Int J Stem Cells.

2024 Feb;17(1):51-58. 10.15283/ijsc23172.

Host-Microbe Interactions Regulate Intestinal Stem Cells and Tissue Turnover in Drosophila

- Affiliations

-

- 1National Creative Research Initiative Center for Hologenomics and School of Biological Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2The Research Institute of Basic Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2552017

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc23172

Abstract

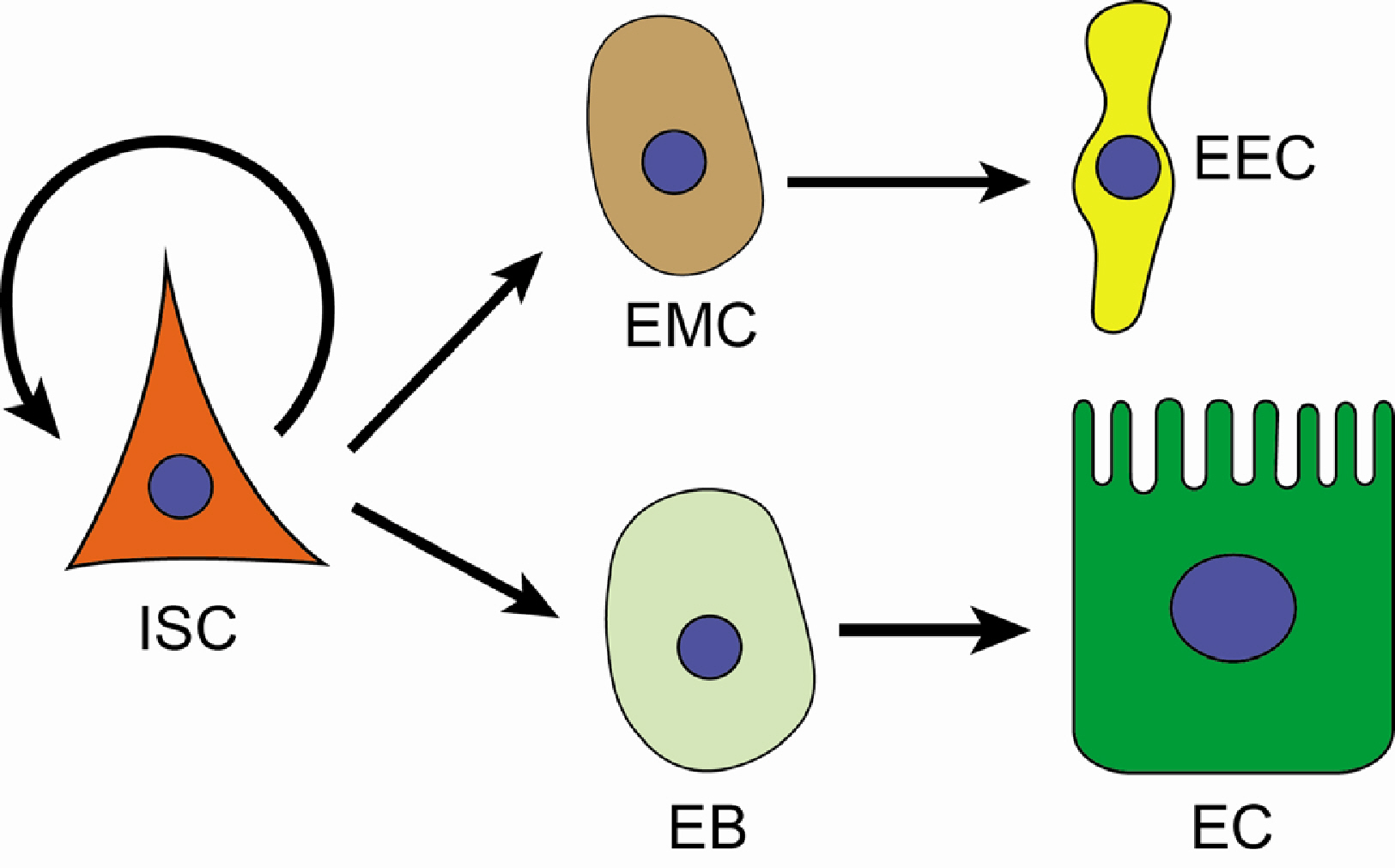

- With the activity of intestinal stem cells and continuous turnover, the gut epithelium is one of the most dynamic tissues in animals. Due to its simple yet conserved tissue structure and enteric cell composition as well as advanced genetic and histologic techniques, Drosophila serves as a valuable model system for investigating the regulation of intestinal stem cells. The Drosophila gut epithelium is in constant contact with indigenous microbiota and encounters externally introduced “non-self” substances, including foodborne pathogens. Therefore, in addition to its role in digestion and nutrient absorption, another essential function of the gut epithelium is to control the expansion of microbes while maintaining its structural integrity, necessitating a tissue turnover process involving intestinal stem cell activity. As a result, the microbiome and pathogens serve as important factors in regulating intestinal tissue turnover. In this manuscript, I discuss crucial discoveries revealing the interaction between gut microbes and the host’s innate immune system, closely associated with the regulation of intestinal stem cell proliferation and differentiation, ultimately contributing to epithelial homeostasis.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Leblond CP, Walker BE. 1956; Renewal of cell populations. Physiol Rev. 36:255–276. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.1956.36.2.255. PMID: 13322651.

Article2. Ohlstein B, Spradling A. 2006; The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 439:470–474. DOI: 10.1038/nature04333. PMID: 16340960.

Article3. Micchelli CA, Perrimon N. 2006; Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature. 439:475–479. DOI: 10.1038/nature04371. PMID: 16340959.

