Clin Endosc.

2023 Sep;56(5):594-603. 10.5946/ce.2022.182.

Necessity of pharyngeal anesthesia during transoral gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized clinical trial

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan

- 2Innovative Clinical Research Center, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan

- KMID: 2546138

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.182

Abstract

- Background/Aims

The necessity for pharyngeal anesthesia during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is controversial. This study aimed to compare the observation ability with and without pharyngeal anesthesia under midazolam sedation.

Methods

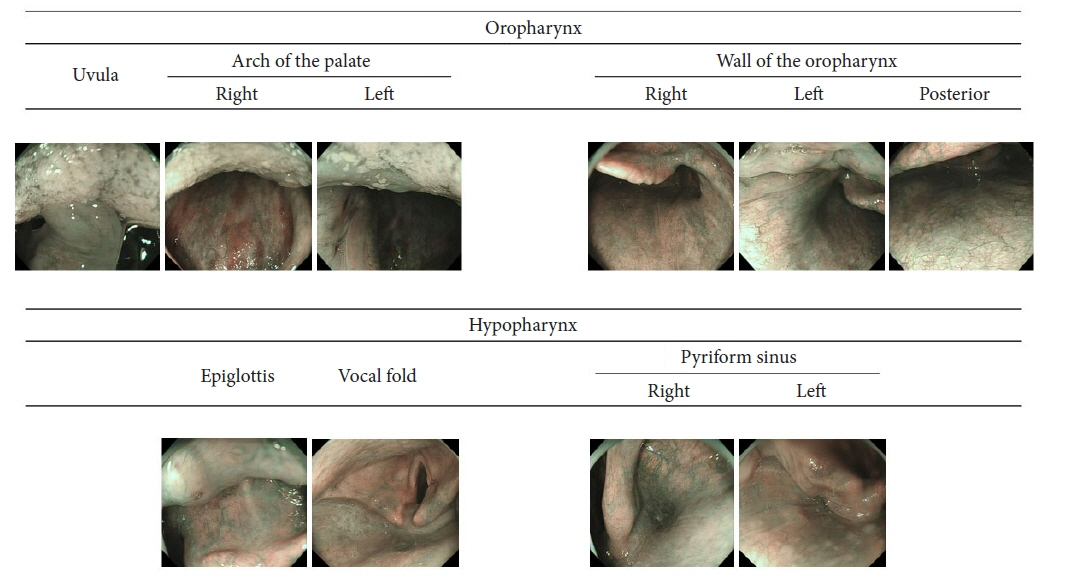

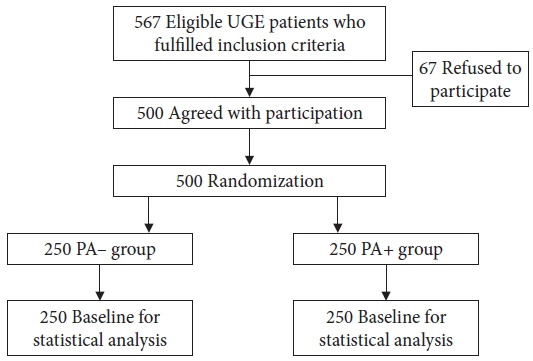

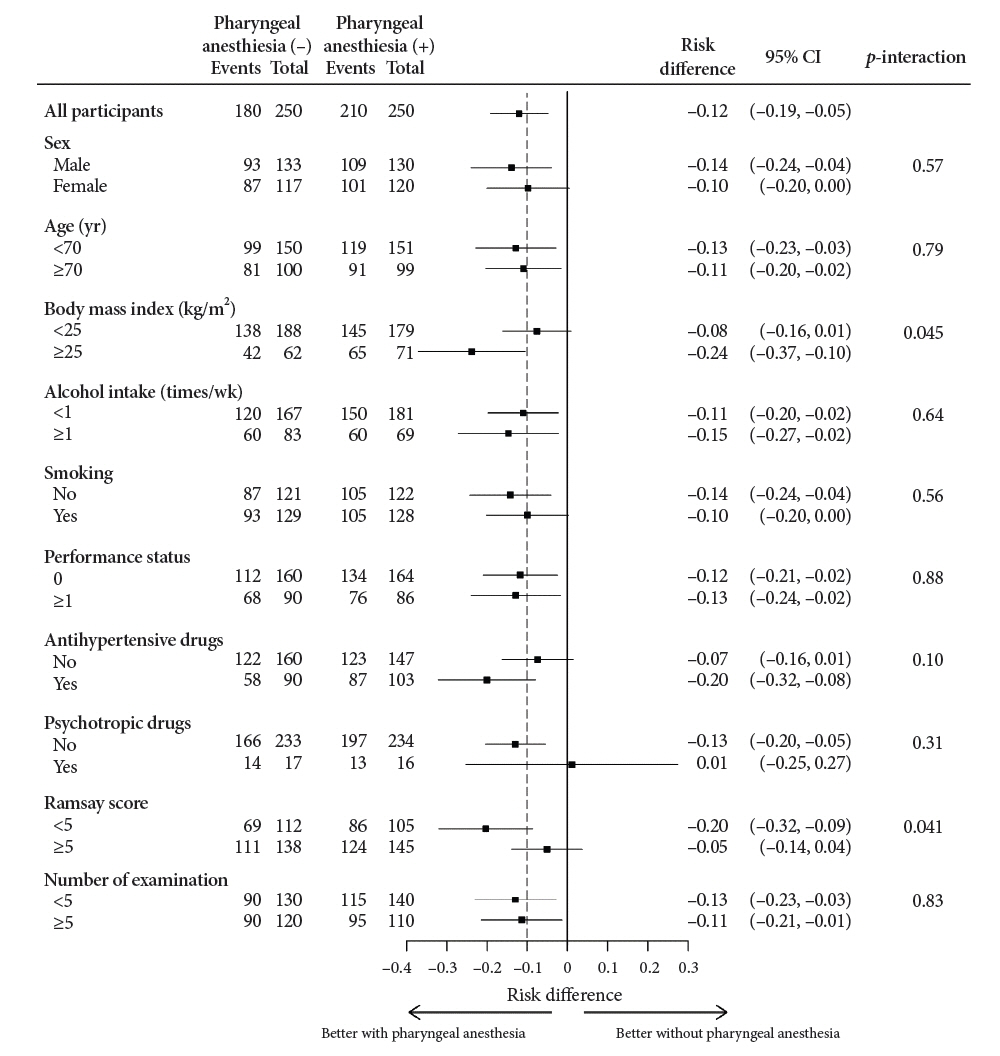

This prospective, single-blinded, randomized study included 500 patients who underwent transoral upper gastrointestinal endoscopy under intravenous midazolam sedation. Patients were randomly allocated to pharyngeal anesthesia: PA+ or PA– groups (250 patients/group). The endoscopists obtained 10 images of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. The primary outcome was the non-inferiority of the PA– group in terms of the pharyngeal observation success rate.

Results

The pharyngeal observation success rates in the pharyngeal anesthesia with and without (PA+ and PA–) groups were 84.0% and 72.0%, respectively. The PA– group was inferior (p=0.707, non-inferiority) to the PA+ group in terms of observable parts (8.33 vs. 8.86, p=0.006), time (67.2 vs. 58.2 seconds, p=0.001), and pain (1.21±2.37 vs. 0.68±1.78, p=0.004, 0–10 point visual analog scale). Suitable quality images of the posterior wall of the oropharynx, vocal fold, and pyriform sinus were inferior in the PA– group. Subgroup analysis showed a higher sedation level (Ramsay score ≥5) with almost no differences in the pharyngeal observation success rate between the groups.

Conclusions

Non-pharyngeal anesthesia showed no non-inferiority in pharyngeal observation ability. Pharyngeal anesthesia may improve pharyngeal observation ability in the hypopharynx and reduce pain. However, deeper anesthesia may reduce this difference.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Leslie K, Stonell CA. Anaesthesia and sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2005; 18:431–436.2. Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, et al. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999; 11:201–204.3. Mogensen S, Treldal C, Feldager E, et al. New lidocaine lozenge as topical anesthesia compared to lidocaine viscous oral solution before upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Local Reg Anesth. 2012; 5:17–22.4. Shaoul R, Higaze H, Lavy A. Evaluation of topical pharyngeal anaesthesia by benzocaine lozenge for upper endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006; 24:687–694.5. Evans LT, Saberi S, Kim HM, et al. Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: is "the spray" beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:761–766.6. Hwang SH, Park CS, Kim BG, et al. Topical anesthetic preparations for rigid and flexible endoscopy: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015; 272:263–270.7. Watanabe J, Ikegami Y, Tsuda A, et al. Lidocaine spray versus viscous lidocaine solution for pharyngeal local anesthesia in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Endosc. 2021; 33:538–548.8. Furuta T, Kato M, Ito T, et al. 6th report of endoscopic complications: results of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society Survey from 2008 to 2012. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2016; 58:1466–1491.9. Obara K, Haruma K, Irisawa A, et al. Guidelines for sedation in gastroenterological endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2015; 27:435–449.10. Bahar E, Yoon H. Lidocaine: a local anesthetic, its adverse effects and management. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021; 57:782.11. Jeong J, Jung K, Seo KI, et al. Propofol alone prevents worsening hepatic encephalopathy rather than midazolam alone or combined sedation after esophagogastroduodenoscopy in compensated or decompensated cirrhotic patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 32:1054–1061.12. Kim DB, Kim JS, Huh CW, et al. Propofol compared with bolus and titrated midazolam for sedation in outpatient colonoscopy: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021; 93:201–208.13. de la Morena F, Santander C, Esteban C, et al. Usefulness of applying lidocaine in esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed under sedation with propofol. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 5:231–239.14. Sun X, Xu Y, Zhang X, et al. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia provides no additional benefit to propofol sedation for esophagogastroduodenoscopy: a randomized controlled double-blinded clinical trial. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:6682.15. Muto M, Nakane M, Katada C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ at oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal mucosal sites. Cancer. 2004; 101:1375–1381.16. Muto M, Katada C, Sano Y, et al. Narrow band imaging: a new diagnostic approach to visualize angiogenesis in superficial neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005; 3(7 Suppl 1):S16–20.17. Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T, et al. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:1566–1572.18. Tsuji K, Doyama H, Takeda Y, et al. Use of transoral endoscopy for pharyngeal examination: cross-sectional analysis. Dig Endosc. 2014; 26:344–349.19. Hayashi T, Asahina Y, Waseda Y, et al. Lidocaine spray alone is similar to spray plus viscous solution for pharyngeal observation during transoral endoscopy: a clinical randomized trial. Endosc Int Open. 2017; 5:E47–E53.20. Hayashi T, Kitamura K, Kaneko S, et al. Comparison of still and moving image of pharyngeal observation in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2021; 63:901.21. Collinsworth KA, Kalman SM, Harrison DC. The clinical pharmacology of lidocaine as an antiarrhythymic drug. Circulation. 1974; 50:1217–1230.22. Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, et al. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974; 2:656–659.23. Chow SC, Shao J, Wang H, et al. Sample size calculations in clinical research. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press;2017.24. Sami SS, Subramanian V, Ortiz-Fernández-Sordo J, et al. Performance characteristics of unsedated ultrathin video endoscopy in the assessment of the upper GI tract: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 82:782–792.25. Parker C, Alexandridis E, Plevris J, et al. Transnasal endoscopy: no gagging no panic! Frontline Gastroenterol. 2016; 7:246–256.26. Phillips F, Crowley J, Warburton S, et al. Aerosol and droplet generation in upper and lower GI endoscopy: whole procedure and event-based analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022; 96:603–611.27. Draper MR, Blagnys B, Premachandra DJ. To "EE" or not to "EE". J Otolaryngol. 2007; 36:191–195.28. Mori S, Yokoyama A, Matsui T, et al. Endoscopic screening for upper aerodigestive tract cancer in alcoholics using wide visualization of the pharynx and esophageal iodine staining procedures. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2011; 53:1426–1434.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Efficacy of endoscopy under general anesthesia for the detection of synchronous lesions in oro-hypopharyngeal cancer

- Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy without Topical Pharyngeal Anesthesia

- Transoral Videolaryngoscopic Surgery for Pharyngeal Stenosis: Two Case Studies

- Lidocaine spray on an endoscope immediately before insertion improves patient tolerance to endoscopy: A single center, clinical observational study

- Nasopharyngeal examination during transoral upper gastrointestinal endoscopy