Korean J Transplant.

2023 Mar;37(1):29-40. 10.4285/kjt.22.0049.

Changes in socioeconomic status and patient outcomes in kidney transplantation recipients in South Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Biomedical Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Biostatistics, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Kidney Research Institute, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2541310

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/kjt.22.0049

Abstract

- Background

Socioeconomic status is an important factor affecting the accessibility and prognosis of kidney transplantation. We aimed to investigate changes in kidney transplant recipients’ socioeconomic status in South Korea and whether such changes were associated with patient prognosis.

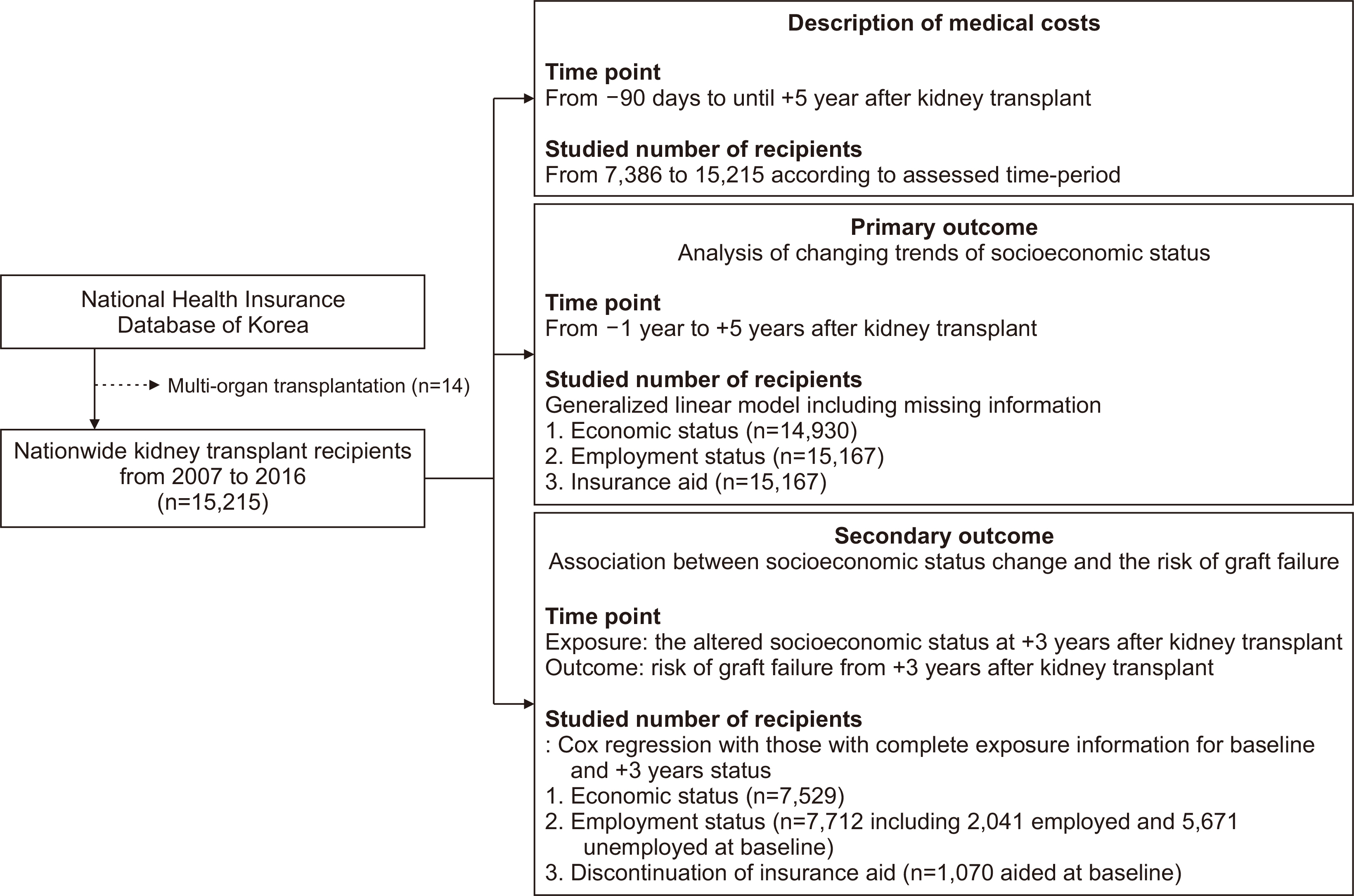

Methods

This retrospective nationwide o bservational c ohort s tudy i n S outh Korea included kidney transplant recipients between 2007 and 2016. South Korea provides a single-insurer health insurance service, and information on the socioeconomic status of the recipients is identifiable through the claims database. First, a generalized linear mixed model was used to investigate changes in recipients’ socioeconomic status as an outcome. Second, the risk of graft failure was analyzed using Cox regression as another outcome to investigate whether changes in socioeconomic status were associated with patient prognosis.