Article4. O'Brien LE, Soliman SS, Li X, Bilder D. 2011; Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell. 147:603–614. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048. PMID: 22036568. PMCID: PMC3246009.5. Lee JH, Lee KA, Lee WJ. 2017; Microbiota, gut physiology, and insect immunity. Adv Insect Physiol. 52:111–138. DOI: 10.1016/bs.aiip.2016.11.001.

Article6. Zwick RK, Ohlstein B, Klein OD. 2019; Intestinal renewal across the animal kingdom: comparing stem cell activity in mouse and Drosophila. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 316:G313–G322. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00353.2018. PMID: 30543448. PMCID: PMC6415738.7. Cheng H, Leblond CP. 1974; Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat. 141:537–561. DOI: 10.1002/aja.1001410407. PMID: 4440635.

Article8. Gehart H, Clevers H. 2019; Tales from the crypt: new insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:19–34. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-018-0081-y. PMID: 30429586.

Article9. Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. 2007; Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 449:1003–1007. DOI: 10.1038/nature06196. PMID: 17934449.

Article10. Clevers H. 2013; The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell com-partment. Cell. 154:274–284. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004. PMID: 23870119.

Article11. Marianes A, Spradling AC. 2013; Physiological and stem cell compartmentalization within the Drosophila midgut. Elife. 2:e00886. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.00886. PMID: 23991285. PMCID: PMC3755342. PMID: 80c1aebad3164d62b0386dfbb28c99ed.

Article12. Buchon N, Osman D, David FP, et al. 2013; Morphological and molecular characterization of adult midgut compartmentalization in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 3:1725–1738. Erratum in: Cell Rep 2013;3:1755. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.001. PMID: 23643535. PMID: fb0f67a4b21a4637aebfd0877393e0c8.

Article13. Guo Z, Ohlstein B. 2015; Stem cell regulation. Bidirectional Notch signaling regulates Drosophila intestinal stem cell multipotency. Science. 350:aab0988. DOI: 10.1126/science.aab0988. PMID: 26586765. PMCID: PMC5431284.

