sectional study among Japanese elementary school children. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013; 86:777–787.

Article8. Choi DW, Moon KW, Byeon SH, Lee EI, Sul DG, Lee JH, et al. Indoor volatile organic compounds in atopy patients' houses in South Korea. Indoor Built Environ. 2009; 18:144–154.

Article9. Park HC, Kim YH, Kim JE, Ko JY, Nam Goung SJ, Lee CM, et al. Effect of air purifier on indoor air quality and atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2013; 1:248–256.

Article10. Kim JH, Lee KM, Koh SB, Kim SH, Choi EH. Effect of polyurushiol paint on indoor air quality and atopic dermatitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2010; 48:198–205.11. Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol. 2001; 10:11–18.

Article12. Hodgson AT, Rudd AF, Beal D, Chandra S. Volatile organic compound concentrations and emission rates in new manufactured and site-built houses. Indoor Air. 2000; 10:178–192.

Article13. Bernstein JA, Alexis N, Bacchus H, Bernstein IL, Fritz P, Horner E, et al. The health effects of non-industrial indoor air pollution. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:585–591.

Article14. Wang S, Ang HM, Tade MO. Volatile organic compounds in indoor environment and photocatalytic oxidation: state of the art. Environ Int. 2007; 33:694–705.

Article15. Eberlein-König B, Przybilla B, Kühnl P, Pechak J, Gebefügi I, Kleinschmidt J, et al. Influence of airborne nitrogen dioxide or formaldehyde on parameters of skin function and cellular activation in patients with atopic eczema and control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998; 101:141–143.

Article16. Barro R, Regueiro J, Llompart M, Garcia-Jares C. Analysis of industrial contaminants in indoor air: part 1. Volatile organic compounds, carbonyl compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls. J Chromatogr A. 2009; 1216:540–566.

Article17. Saito A, Tanaka H, Usuda H, Shibata T, Higashi S, Yamashita H, et al. Characterization of skin inflammation induced by repeated exposure of toluene, xylene, and formaldehyde in mice. Environ Toxicol. 2011; 26:224–232.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Improvement of Atopic Dermatitis Severity after Reducing Indoor Air Pollutants

- Effect of air purifier on indoor air quality and atopic dermatitis

- Effect of Polyurushiol Paint on Indoor Air Quality and Atopic Dermatitis

- Case Report of a Pilot with Atopic Dermatitis

- Effect of the indoor environment on atopic dermatitis in children