Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2024 Jan;28(1):21-30. 10.4196/kjpp.2024.28.1.21.

Inhibition of Wnt/ββ-catenin signaling by monensin in cervical cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Xiangyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, Hubei 441000, China

- KMID: 2550276

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2024.28.1.21

Abstract

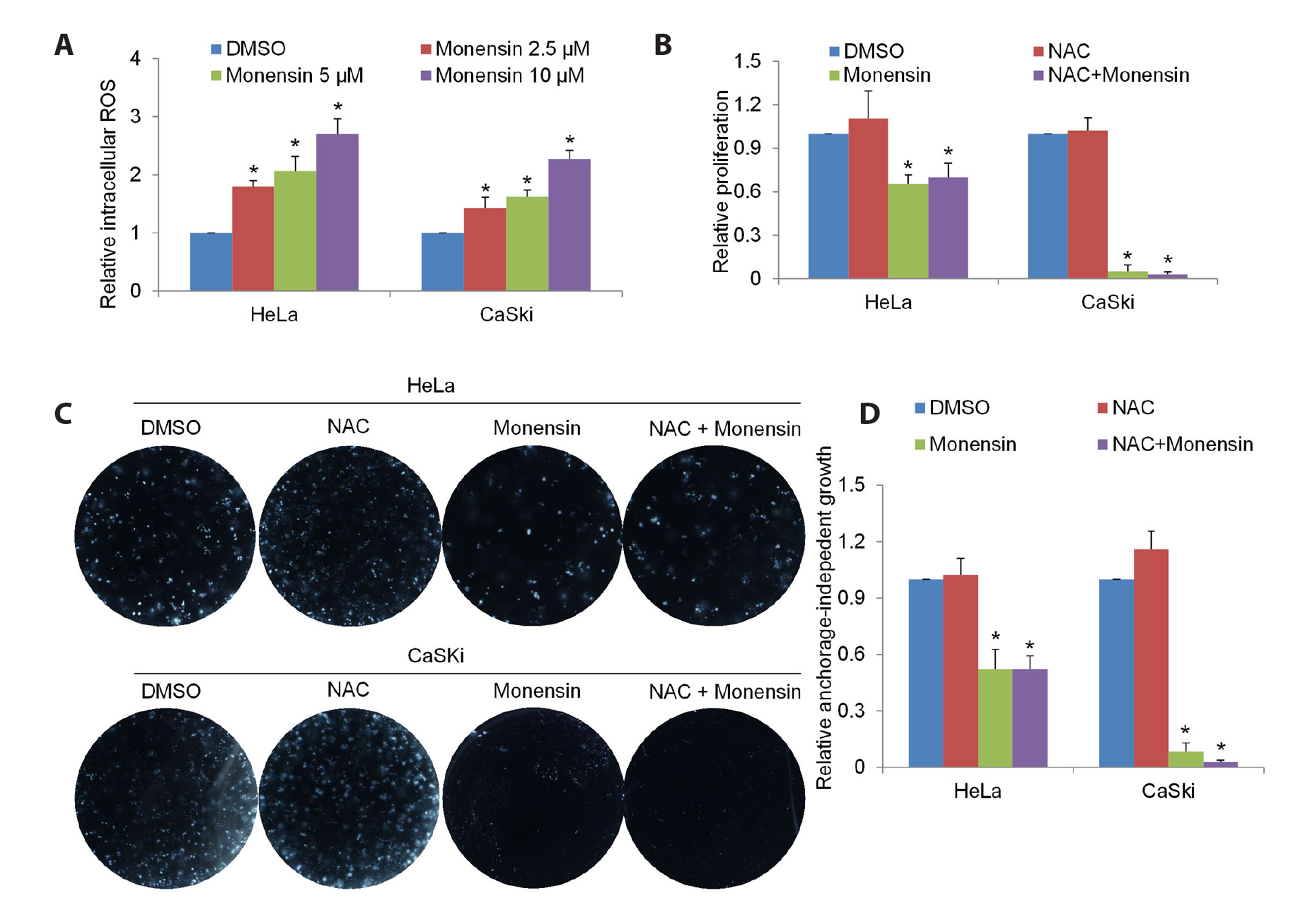

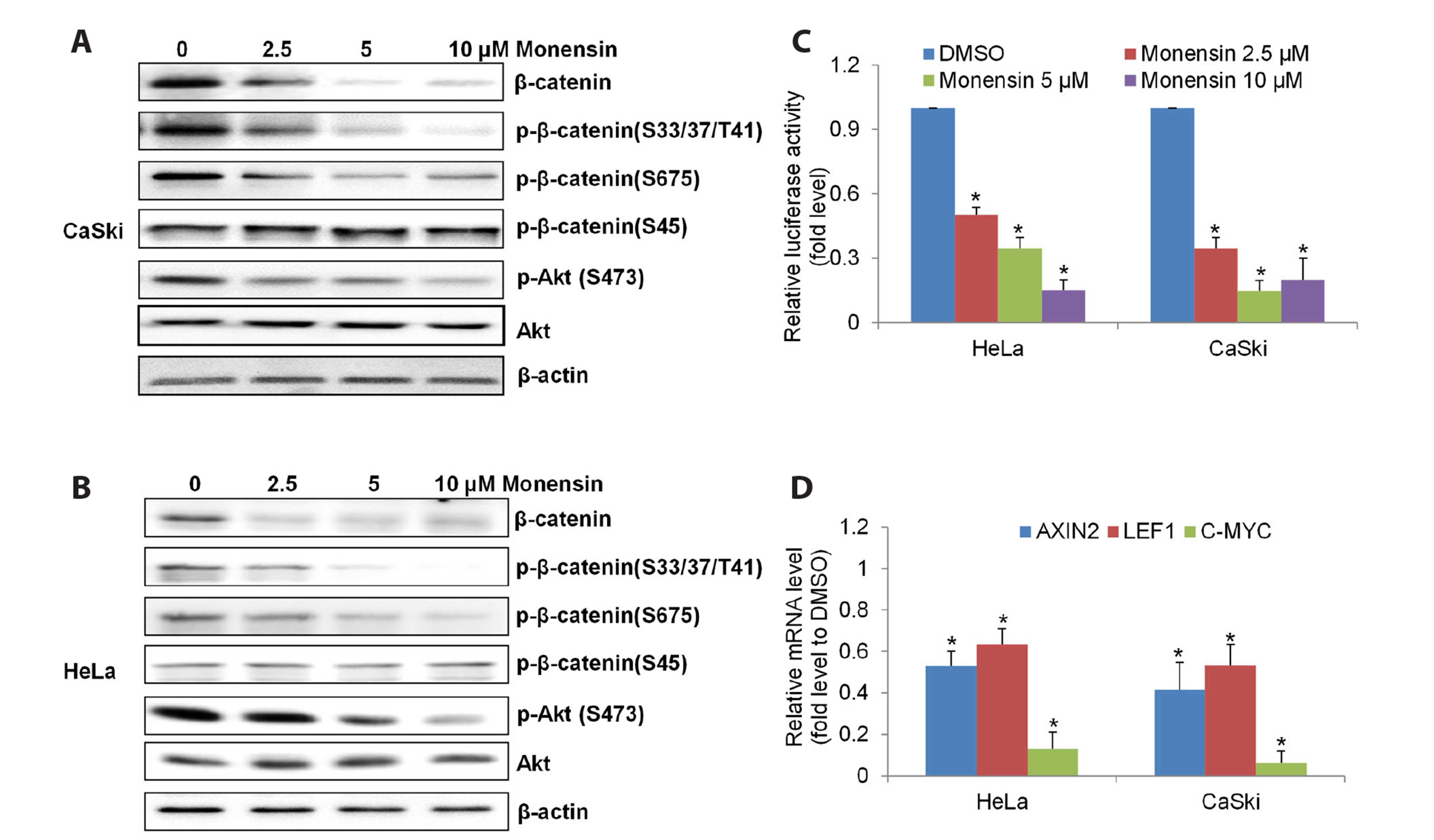

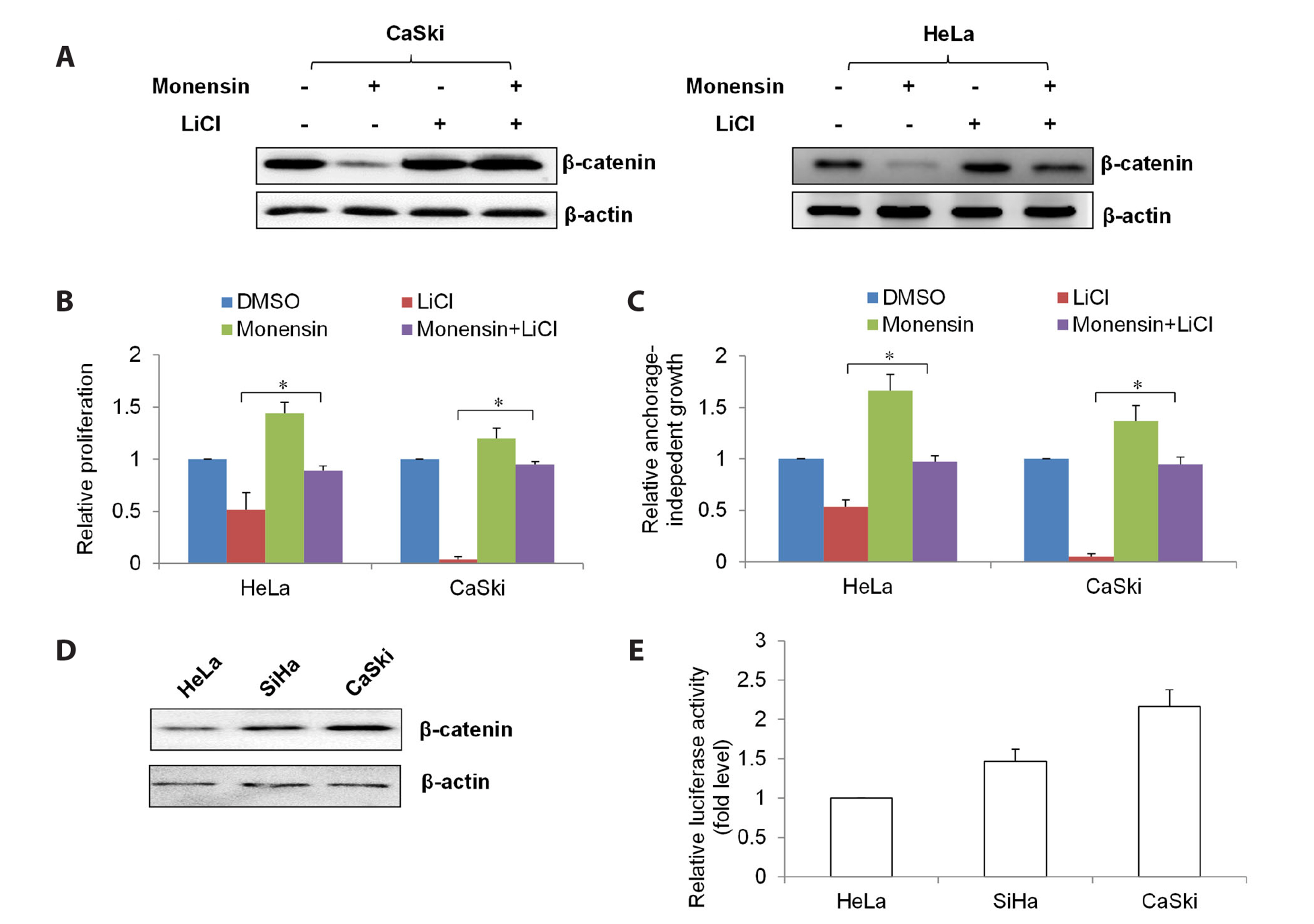

- The challenging clinical outcomes associated with advanced cervical cancer underscore the need for a novel therapeutic approach. Monensin, a polyether antibiotic, has recently emerged as a promising candidate with anti-cancer properties. In line with these ongoing efforts, our study presents compelling evidence of monensin's potent efficacy in cervical cancer. Monensin exerts a pronounced inhibitory impact on proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. Additionally, monensin significantly inhibited cervical cancer growth in vivo without causing any discernible toxicity in mice. Mechanism studies show that monensin's anti-cervical cancer activity can be attributed to its capacity to inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, rather than inducing oxidative stress. Monensin effectively reduces both the levels and activity of β-catenin, and we identify Akt, rather than CK1, as the key player involved in monensin-mediated Wnt/β-catenin inhibition. Rescue studies using Wnt activator and β-catenin-overexpressing cells confirmed that β-catenin inhibition is the mechanism of monensin’s action. As expected, cervical cancer cells exhibiting heightened Wnt/β-catenin activity display increased sensitivity to monensin treatment. In conclusion, our findings provide pre-clinical evidence that supports further exploration of monensin's potential for repurposing in cervical cancer therapy, particularly for patients exhibiting aberrant Wnt/β-catenin activation.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Tewari KS, Sill MW, Penson RT, Huang H, Ramondetta LM, Landrum LM, Oaknin A, Reid TJ, Leitao MM, Michael HE, DiSaia PJ, Copeland LJ, Creasman WT, Stehman FB, Brady MF, Burger RA, Thigpen JT, Birrer MJ, Waggoner SE, Moore DH, et al. 2017; Bevacizumab for advanced cervical cancer: final overall survival and adverse event analysis of a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (Gynecologic Oncology Group 240). Lancet. 