Article14. Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. 2011; Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002272. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272. PMID: 21966276. PMCID: PMC3178584. PMID: e142be8be0ef442ebe1e6a018a47e07b.15. Ryu JH, Kim SH, Lee HY, et al. 2008; Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science. 319:777–782. DOI: 10.1126/science.1149357. PMID: 18218863.

Article16. Cox CR, Gilmore MS. 2007; Native microbial colonization of Drosophila melanogaster and its use as a model of Enterococcus faecalis pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 75:1565–1576. DOI: 10.1128/IAI.01496-06. PMID: 17220307. PMCID: PMC1865669.

Article17. Ren C, Webster P, Finkel SE, Tower J. 2007; Increased internal and external bacterial load during Drosophila aging without life-span trade-off. Cell Metab. 6:144–152. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.006. PMID: 17681150.

Article18. Storelli G, Defaye A, Erkosar B, Hols P, Royet J, Leulier F. 2011; Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. 14:403–414. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012. PMID: 21907145.

Article19. Clark RI, Walker DW. 2018; Role of gut microbiota in aging-related health decline: insights from invertebrate models. Cell Mol Life Sci. 75:93–101. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-017-2671-1. PMID: 29026921. PMCID: PMC5754256.

Article20. Sharon G, Segal D, Ringo JM, Hefetz A, Zilber-Rosenberg I, Rosenberg E. 2010; Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:20051–20056. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:4853. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1009906107. PMID: 21041648. PMCID: PMC2993361.

Article21. Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, et al. 2011; Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 334:670–674. DOI: 10.1126/science.1212782. PMID: 22053049.

Article22. Lee KA, Kim SH, Kim EK, et al. 2013; Bacterial-derived uracil as a modulator of mucosal immunity and gut-microbe homeostasis in Drosophila. Cell. 153:797–811. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.009. PMID: 23663779.

Article23. Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. 2009; Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 4:49–61. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016. PMID: 19128792. PMCID: PMC2659574.

Article24. Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. 2009; Inva-sive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 23:2333–2344. DOI: 10.1101/gad.1827009. PMID: 19797770. PMCID: PMC2758745.

Article25. Lemaitre B, Kromer-Metzger E, Michaut L, et al. 1995; A rece-ssive mutation, immune deficiency (imd), defines two distinct control pathways in the Drosophila host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92:9465–9469. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9465. PMID: 7568155. PMCID: PMC40822.

Article26. Choe KM, Werner T, Stöven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV. 2002; Requirement for a peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) in Relish activation and antibacterial immune responses in Drosophila. Science. 296:359–362. DOI: 10.1126/science.1070216. PMID: 11872802.

Article27. Gottar M, Gobert V, Michel T, Belvin M, Duyk G, Hoff-mann JA, et al. 2002; The Drosophila immune response against Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by a peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature. 416:640–644. DOI: 10.1038/nature734. PMID: 11912488.

Article28. Rämet M, Manfruelli P, Pearson A, Mathey-Prevot B, Ezekowitz RA. 2002; Functional genomic analysis of phagocytosis and identification of a Drosophila receptor for E. coli. Nature. 416:644–648. DOI: 10.1038/nature735. PMID: 11912489.

Article29. Bosco-Drayon V, Poidevin M, Boneca IG, Narbonne-Reveau K, Royet J, Charroux B. 2012; Peptidoglycan sensing by the receptor PGRP-LE in the Drosophila gut induces immune responses to infectious bacteria and tolerance to micro-biota. Cell Host Microbe. 12:153–165. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.002. PMID: 22901536.

Article30. Myllymäki H, Valanne S, Rämet M. 2014; The Drosophila imd signaling pathway. J Immunol. 192:3455–3462. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309. PMID: 24706930.31. Wang L, Ryoo HD, Qi Y, Jasper H. 2015; PERK limits Drosophila lifespan by promoting intestinal stem cell proliferation in response to ER stress. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005220. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005220. PMID: 25945494. PMCID: PMC4422665. PMID: 5194a7b1d20d41df94272189b2f4cf56.32. Guo L, Karpac J, Tran SL, Jasper H. 2014; PGRP-SC2 promotes gut immune homeostasis to limit commensal dysbiosis and extend lifespan. Cell. 156:109–122. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.018. PMID: 24439372. PMCID: PMC3928474.

