Clin Orthop Surg.

2015 Mar;7(1):77-84. 10.4055/cios.2015.7.1.77.

The Importance of Proximal Fusion Level Selection for Outcomes of Multi-Level Lumbar Posterolateral Fusion

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. spinecjh@gmail.com

- KMID: 2069878

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2015.7.1.77

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

There are few studies about risk factors for poor outcomes from multi-level lumbar posterolateral fusion limited to three or four level lumbar posterolateral fusions. The purpose of this study was to analyze the outcomes of multi-level lumbar posterolateral fusion and to search for possible risk factors for poor surgical outcomes.

METHODS

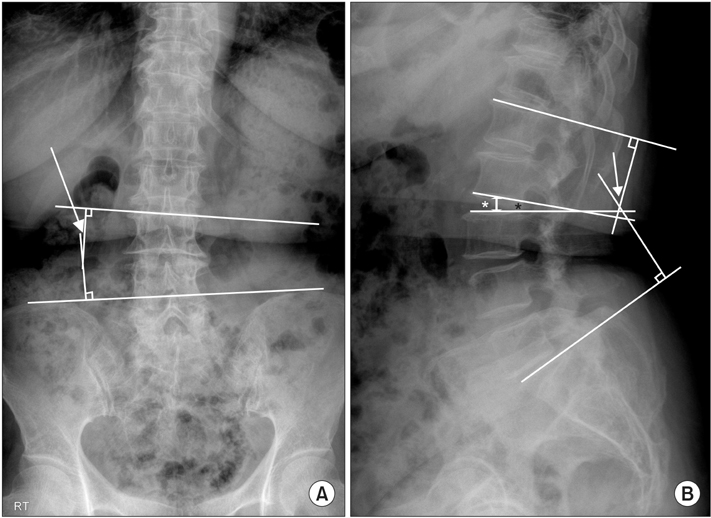

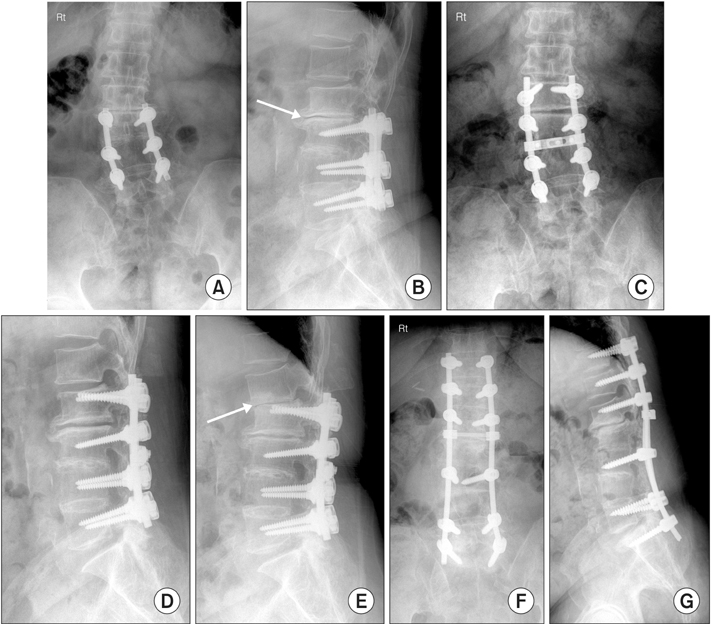

We retrospectively analyzed 37 consecutive patients who underwent multi-level lumbar or lumbosacral posterolateral fusion with posterior instrumentation. The outcomes were deemed either 'good' or 'bad' based on clinical and radiological results. Many demographic and radiological factors were analyzed to examine potential risk factors for poor outcomes. Student t-test, Fisher exact test, and the chi-square test were used based on the nature of the variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to exclude confounding factors.

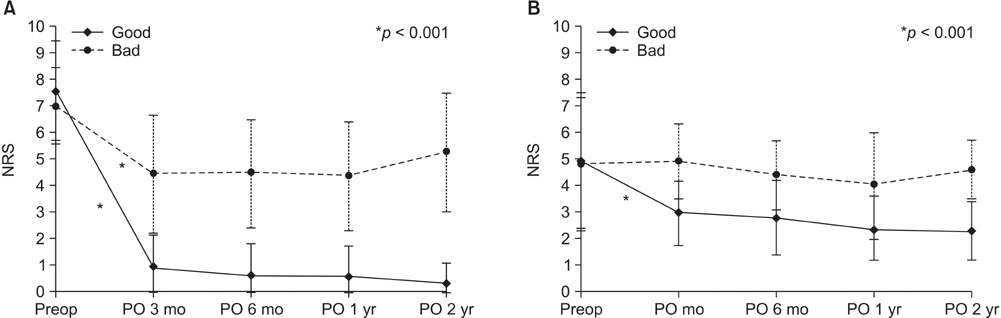

RESULTS

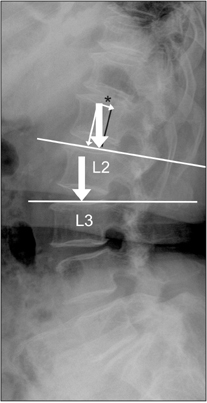

Twenty cases showed a good outcome (group A, 54.1%) and 17 cases showed a bad outcome (group B, 45.9%). The overall fusion rate was 70.3%. The revision procedures (group A: 1/20, 5.0%; group B: 4/17, 23.5%), proximal fusion to L2 (group A: 5/20, 25.0%; group B: 10/17, 58.8%), and severity of stenosis (group A: 12/19, 63.3%; group B: 3/11, 27.3%) were adopted as possible related factors to the outcome in univariate analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that only the proximal fusion level (superior instrumented vertebra, SIV) was a significant risk factor. The cases in which SIV was L2 showed inferior outcomes than those in which SIV was L3. The odds ratio was 6.562 (95% confidence interval, 1.259 to 34.203).