390:1654–1663. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31607-0. PMID: 28756902.2. Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. 2019; Cervical cancer. Lancet. 393:169–182. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32470-X. PMID: 30638582.3. Yang M, Wang M, Li X, Xie Y, Xia X, Tian J, Zhang K, Tang A. 2018; Wnt signaling in cervical cancer? J Cancer. 9:1277–1286. DOI: 10.7150/jca.22005. PMID: 29675109. PMCID: PMC5907676.4. McMellen A, Woodruff ER, Corr BR, Bitler BG, Moroney MR. 2020; Wnt signaling in gynecologic malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 21:4272. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21124272. PMID: 32560059. PMCID: PMC7348953. PMID: 2208e60b068a4396b9afc3f7e3bc0d37.5. Nachliel E, Finkelstein Y, Gutman M. 1996; The mechanism of monensin-mediated cation exchange based on real time measurements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1285:131–145. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-2736(96)00149-6. PMID: 8972697.6. Tyagi M, Patro BS. 2019; Salinomycin reduces growth, proliferation and metastasis of cisplatin resistant breast cancer cells via NF-kB deregulation. Toxicol In Vitro. 60:125–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.05.004. PMID: 31077746.7. Gruber M, Handle F, Culig Z. 2020; The stem cell inhibitor salinomycin decreases colony formation potential and tumor-initiating population in docetaxel-sensitive and docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 80:267–273. DOI: 10.1002/pros.23940. PMID: 31834633. PMCID: PMC7003856.8. Klose J, Trefz S, Wagner T, Steffen L, Preißendörfer Charrier A, Radhakrishnan P, Volz C, Schmidt T, Ulrich A, Dieter SM, Ball C, Glimm H, Schneider M. 2019; Salinomycin: anti-tumor activity in a pre-clinical colorectal cancer model. PLoS One. 14:e0211916. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211916. PMID: 30763370. PMCID: PMC6375586. PMID: 6da81f28fab84725b2e66e216f853ab4.9. Li Y, Sun Q, Chen S, Yu X, Jing H. 2022; Monensin inhibits anaplastic thyroid cancer via disrupting mitochondrial respiration and AMPK/mTOR signaling. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 22:2539–2547. DOI: 10.2174/1871520622666220215123620. PMID: 35168524.10. Yao S, Wang W, Zhou B, Cui X, Yang H, Zhang S. 2021; Monensin suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in ovarian cancer by enhancing MEK1 SUMOylation. Exp Ther Med. 22:1390. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10826. PMID: 34650638. PMCID: PMC8506924.11. Yusenko MV, Trentmann A, Andersson MK, Ghani LA, Jakobs A, Arteaga Paz MF, Mikesch JH, Peter von Kries J, Stenman G, Klempnauer KH. 2020; Monensin, a novel potent MYB inhibitor, suppresses proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia and adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 479:61–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.01.039. PMID: 32014461.12. Xin H, Li J, Zhang H, Li Y, Zeng S, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Deng F. 2019; Monensin may inhibit melanoma by regulating the selection between differentiation and stemness of melanoma stem cells. PeerJ. 7:e7354. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.7354. PMID: 31380151. PMCID: PMC6661142. PMID: 483baa4e0dc543829126e03b568b52e8.13. Sun J, Luo Q, Liu L, Yang X, Zhu S, Song G. 2017; Salinomycin attenuates liver cancer stem cell motility by enhancing cell stiffness and increasing F-actin formation via the FAK-ERK1/2 signalling pathway. Toxicology. 384:1–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.04.006. PMID: 28395993.14. Dayekh K, Johnson-Obaseki S, Corsten M, Villeneuve PJ, Sekhon HS, Weberpals JI, Dimitroulakos J. 2014; Monensin inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking and activation: synergistic cytotoxicity in combination with EGFR inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 13:2559–2571. DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-1086. PMID: 25189541.15. Deng Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Yan Z, Qiao M, Ye J, Wei Q, Wang J, Wang X, Zhao L, Lu S, Tang S, Mohammed MK, Liu H, Fan J, Zhang F, Zou Y, Liao J, Qi H, Haydon RC, et al. 2015; Antibiotic monensin synergizes with EGFR inhibitors and oxaliplatin to suppress the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 5:17523. DOI: 10.1038/srep17523. PMID: 26639992. PMCID: PMC4671000.16. Wang X, Wu X, Zhang Z, Ma C, Wu T, Tang S, Zeng Z, Huang S, Gong C, Yuan C, Zhang L, Feng Y, Huang B, Liu W, Zhang B, Shen Y, Luo W, Wang X, Liu B, Lei Y, et al. 2018; Monensin inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth of chemo-resistant pancreatic cancer cells by targeting the EGFR signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 8:17914. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-36214-5. PMID: 30559409. PMCID: PMC6297164.17. Markowska A, Kaysiewicz J, Markowska J, Huczyński A. 2019; Doxycycline, salinomycin, monensin and ivermectin repositioned as cancer drugs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 29:1549–1554. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.04.045. PMID: 31054863.18. Wan W, Zhang X, Huang C, Chen L, Yang X, Bao K, Peng T. 2020; Monensin inhibits glioblastoma angiogenesis via targeting multiple growth factor receptor signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 530:479–484. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.05.057. PMID: 32595038.19. Ochi K, Suzawa K, Tomida S, Shien K, Takano J, Miyauchi S, Takeda T, Miura A, Araki K, Nakata K, Yamamoto H, Okazaki M, Sugimoto S, Shien T, Yamane M, Azuma K, Okamoto Y, Toyooka S. 2020; Overcoming epithelial-mesenchymal transition-mediated drug resistance with monensin-based combined therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 529:760–765. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.077. PMID: 32736704.20. Gu J, Huang L, Zhang Y. 2020; Monensin inhibits proliferation, migration, and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells via downregulating UBA2. Drug Dev Res. 81:745–753. DOI: 10.1002/ddr.21683. PMID: 32462716.21. Tumova L, Pombinho AR, Vojtechova M, Stancikova J, Gradl D, Krausova M, Sloncova E, Horazna M, Kriz V, Machonova O, Jindrich J, Zdrahal Z, Bartunek P, Korinek V. 2014; Monensin inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 13:812–822. DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0625. PMID: 24552772.22. Isani MA, Gee K, Schall K, Schlieve CR, Fode A, Fowler KL, Grikscheit TC. 2019; Wnt signaling inhibition by monensin results in a period of Hippo pathway activation during intestinal adaptation in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 316:G679–G691. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00343.2018. PMID: 30896968.23. Kapoor A, He R, Venkatadri R, Forman M, Arav-Boger R. 2013; Wnt modulating agents inhibit human cytomegalovirus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 57:2761–2767. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00029-13. PMID: 23571549. PMCID: PMC3716142.24. Guo Y, Hu B, Fu B, Zhu H. 2021; Atovaquone at clinically relevant concentration overcomes chemoresistance in ovarian cancer via inhibiting mitochondrial respiration. Pathol Res Pract. 224:153529. DOI: 10.1016/j.prp.2021.153529. PMID: 34174549.25. Xu Y, Liao S, Wang L, Wang Y, Wei W, Su K, Tu Y, Zhu S. 2021; Galeterone sensitizes breast cancer to chemotherapy via targeting MNK/eIF4E and β-catenin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 87:85–93. DOI: 10.1007/s00280-020-04195-w. PMID: 33159561.26. Pappa KI, Kontostathi G, Makridakis M, Lygirou V, Zoidakis J, Daskalakis G, Anagnou NP. 2017; High resolution proteomic analysis of the cervical cancer cell lines secretome documents deregulation of multiple proteases. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 14:507–521. DOI: 10.21873/cgp.20060. PMID: 29109100. PMCID: PMC6070321.27. Gao CF, Xie Q, Su YL, Koeman J, Khoo SK, Gustafson M, Knudsen BS, Hay R, Shinomiya N, Vande Woude GF. 2005; Proliferation and invasion: plasticity in tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102:10528–10533. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0504367102. PMID: 16024725. PMCID: PMC1180792.28. Kim SH, Kim KY, Yu SN, Park SG, Yu HS, Seo YK, Ahn SC. 2016; Monensin induces PC-3 prostate cancer cell apoptosis via ROS production and Ca2+ homeostasis disruption. Anticancer Res. 36:5835–5843. DOI: 10.21873/anticanres.11168. PMID: 27793906.29. Ketola K, Vainio P, Fey V, Kallioniemi O, Iljin K. 2010; Monensin is a potent inducer of oxidative stress and inhibitor of androgen signaling leading to apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 9:3175–3185. DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0368. PMID: 21159605.30. Taurin S, Sandbo N, Qin Y, Browning D, Dulin NO. 2006; Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 281:9971–9976. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M508778200. PMID: 16476742.31. Xia MY, Zhao XY, Huang QL, Sun HY, Sun C, Yuan J, He C, Sun Y, Huang X, Kong W, Kong WJ. 2017; Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by lithium chloride attenuates d-galactose-induced neurodegeneration in the auditory cortex of a rat model of aging. FEBS Open Bio. 7:759–776. DOI: 10.1002/2211-5463.12220. PMID: 28593132. PMCID: PMC5458451.32. Huczyński A, Ratajczak-Sitarz M, Stefańska J, Katrusiak A, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. 2011; Reinvestigation of the structure of monensin A phenylurethane sodium salt based on X-ray crystallographic and spectroscopic studies, and its activity against hospital strains of methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis and S. aureus. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 64:249–256. DOI: 10.1038/ja.2010.167. PMID: 21224863.33. Verma SP, Das P. 2018; Monensin induces cell death by autophagy and inhibits matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7) in UOK146 renal cell carcinoma cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 54:736–742. DOI: 10.1007/s11626-018-0298-7. PMID: 30324243.34. Pádua D, Barros R, Amaral AL, Mesquita P, Freire AF, Sousa M, Maia AF, Caiado I, Fernandes H, Pombinho A, Pereira CF, Almeida R. 2020; A SOX2 reporter system identifies gastric cancer stem-like cells sensitive to monensin. Cancers (Basel). 12:495. DOI: 10.3390/cancers12020495. PMID: 32093282. PMCID: PMC7072720. PMID: b8683dbda0674f338fd27f3200bd2552.35. Yoon MJ, Kang YJ, Kim IY, Kim EH, Lee JA, Lim JH, Kwon TK, Choi KS. 2013; Monensin, a polyether ionophore antibiotic, overcomes TRAIL resistance in glioma cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress, DR5 upregulation and c-FLIP downregulation. Carcinogenesis. 34:1918–1928. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/bgt137. PMID: 23615398.36. Klose J, Eissele J, Volz C, Schmitt S, Ritter A, Ying S, Schmidt T, Heger U, Schneider M, Ulrich A. 2016; Salinomycin inhibits metastatic colorectal cancer growth and interferes with Wnt/β-catenin signaling in CD133+ human colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 16:896. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-016-2879-8. PMID: 27855654. PMCID: PMC5114842.37. Liu Q, Sun J, Luo Q, Ju Y, Song G. 2021; Salinomycin suppresses tumorigenicity of liver cancer stem cells and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 16:630–637. DOI: 10.2174/1574888X15666200123121225. PMID: 31971116.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Natural Products Targeting Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway

- Inhibition of Wnt Signaling by Silymarin in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells

- Circular RNAs Regulate Cancer Onset and Progression via Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

- Suppression of β-catenin Signaling Pathway in Human Prostate Cancer PC3 Cells by Delphinidin

- Anti-Proliferative Activity of Nodosin, a Diterpenoid from Isodon serra, via Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathways in Human Colon Cancer Cells