J Korean Med Assoc.

2013 Sep;56(9):771-777. 10.5124/jkma.2013.56.9.771.

Propofol abuse among healthcare professionals

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. shhong7272@gmail.com

- KMID: 2015673

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2013.56.9.771

Abstract

- The number of healthcare professionals (HCPs) abusing propofol has been steadily growing, while recreational use of propofol among the general public has become a social concern. Propofol was once believed to be unsuited for the purpose of abuse because it wears off too quickly and induces unconsciousness more frequently than euphoria. However, studies have demonstrated the abuse potential of propofol. Animal studies have shown that propofol increases dopamine levels in the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is a putative mechanism of addiction for most addictive drugs. Behavior studies, not only with animals but also with human beings, have demonstrated that administration of propofol induces conditioned rewards and reinforcement. Although the incidence of propofol abuse among HCPs seems to be lower than that of abuse of common addictive substances, multiple articles and case reports have documented cases. Easy access to the drug is closely associated with its abuse among HCPs. In addition, the pharmacologic properties of propofol, specifically its short onset and offset, is one of reasons HCPs start to abuse this drug without any serious consideration and makes propofol abuse difficult to detect. To reduce propofol abuse among HCPs, we should develop a strict pharmacy control system for limiting access to propofol. Adopting radio-frequency identification system for controlled drugs could be an effective option. However, substance dependent HCPs are quite resourceful even in obtaining controlled drugs. Therefore, a multilateral approach to stem the rising tide of propofol abuse among HCPs is needed: a combination of preventative education, early identification and intervention, aggressive treatment, and consistent rehabilitation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Healthcare providers have to be careful with drug abuse in Korea

Jaemin Lee

J Korean Med Assoc. 2013;56(9):752-754. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2013.56.9.752.

Reference

-

1. Follette JW, Farley WJ. Anesthesiologist addicted to propofol. Anesthesiology. 1992; 77:817–818.

Article2. Wilson C, Canning P, Caravati EM. The abuse potential of propofol. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010; 48:165–170.

Article3. Park JH, Kim HJ, Seo JS. Medicolegal review of deaths related to propofol administration: analysis of 36 autopsied cases. Korean J Leg Med. 2012; 36:56–62.

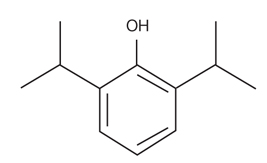

Article4. Jung YJ. The number of doctors arrested for drug-related of-fences increased by 64%. The Munwha Ilbo. 2012. 08. 14.5. Wikimedia Commons. File:Propofol.svg [Internet]. [place unknown]: MediaWiki.org;cited 2013 Jul 8. Available from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Propofol.svg.6. Trapani G, Altomare C, Liso G, Sanna E, Biggio G. Propofol in anesthesia. Mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, and drug delivery. Curr Med Chem. 2000; 7:249–271.

Article7. Krasowski MD, Koltchine VV, Rick CE, Ye Q, Finn SE, Harrison NL. Propofol and other intravenous anesthetics have sites of action on the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor distinct from that for isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol. 1998; 53:530–538.

Article8. Lee YS. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs for sedation. J Korean Med Assoc. 2013; 56:279–284.

Article9. Lee JW, Lee KY. Safe sedation in a private clinic. J Korean Med Assoc. 2011; 54:1179–1188.

Article10. Tan KR, Rudolph U, Lüscher C. Hooked on benzodiazepines: GABAA receptor subtypes and addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2011; 34:188–197.

Article11. Pain L, Gobaille S, Schleef C, Aunis D, Oberling P. In vivo dopamine measurements in the nucleus accumbens after nonanesthetic and anesthetic doses of propofol in rats. Anesth Analg. 2002; 95:915–919.

Article12. Keita H, Lecharny JB, Henzel D, Desmonts JM, Mantz J. Is inhibition of dopamine uptake relevant to the hypnotic action of i.v. anaesthetics? Br J Anaesth. 1996; 77:254–256.

Article13. Roussin A, Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Pharmacological and clinical evidences on the potential for abuse and dependence of propofol: a review of the literature. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007; 21:459–466.

Article14. Pain L, Oberling P, Sandner G, Di Scala G. Effect of propofol on affective state as assessed by place conditioning paradigm in rats. Anesthesiology. 1996; 85:121–128.

Article15. Pain L, Oberling P, Sandner G, Di Scala G. Effect of midazolam on propofol-induced positive affective state assessed by place conditioning in rats. Anesthesiology. 1997; 87:935–943.

Article16. LeSage MG, Stafford D, Glowa JR. Abuse liability of the anesthetic propofol: self-administration of propofol in rats under fixed-ratio schedules of drug delivery. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000; 153:148–154.

Article17. Weerts EM, Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Comparison of the intravenous reinforcing effects of propofol and methohexital in baboons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999; 57:51–60.

Article18. Zacny JP, Lichtor JL, Thompson W, Apfelbaum JL. Propofol at a subanesthetic dose may have abuse potential in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg. 1993; 77:544–552.

Article19. US Department of Health and Human Services. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings [Internet]. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration;2012. cited 2013 Jul 8. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/Index.aspx.20. Baldisseri MR. Impaired healthcare professional. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:2 Suppl. S106–S116.

Article21. Hughes PH, Brandenburg N, Baldwin DC Jr, Storr CL, Williams KM, Anthony JC, Sheehan DV. Prevalence of substance use among US physicians. JAMA. 1992; 267:2333–2339.

Article22. Beaujouan L, Czernichow S, Pourriat JL, Bonnet F. Prevalence and risk factors for substance abuse and dependence among anaesthetists: a national survey. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2005; 24:471–479.23. Wischmeyer PE, Johnson BR, Wilson JE, Dingmann C, Bachman HM, Roller E, Tran ZV, Henthorn TK. A survey of propofol abuse in academic anesthesia programs. Anesth Analg. 2007; 105:1066–1071.

Article24. Hong SH. Drug abuse associated with procedural sedation. J Korean Med Assoc. 2013; 56:292–298.

Article25. Stocks G. Abuse of propofol by anesthesia providers: the case for re-classification as a controlled substance. J Addict Nurs. 2011; 22:57–62.

Article26. Lee S, Lee MS, Kim YA, Ahn W, Lee HC. Propofol abuse of the medical personnel in operation room in Korea. Korean J Leg Med. 2010; 34:101–107.27. Kintz P, Villain M, Dumestre V, Cirimele V. Evidence of addiction by anesthesiologists as documented by hair analysis. Forensic Sci Int. 2005; 153:81–84.

Article28. Kim JH. Sharp increase in propofol thefts. Health Korea News. 2012. 10. 11.29. Domino KB, Hornbein TF, Polissar NL, Renner G, Johnson J, Alberti S, Hankes L. Risk factors for relapse in health care professionals with substance use disorders. JAMA. 2005; 293:1453–1460.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Propofol abuse among healthcare workers: an analysis of criminal cases using the database of the Supreme Court of South Korea’s judgments

- Propofol Abuse in Professionals

- Fatal Factors Related to Abuse of Propofol (Diprivan) A Case Report and Review of the Literature

- Clinical and psychological characteristics of propofol abusers in Korea: a survey of propofol abuse in 38, non-healthcare professionals

- A comprehensive analysis of propofol abuse, addiction and neuropharmacological aspects: an updated review