Article33. Jiang H, Patel PH, Kohlmaier A, Grenley MO, McEwen DG, Edgar BA. 2009; Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 137:1343–1355. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. PMID: 19563763. PMCID: PMC2753793.

Article34. Houtz P, Bonfini A, Liu X, et al. 2017; Hippo, TGF-β, and Src-MAPK pathways regulate transcription of the upd3 cytokine in Drosophila enterocytes upon bacterial infection. PLoS Genet. 13:e1007091. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007091. PMID: 29108021. PMCID: PMC5690694. PMID: ebd0d56077be4cbda62ca7c5ec914237.35. Iatsenko I, Boquete JP, Lemaitre B. 2018; Microbiota-derived lactate activates production of reactive oxygen species by the intestinal NADPH oxidase Nox and shortens Drosophila lifespan. Immunity. 49:929–942.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.017. PMID: 30446385.

Article36. Ha EM, Oh CT, Bae YS, Lee WJ. 2005; A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. 310:847–850. DOI: 10.1126/science.1117311. PMID: 16272120.

Article37. Ha EM, Lee KA, Seo YY, et al. 2009; Coordination of multiple dual oxidase-regulatory pathways in responses to commensal and infectious microbes in drosophila gut. Nat Immunol. 10:949–957. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1765. PMID: 19668222.

Article38. Ha EM, Oh CT, Ryu JH, et al. 2005; An antioxidant system required for host protection against gut infection in Droso-phila. Dev Cell. 8:125–132. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.007. PMID: 15621536.

Article39. Kim EK, Lee KA, Hyeon DY, et al. 2020; Bacterial nucleoside catabolism controls quorum sensing and commensal-to-pathogen transition in the Drosophila gut. Cell Host Mic-robe. 27:345–357.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.01.025. PMID: 32078802.40. Lee KA, Cho KC, Kim B, et al. 2018; Inflammation-modulated metabolic reprogramming is required for DUOX-dependent gut immunity in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe. 23:338–352.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.011. PMID: 29503179.41. Ren F, Wang K, Zhang T, Jiang J, Nice EC, Huang C. 2015; New insights into redox regulation of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1850:1518–1526. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.02.017. PMID: 25766871.

Article42. Owusu-Ansah E, Banerjee U. 2009; Reactive oxygen species prime Drosophila haematopoietic progenitors for differentiation. Nature. 461:537–541. DOI: 10.1038/nature08313. PMID: 19727075. PMCID: PMC4380287.

Article43. Hochmuth CE, Biteau B, Bohmann D, Jasper H. 2011; Redox regulation by Keap1 and Nrf2 controls intestinal stem cell proliferation in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 8:188–199. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.006. PMID: 21295275. PMCID: PMC3035938.

Article44. Xu C, Luo J, He L, Montell C, Perrimon N. 2017; Oxidative stress induces stem cell proliferation via TRPA1/RyR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in the Drosophila midgut. Elife. 6:e22441. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.22441. PMID: 28561738. PMCID: PMC5451214. PMID: 6312d8f93fe84ae29d51e7adafc1a184.

Article45. Basset A, Khush RS, Braun A, et al. 2000; The phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia carotovora infects Drosophila and activates an immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 97:3376–3381. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3376. PMID: 10725405. PMCID: PMC16247.

Article46. Basset A, Tzou P, Lemaitre B, Boccard F. 2003; A single gene that promotes interaction of a phytopathogenic bacterium with its insect vector, Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO Rep. 4:205–209. DOI: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor730. PMID: 12612613. PMCID: PMC1315828.

