Korean Circ J.

2024 Jan;54(1):13-27. 10.4070/kcj.2023.0084.

Risk of Atrial Fibrillation and Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Center, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Medtronic Korea, Ltd., Seoul, Korea

- 5Liverpool Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Liverpool and Liverpool Chest and Heart Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 6Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark

- KMID: 2550600

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2023.0084

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

Comprehensive epidemiological data are lacking on the incident atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). This study aimed to examine the incidence, risk factors, and AF-related adverse outcomes of patients with CIEDs.

Methods

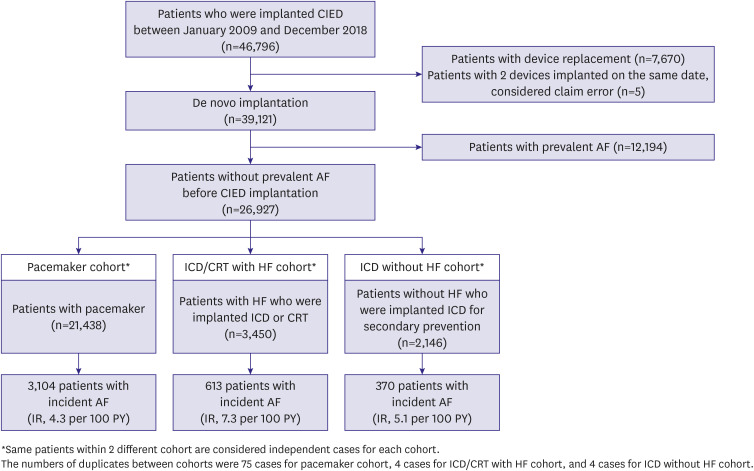

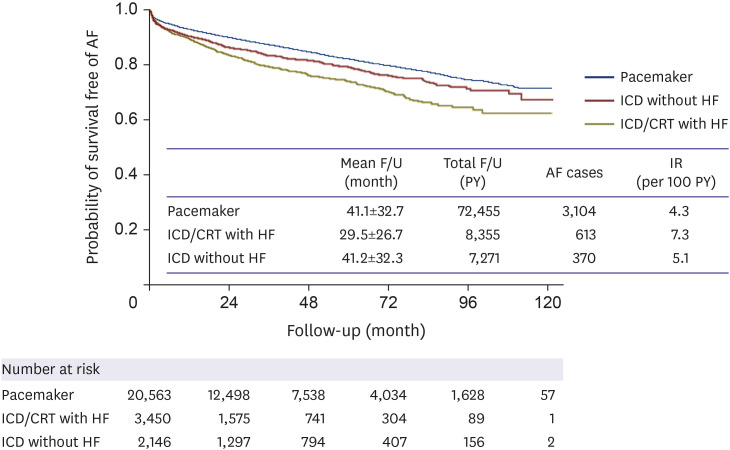

This was an observational cohort study that analyzed patients without prevalent AF who underwent CIED implantation in 2009–2018 using a Korean nationwide claims database. The subjects were divided into three groups by CIED type and indication: pacemaker (n=21,438), implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)/cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with heart failure (HF) (n=3,450), and ICD for secondary prevention without HF (n=2,146). The incidence of AF, AF-associated predictors, and adverse outcomes were evaluated.

Results

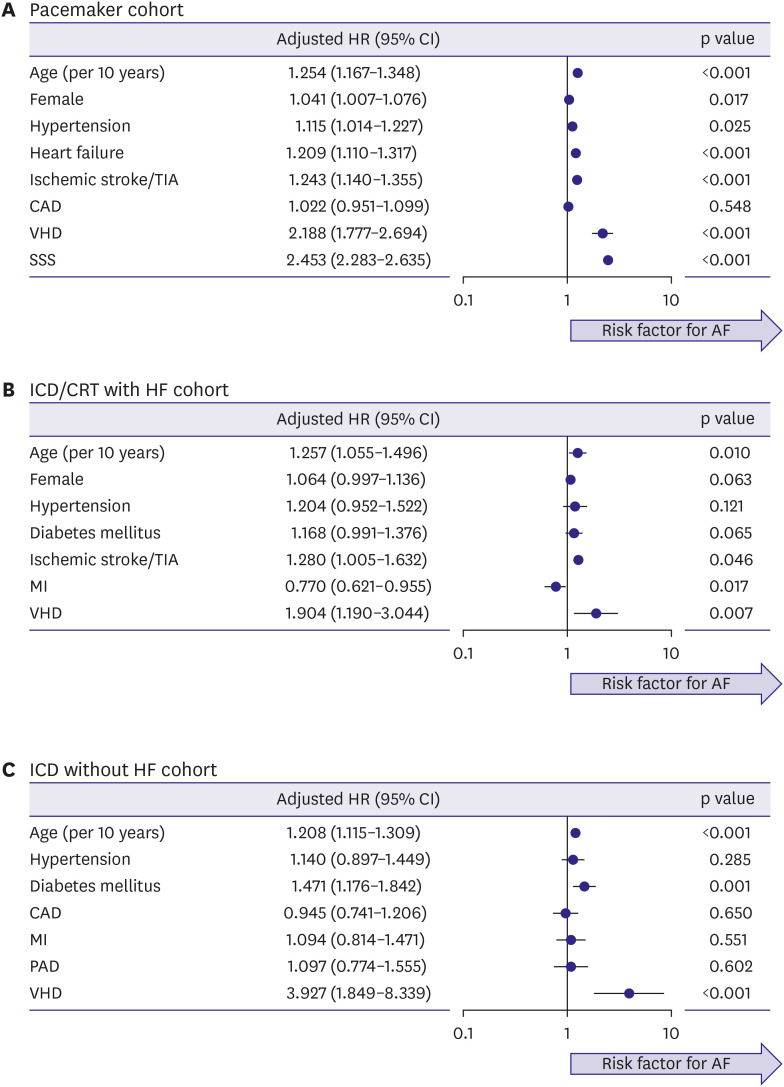

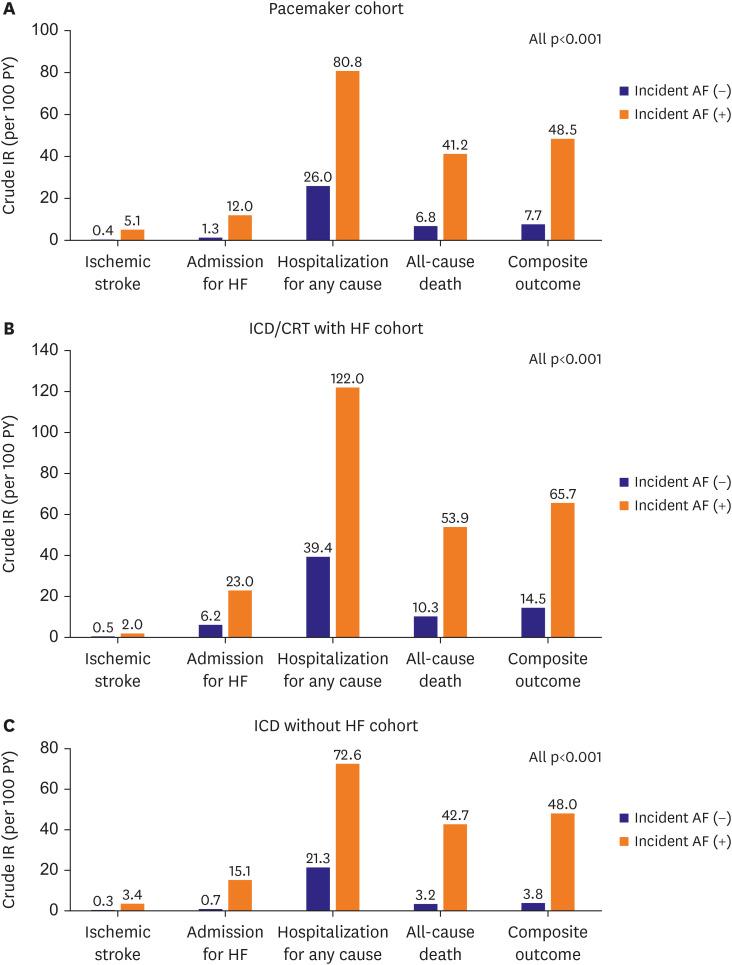

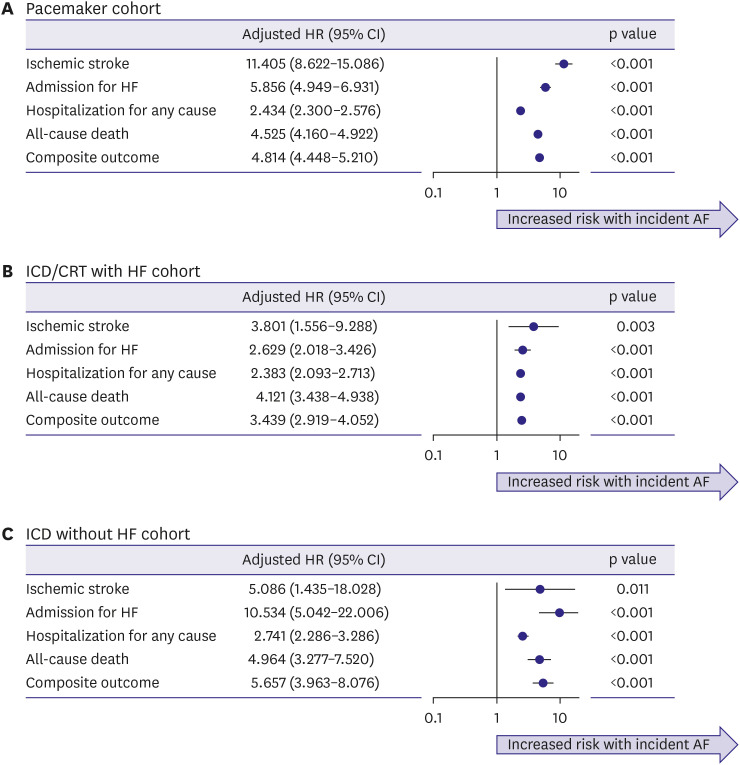

During follow-up, the incidence of AF was 4.3, 7.3, and 5.1 per 100 person-years in the pacemaker, ICD/CRT with HF, and ICD without HF cohorts, respectively. Across the three cohorts, older age and valvular heart disease were commonly associated with incident AF. Incident AF was consistently associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke (3.8–11.4-fold), admission for HF (2.6–10.5-fold), hospitalization for any cause (2.4–2.7-fold), all-cause death (4.1–5.0-fold), and composite outcomes (3.4–5.7-fold). Oral anticoagulation rates were suboptimal in patients with incident AF (pacemaker, 51.3%; ICD/CRT with HF, 51.7%; and ICD without HF, 33.8%, respectively).

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of patients implanted CIED developed newly diagnosed AF. Incident AF was associated with a higher risk of adverse events. The importance of awareness, early detection, and appropriate management of AF in patients with CIED should be emphasized.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E, et al. Trends in permanent pacemaker implantation in the United States from 1993 to 2009: increasing complexity of patients and procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:1540–1545. PMID: 22999727.2. Lee JH, Lee SR, Choi EK, et al. Temporal trends of cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: a nationwide population-based study. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:841–852. PMID: 31074230.3. Chao TF, Liu CJ, Tuan TC, et al. Lifetime risks, projected numbers, and adverse outcomes in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the Taiwan Nationwide AF Cohort Study. Chest. 2018; 153:453–466. PMID: 29017957.4. van Rees JB, Borleffs CJ, de Bie MK, et al. Inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks: incidence, predictors, and impact on mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:556–562. PMID: 21272746.5. Santini M, Gasparini M, Landolina M, et al. Device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmias predict adverse outcome in real-world patients with implantable biventricular defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:167–172. PMID: 21211688.6. Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data resource profile: the national health information database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:799–800. PMID: 27794523.7. Lee HJ, Choi EK, Han KD, et al. Bodyweight fluctuation is associated with increased risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2020; 17:365–371. PMID: 31585180.8. Lee SR, Choi EK, Kwon S, et al. Oral anticoagulation in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation and a history of intracranial hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020; 51:416–423. PMID: 31813363.9. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009; 28:3083–3107. PMID: 19757444.10. Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, et al. The relationship between daily atrial tachyarrhythmia burden from implantable device diagnostics and stroke risk: the TRENDS study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009; 2:474–480. PMID: 19843914.11. Kim M, Kim TH, Yu HT, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clinically relevant atrial high-rate episodes in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:235–247. PMID: 33655723.12. Kaplan RM, Koehler J, Ziegler PD, Sarkar S, Zweibel S, Passman RS. Stroke risk as a function of atrial fibrillation duration and CHA2DS2-VASc score. Circulation. 2019; 140:1639–1646. PMID: 31564126.13. Al-Gibbawi M, Ayinde HO, Bhatia NK, et al. Relationship between device-detected burden and duration of atrial fibrillation and risk of ischemic stroke. Heart Rhythm. 2021; 18:338–346. PMID: 33250442.14. Belkin MN, Soria CE, Waldo AL, et al. Incidence and clinical significance of new-onset device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmia: a meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018; 11:e005393. PMID: 29540371.15. Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:120–129. PMID: 22236222.16. Pedersen KB, Madsen C, Sandgaard NC, Diederichsen AC, Bak S, Brandes A. Subclinical atrial fibrillation in patients with recent transient ischemic attack. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2018; 29:707–714. PMID: 29478291.17. Chent XL, Ren XJ, Liang Z, Han ZH, Zhang T, Luo Z. Analyses of risk factors and prognosis for new-onset atrial fibrillation in elderly patients after dual-chamber pacemaker implantation. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018; 15:628–633. PMID: 30416511.18. Wachter R, Freedman B. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2021; 121:697–699. PMID: 34020463.19. Turagam MK, Garg J, Whang W, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170:41–50. PMID: 30583296.20. Johnson JN, Tester DJ, Perry J, Salisbury BA, Reed CR, Ackerman MJ. Prevalence of early-onset atrial fibrillation in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008; 5:704–709. PMID: 18452873.21. Hayashi H, Sumiyoshi M, Nakazato Y, Daida H. Brugada syndrome and sinus node dysfunction. J Arrhythm. 2018; 34:216–221. PMID: 29951135.22. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:373–498. PMID: 32860505.23. Lee SS, Ae Kong K, Kim D, et al. Clinical implication of an impaired fasting glucose and prehypertension related to new onset atrial fibrillation in a healthy Asian population without underlying disease: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:2599–2607. PMID: 28662568.24. Connolly SJ, Kerr CR, Gent M, et al. Effects of physiologic pacing versus ventricular pacing on the risk of stroke and death due to cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1385–1391. PMID: 10805823.25. Pastore G, Zanon F, Baracca E, et al. The risk of atrial fibrillation during right ventricular pacing. Europace. 2016; 18:353–358. PMID: 26443444.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Implication of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in the Individuals With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices

- What Does Atrial Fibrillation Mean in Patients With Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices?

- How and When to Screen for Atrial Fibrillation after Stroke: Insights from Insertable Cardiac Monitoring Devices

- 2021 Korean Heart Rhythm Society Guidelines for Screening and Management of Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation

- Early Detection of Subclinical Atrial Flutter-Fibrillation in Patients with Unexplained Palpitation Using a Novel VDD Defibrillator with Integrated Atrial-Sensing Rings