CONCLUSIONS

The overall outcome of multi-level lumbar or lumbosacral posterolateral fusion was not as high as we had hoped it would be. Whether the SIV was L2 or L3 was the only significant risk factor identified for poor outcomes in multi-level lumbar or lumbosacral posterolateral fusion in the current study. Thus, the authors recommend that proximal fusion levels be carefully determined when multi-level lumbar fusions are considered.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Aiki H, Ohwada O, Kobayashi H, et al. Adjacent segment stenosis after lumbar fusion requiring second operation. J Orthop Sci. 2005; 10(5):490–495.

Article2. Ekman P, Moller H, Hedlund R. The long-term effect of posterolateral fusion in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: a randomized controlled study. Spine J. 2005; 5(1):36–44.

Article3. Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004; 29(17):1938–1944.

Article4. Turunen V, Nyyssonen T, Miettinen H, et al. Lumbar instrumented posterolateral fusion in spondylolisthetic and failed back patients: a long-term follow-up study spanning 11-13 years. Eur Spine J. 2012; 21(11):2140–2148.

Article5. Inage K, Ohtori S, Koshi T, et al. One, two-, and three-level instrumented posterolateral fusion of the lumbar spine with a local bone graft: a prospective study with a 2-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011; 36(17):1392–1396.

Article6. Dehoux E, Fourati E, Madi K, Reddy B, Segal P. Posterolateral versus interbody fusion in isthmic spondylolisthesis: functional results in 52 cases with a minimum follow-up of 6 years. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004; 70(6):578–582.7. Madan S, Boeree NR. Outcome of posterior lumbar interbody fusion versus posterolateral fusion for spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002; 27(14):1536–1542.

Article8. Farrokhi MR, Rahmanian A, Masoudi MS. Posterolateral versus posterior interbody fusion in isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Neurotrauma. 2012; 29(8):1567–1573.

Article9. Gehrchen PM, Dahl B, Katonis P, Blyme P, Tondevold E, Kiaer T. No difference in clinical outcome after posterolateral lumbar fusion between patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis and those with degenerative disc disease using pedicle screw instrumentation: a comparative study of 112 patients with 4 years of follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2002; 11(5):423–427.

Article10. Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Bullis D, Betz RR, Baldus C, Schoenecker PL. Results of in situ fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992; 5(4):433–442.

Article11. Schizas C, Theumann N, Burn A, et al. Qualitative grading of severity of lumbar spinal stenosis based on the morphology of the dural sac on magnetic resonance images. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010; 35(21):1919–1924.

Article12. Lee CS, Hwang CJ, Lee SW, et al. Risk factors for adjacent segment disease after lumbar fusion. Eur Spine J. 2009; 18(11):1637–1643.

Article13. Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26(17):1873–1878.

Article14. Cho KJ, Suk SI, Park SR, Kim JH, Jung JH. Selection of proximal fusion level for adult degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2013; 22(2):394–401.

Article15. Geisler FH, Guyer RD, Blumenthal SL, et al. Patient selection for lumbar arthroplasty and arthrodesis: the effect of revision surgery in a controlled, multicenter, randomized study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008; 8(1):13–16.

Article16. Kim YJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Rhim S, Kim YW. Is the T9, T11, or L1 the more reliable proximal level after adult lumbar or lumbosacral instrumented fusion to L5 or S1? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007; 32(24):2653–2661.

Article17. Lee JC, Kim MS, Shin BJ. An analysis of the prognostic factors affecing the clinical outcomes of conventional lumbar open discectomy: clinical and radiological prognostic factors. Asian Spine J. 2010; 4(1):23–31.

Article18. Lewis SJ, Abbas H, Chua S, et al. Upper instrumented vertebral fractures in long lumbar fusions: what are the associated risk factors? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012; 37(16):1407–1414.19. Christensen FB, Thomsen K, Eiskjaer SP, Gelinick J, Bunger CE. Functional outcome after posterolateral spinal fusion using pedicle screws: comparison between primary and salvage procedure. Eur Spine J. 1998; 7(4):321–327.

Article20. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong KL, et al. Infection risk for primary and revision instrumented lumbar spine fusion in the Medicare population. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012; 17(4):342–347.

Article21. Min JH, Jang JS, Jung BJ, et al. The clinical characteristics and risk factors for the adjacent segment degeneration in instrumented lumbar fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008; 21(5):305–309.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison Between Allograft Mixed with Local Bone and Autograft in Posterolateral Lumbar Fusion

- Comparison between Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion with Pedicle Screw Fixation and Posterolateral Fusion with Pedicle Screw Fixation in Spondylolytic Spondylolisthesis in Adults

- Comparison between Posterolateral Fusion with Pedicle Screw Fixation and Anterior Interbody Fusion with Pedicle Screw Fixation in Spondylolytic Spondylolisthesis of the Lumbar Spine

- The Result of the Posterolateral Fusion with Knodt Rod and without Knodt Rod in Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis of the Lumbar Spine

- Change of Segmental Motion After Lumbar Posterolateral Fusion