Article47. Quevillon-Cheruel S, Leulliot N, Muniz CA, et al. 2009; Evf, a virulence factor produced by the Drosophila pathogen Erwi-nia carotovora, is an S-palmitoylated protein with a new fold that binds to lipid vesicles. J Biol Chem. 284:3552–3562. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M808334200. PMID: 18978353.

Article48. Vodovar N, Vinals M, Liehl P, et al. 2005; Drosophila host defense after oral infection by an entomopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102:11414–11419. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0502240102. PMID: 16061818. PMCID: PMC1183552.

Article49. Liehl P, Blight M, Vodovar N, Boccard F, Lemaitre B. 2006; Prevalence of local immune response against oral infection in a Drosophila/Pseudomonas infection model. PLoS Pathog. 2:e56. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020056. PMID: 16789834. PMCID: PMC1475658. PMID: 4d2fa25fff9348febee6e86d119dc46b.50. Opota O, Vallet-Gély I, Vincentelli R, et al. 2011; Monalysin, a novel β-pore-forming toxin from the Drosophila pathogen Pseudomonas entomophila, contributes to host intestinal damage and lethality. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002259. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002259. PMID: 21980286. PMCID: PMC3182943. PMID: 38015d4decfb4c639a0ce5075303d43b.51. Chakrabarti S, Liehl P, Buchon N, Lemaitre B. 2012; Infection-induced host translational blockage inhibits immune respo-nses and epithelial renewal in the Drosophila gut. Cell Host Microbe. 12:60–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.001. PMID: 22817988.

Article52. Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2000; Establishment of Pseudo-monas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect. 2:1051–1060. DOI: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01259-4. PMID: 10967285.53. Grimont PA, Grimont F. 1978; The genus Serratia. Annu Rev Microbiol. 32:221–248. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.mi.32.100178.001253. PMID: 360966.54. Flyg C, Kenne K, Boman HG. 1980; Insect pathogenic properties of Serratia marcescens: phage-resistant mutants with a decreased resistance to Cecropia immunity and a decreased virulence to Drosophila. J Gen Microbiol. 120:173–181. DOI: 10.1099/00221287-120-1-173. PMID: 7012273.

Article55. Kurz CL, Chauvet S, Andrès E, et al. 2003; Virulence factors of the human opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens identified by in vivo screening. EMBO J. 22:1451–1460. DOI: 10.1093/emboj/cdg159. PMID: 12660152. PMCID: PMC152903.

Article56. Lee KZ, Lestradet M, Socha C, et al. 2016; Enterocyte purge and rapid recovery is a resilience reaction of the gut epithelium to pore-forming toxin attack. Cell Host Microbe. 20:716–730. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.010. PMID: 27889464.

Article57. Apidianakis Y, Pitsouli C, Perrimon N, Rahme L. 2009; Synergy between bacterial infection and genetic predisposition in intestinal dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106:20883–20888. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0911797106. PMID: 19934041. PMCID: PMC2791635.

Article58. Cronin SJ, Nehme NT, Limmer S, et al. 2009; Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies genes involved in intestinal pathogenic bacterial infection. Science. 325:340–343. DOI: 10.1126/science.1173164. PMID: 19520911. PMCID: PMC2975362.

Article59. Chatterjee M, Ip YT. 2009; Pathogenic stimulation of intestinal stem cell response in Drosophila. J Cell Physiol. 220:664–671. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.21808. PMID: 19452446. PMCID: PMC4003914.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Physiological understanding of host-microbial pathogen interactions in the gut

- Navigating the Landscape of Intestinal Regeneration: A Spotlight on Quiescence Regulation and Fetal Reprogramming

- From the Dish to the Real World: Modeling Interactions between the Gut and Microorganisms in Gut Organoids by Tailoring the Gut Milieu

- Epithelial-microbial diplomacy: escalating border tensions drive inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease

- Role of Intestinal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases