J Neurocrit Care.

2023 Jun;16(1):46-50. 10.18700/jnc.230019.

Unexpected epileptogenic effect of lethal doses of pentobarbital: a case report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Intensive Care Unit, Department of Intensive Care, University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- 2Forensic Toxicology and Chemistry Unit, University Centre of Legal Medicine Lausanne-Geneva, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 3Geneva University Hospital and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- 4EEG and Epilepsy Unit, Neurology Unit, Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Faculty of Medicine of Geneva, University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- KMID: 2543393

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.18700/jnc.230019

Abstract

- Background

Barbiturate poisoning is rare but potentially fatal.

Case Report

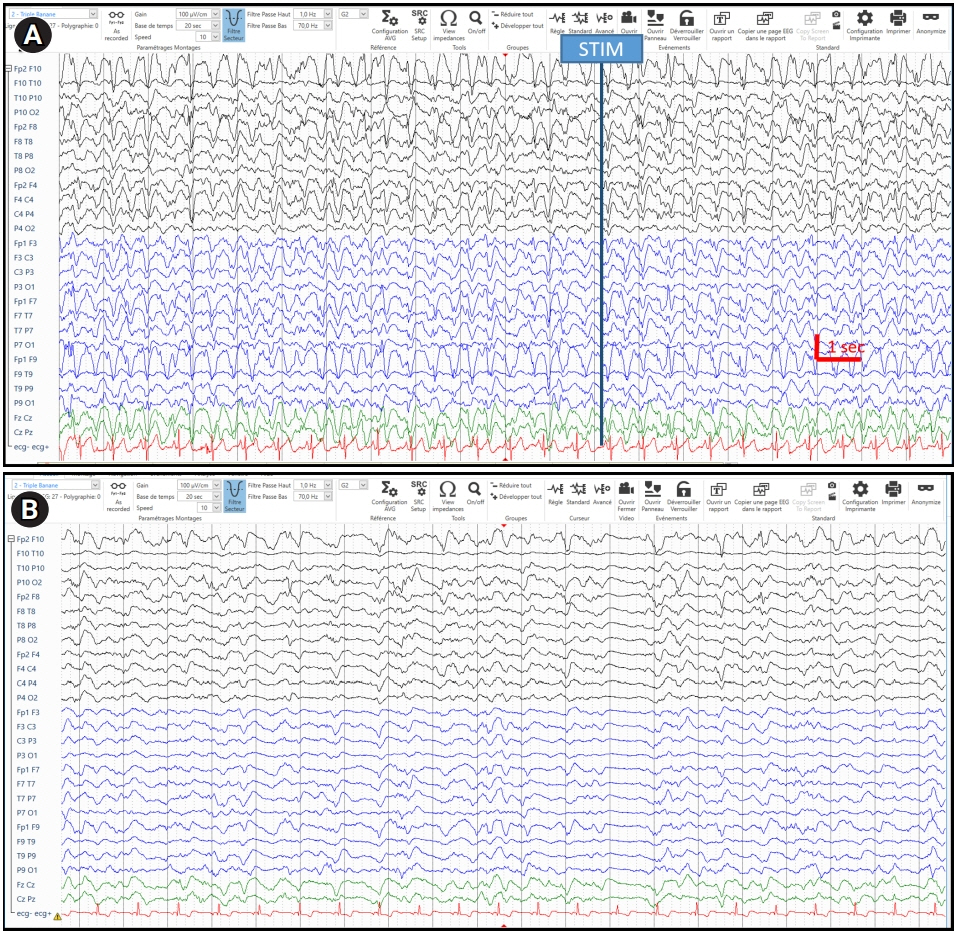

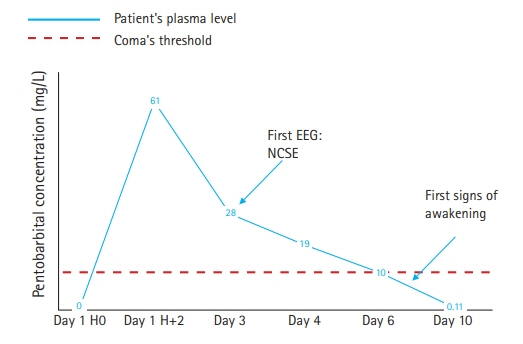

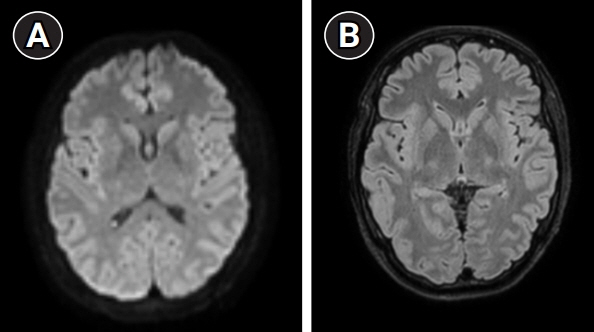

We reported a case of barbiturate poisoning in a 28-year-old woman who recovered from lethal pentobarbital deliberate self-poisoning. The initial blood pentobarbital concentration was 61 mg/L, corresponding to a potentially lethal dose. Despite the ingestion of a high dose of pentobarbital, the electroencephalogram revealed an unattended pattern compatible with possible nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Following resuscitation maneuvers, appropriate care, and antiseizure medication, the patient awakened after 7 days. The evolution was excellent without neurological deficits at 2 months.

Conclusion

Despite the expected and known effects of high-dose pentobarbital in reducing and suppressing cortical activity in the brain, the present case demonstrates that lethal dose of pentobarbital may have an epileptogenic effect. Our hypothesis was that the mechanism of the origin of such a picture is a relatively abrupt decrease in toxic doses of pentobarbital, resulting in a withdrawal phenomenon.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Löscher W, Rogawski MA. How theories evolved concerning the mechanism of action of barbiturates. Epilepsia. 2012; 53 Suppl 8:12–25.2. Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, Alldredge B, Bleck TP, Glauser T, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012; 17:3–23.3. Giroud C, Augsburger M, Horisberger B, Lucchini P, Rivier L, Mangin P. Exit association-mediated suicide: toxicologic and forensic aspects. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999; 20:40–4.4. Druda DF, Gone S, Graudins A. Deliberate self-poisoning with a lethal dose of entobarbital with confirmatory serum drug concentrations: survival after cardiac arrest with supportive care. J Med Toxicol. 2019; 15:45–8.5. Winek CL, Wahba WW, Winek CL Jr, Balzer TW. Drug and chemical blood-level data 2001. Forensic Sci Int. 2001; 122:107–23.6. Hirsch LJ, Fong MW, Leitinger M, LaRoche SM, Beniczky S, Abend NS, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society's standardized critical care EEG terminology: 2021 version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2021; 38:1–29.7. Leitinger M, Beniczky S, Rohracher A, Gardella E, Kalss G, Qerama E, et al. Salzburg consensus criteria for non-convulsive status epilepticus—approach to clinical application. Epilepsy Behav. 2015; 49:158–63.8. Roberts DM, Buckley NA. Enhanced elimination in acute barbiturate poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011; 49:2–12.9. Mactier R, Laliberté M, Mardini J, Ghannoum M, Lavergne V, Gosselin S, et al. Extracorporeal treatment for barbiturate poisoning: recommendations from the EXTRIP Workgroup. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014; 64:347–58.10. Krishnamurthy KB, Drislane FW. Depth of EEG suppression and outcome in barbiturate anesthetic treatment for refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:759–62.11. Rossetti AO, Logroscino G, Liaudet L, Ruffieux C, Ribordy V, Schaller MD, et al. Status epilepticus: an independent outcome predictor after cerebral anoxia. Neurology. 2007; 69:255–60.12. Mauritz M, Hirsch LJ, Camfield P, Chin R, Nardone R, Lattanzi S, et al. Acute symptomatic seizures: an educational, evidence-based review. Epileptic Disord. 2022; 24:26–49.13. Iivanainen M, Savolainen H. Side effects of phenobarbital and phenytoin during long-term treatment of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1983; 97:49–67.14. Silva-Barrat C, Champagnat J, Menini C. The GABA-withdrawal syndrome: a model of local status epilepticus. Neural Plast. 2000; 7:9–18.15. Bhatt AB, Popescu A, Waterhouse EJ, Abou-Khalil BW. De novo generalized periodic discharges related to anesthetic withdrawal resolve spontaneously. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2014; 31:194–8.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of Pentobarbital on Experimental Brain Edema in Rabbit

- Does Enflurane or Isoflurane Augment Mivacurium-induced Neuromuscular Block with Preceded Succinylcholine in the Cat?

- Induction with Intravenous 0.3 mg/kg Etomidate Maintains Venous Capacitance of Normovolemic Rat

- Effects of Barburic Anestheties on Renal Function in Rabbits

- A Long - term Effect of Pentobarbital on the Atrial Natriuretic Peptide System in Rats