Korean Circ J.

2007 May;37(5):196-201. 10.4070/kcj.2007.37.5.196.

Gender Differences in the Role of Serum Uric Acid for Predicting Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiology, Heart Center, Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea. jhbae@kyuh.co.kr

- KMID: 2227064

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2007.37.5.196

Abstract

-

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Serum uric acid has been reported to be an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) and a predictor of mortality in patients with CAD. Yet there is gender difference for the serum uric acid levels. We evaluated the influence of the uric acid levels on major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in patients with CAD according to their gender.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

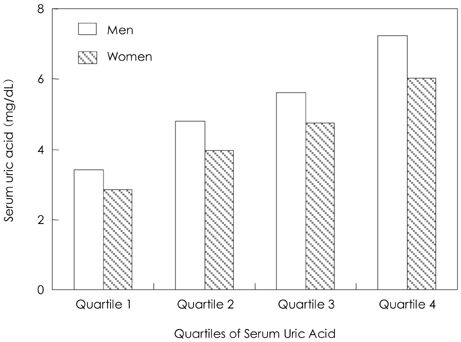

Of the 777 patients with angiographically proven CAD, 660 patients (378 males, 57.3%) were followed up a median of 18 month (maximum: 61 month). The MACEs included acute myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous coronary intervention due to de novo lesion during follow up, new onset congestive heart failure and sudden cardiac death.

RESULTS

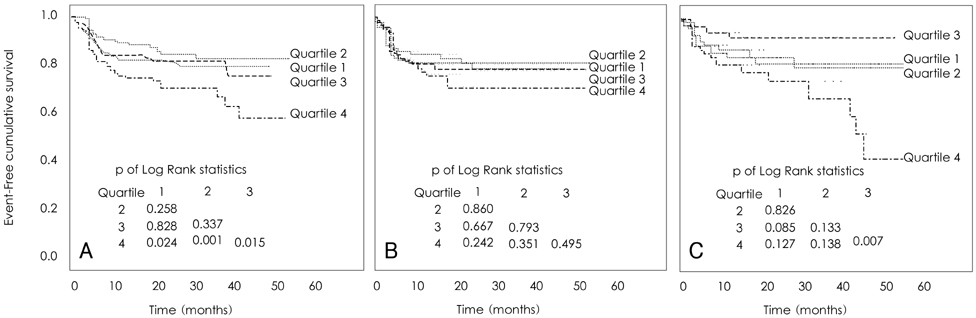

MACEs in men were associated with acute coronary syndrome (ACS)(odds ratio (OR): 2.03, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.01 to 3.96, p=0.038), multi-vessel disease (OR: 3.68, 95% CI: 1.82 to 7.47, p=0.000) and the serum uric acid levels (OR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.50, p=0.044), according to multivariate Cox regression analysis. For women, MACEs were associated with multi-vessel disease (OR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.15 to 5.13, p=0.020) and the highest uric acid quartile (OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.31 to 5.30, p=0.006) according to multivariate Cox regression analysis. For all patients, the highest uric acid quartile was associated with an increased risk of MACE (p=0.000), and CHF was the major contributor to the observed MACEs (p=0.004).

CONCLUSION

In male patients with CAD, the serum uric acid level is a predictor of cardiovascular events, and the highest uric acid quartile is a predictor of cardiovascular events in women.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hare JM, Johnson RJ. Uric acid predicts clinical outcomes in heart failure: insights regarding the role of xanthine oxidase and uric acid in disease pathophysiology. Circulation. 2003. 107:1951–1953.2. Mercuro G, Vitale C, Cerquetani E, et al. Effect of hyperuricemia upon endothelial function in patients at increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2004. 94:932–935.3. Ward HJ. Uric acid as an independent risk factor in the treatment of hypertension. Lancet. 1998. 352:670–671.4. Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Rossi A, et al. Elevated serum uric acid levels are associated with diastolic dysfunction in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2002. 143:1107–1111.5. Bickel C, Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, et al. Serum uric acid as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2002. 89:12–17.6. Kojima S, Sakamoto T, Ishihara M, et al. Prognostic usefulness of serum uric acid after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005. 96:489–495.7. Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, et al. Uric acid and survival in chronic heart failure: validation and application in metabolic, functional, and hemodynamic staging. Circulation. 2003. 107:1991–1997.8. Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death. Ann Intern Med. 1999. 131:7–13.9. Moriarity JT, Folsom AR, Iribarren C, Nieto FJ, Rosamond WD. Serum uric acid and risk of coronary heart disease. Ann Epidemiol. 2000. 10:136–143.10. Tuttle KR, Short RA, Johnson RJ. Sex differences in uric acid and risk factors for coronary artery diseae. Am J Cardiol. 2001. 87:1411–1414.11. Rich MW. Uric acid: is it a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Am J Cardiol. 2000. 85:1018–1021.12. Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S, Kivlighn S. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular events in successfully treated hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999. 34:144–150.13. McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985. 312:159–163.14. Prendergast BD, Sagach VF, Shah AM. Basal release of nitric oxide augments the Frank-Starling response in the isolated heart. Circulation. 1997. 96:1320–1329.15. Lee JS, Park HG, Lee YM, Lee YW, Kim SW, Song CS. Observation of the serum uric acid in essential hypertension. Korean Circ J. 1987. 17:159–167.16. Yoo TW, Sung KC, Kim YC, et al. The relation of the hypertension, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome in the serum uric acid level. Korean Circ J. 2004. 34:874–882.17. Nicholls A, Snaith ML, Scot JT. Effect of oestrogen theraphy on plasma and urinary levels of uric acid. Br Med J. 1973. 1:449–451.18. Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Gunter EW, Byers T. Relation of serum uric acid to mortality and ischemic heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1995. 141:637–644.19. Bengtsson C, Lapidus L, Stendahl C, Waldenstrom J. Hyperuricemia and risk of cardiovascular disease and overall death: a 12-year follow-up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Acta Med Scand. 1988. 224:549–555.20. Morise AP. Assessment of estrogen status as a marker of prognosis in women with symptome of suspected coronary artery disease presenting for stress testing. Am J Cardiol. 2006. 97:367–371.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Serum Uric Acid is Associated with Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

- Does Hyperuricemia Play a Causative Role in the Development and/or Aggravation of Renal, Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease?

- Association of serum uric acid level with coronary artery stenosis severity in Korean end-stage renal disease patients

- Interrelationship of Uric Acid, Gout, and Metabolic Syndrome: Focus on Hypertension, Cardiovascular Disease, and Insulin Resistance

- Uric Acid and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Longitudinal Cohort Study