Results

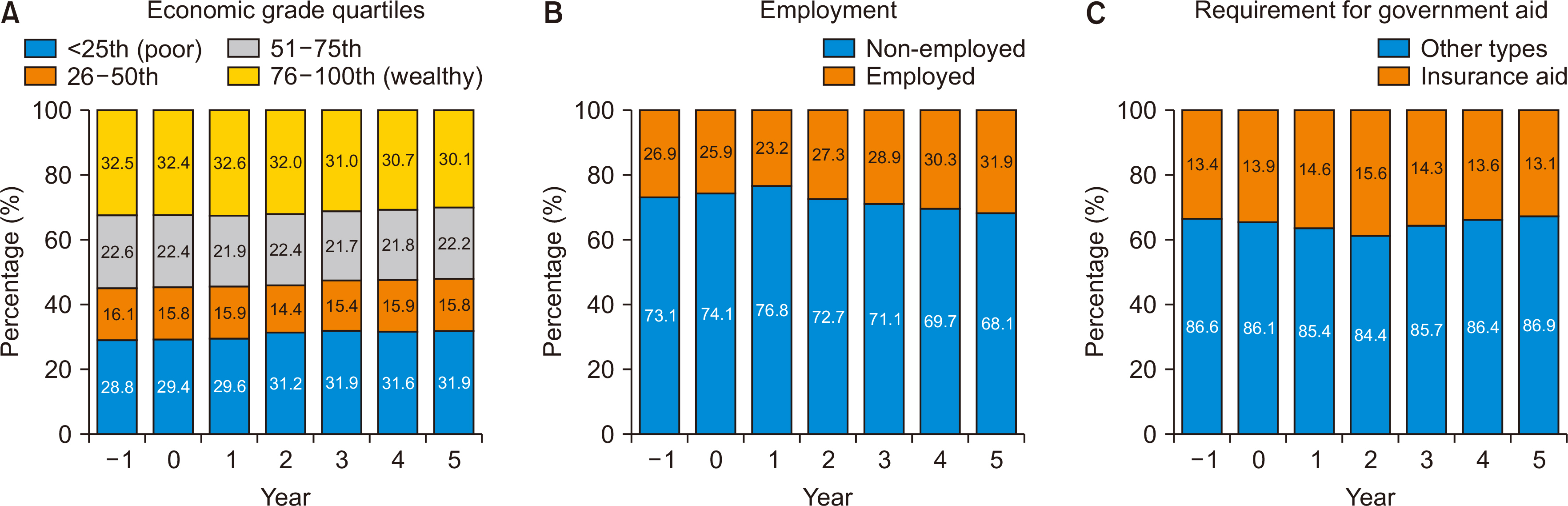

Among the 15,215 kidney transplant recipients included in the study, economic levels (defined based on insurance fee percentiles) and employment rates declined within the first 2 years after transplantation. Beyond 2 years, the employment rate increased significantly, while no significant changes were observed in economic status. Patients whose economic status did not improve 3 years after kidney transplantation showed a higher risk of death than those whose status improved. When compared to those who remained employed after kidney transplantation, unemployment was associated with a significantly higher risk of death-censored graft failure.

Conclusions

The socioeconomic status of kidney transplant recipients changed dynamically after kidney transplantation, and these changes were associated with patient prognosis.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al. 1999; Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 341:1725–30. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. PMID: 10580071.2. Gordon EJ, Butt Z, Jensen SE, Lok-Ming Lehr A, Franklin J, Becker Y, et al. 2013; Opportunities for shared decision making in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 13:1149–58. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.12195. PMID: 23489435.3. Park S, Park GC, Park J, Kim JE, Yu MY, Kim K, et al. 2021; Disparity in accessibility to and prognosis of kidney transplantation according to economic inequality in South Korea: a widening gap after expansion of insurance coverage. Transplantation. 105:404–12. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003256. PMID: 32265414.4. Park S, Park J, Kim M, Kim JE, Yu MY, Kim K, et al. 2021; Socioeconomic dependency and kidney transplantation accessibility and outcomes: a nationwide observational cohort study in South Korea. J Nephrol. 34:211–9. DOI: 10.1007/s40620-020-00876-0. PMID: 33048288.5. Roodnat JI, Laging M, Massey EK, Kho M, Kal-van Gestel JA, Ijzermans JN, et al. 2012; Accumulation of unfavorable clinical and socioeconomic factors precludes living donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 93:518–23. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318243030f. PMID: 22298031.6. Kasiske BL, London W, Ellison MD. 1998; Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. J Am Soc Nephrol. 9:2142–7. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.V9112142. PMID: 9808103.7. Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Koford JK, Baird BC, Chelamcharla M, Habib AN, Wang BJ, et al. 2006; Role of socioeconomic status in kidney transplant outcome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 1:313–22. DOI: 10.2215/CJN.00630805. PMID: 17699222.8. Begaj I, Khosla S, Ray D, Sharif A. 2013; Socioeconomic deprivation is independently associated with mortality post kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 84:803–9. DOI: 10.1038/ki.2013.176. PMID: 23715126.9. Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR, Segev DL, Gentry SE, et al. 2010; The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 5:2276–88. DOI: 10.2215/CJN.04940610. PMID: 20798250. PMCID: PMC2994090.10. D'Egidio V, Mannocci A, Ciaccio D, Sestili C, Cocchiara RA, Del Cimmuto A, et al. 2019; Return to work after kidney transplant: a systematic review. Occup Med (Lond). 69:412–8. DOI: 10.1093/occmed/kqz095. PMID: 31394573.11. Messias AA, Reichelt AJ, Dos Santos EF, Albuquerque GC, Kramer JS, Hirakata VN, et al. 2014; Return to work after renal transplantation: a study of the Brazilian Public Social Security System. Transplantation. 98:1199–204. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000418. PMID: 25222011.12. De Baere C, Delva D, Kloeck A, Remans K, Vanrenterghem Y, Verleden G, et al. 2010; Return to work and social participation: does type of organ transplantation matter? Transplantation. 89:1009–15. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ce77e5. PMID: 20147883.13. Kirkeskov L, Carlsen RK, Lund T, Buus NH. 2021; Employment of patients with kidney failure treated with dialysis or kidney transplantation-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 22:348. DOI: 10.1186/s12882-021-02552-2. PMID: 34686138. PMCID: PMC8532382.14. Tzvetanov I, D'Amico G, Walczak D, Jeon H, Garcia-Roca R, Oberholzer J, et al. 2014; High rate of unemployment after kidney transplantation: analysis of the United network for organ sharing database. Transplant Proc. 46:1290–4. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.02.006. PMID: 24836836.15. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park JH, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. 2017; Data resource profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 46:799–800.16. Jeon HJ, Bae HJ, Ham YR, Choi DE, Na KR, Ahn MS, et al. 2019; Outcomes of end-stage renal disease patients on the waiting list for deceased donor kidney transplantation: a single-center study. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 38:116–23. DOI: 10.23876/j.krcp.18.0068. PMID: 30743320. PMCID: PMC6481973.17. Kutner NG, Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Amaral S. 2012; Perspectives on the new kidney disease education benefit: early awareness, race and kidney transplant access in a USRDS study. Am J Transplant. 12:1017–23. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03898.x. PMID: 22226386. PMCID: PMC5844184.18. Keith D, Ashby VB, Port FK, Leichtman AB. 2008; Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 3:463–70. DOI: 10.2215/CJN.02220507. PMID: 18199847. PMCID: PMC2390941.19. Zhang Y, Gerdtham UG, Rydell H, Jarl J. 2018; Socioeconomic inequalities in the kidney transplantation process: a registry-based study in Sweden. Transplant Direct. 4:e346. DOI: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000764. PMID: 29464207. PMCID: PMC5811275.20. Park S, Park J, Kang E, Lee JW, Kim Y, Park M, et al. 2022; Economic impact of donating a kidney on living donors: a Korean cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 79:175–84. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.07.009. PMID: 34419516.21. Sharma AK, Gupta R, Tolani SL, Rathi GL, Gupta HP. 2000; Evaluation of socioeconomic factors in noncompliance in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 32:1864. DOI: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)01467-6. PMID: 11119974.22. Merzkani MA, Bentall AJ, Smith BH, Benavides Lopez X, D'Costa MR, Park WD, et al. 2022; Death with function and graft failure after kidney transplantation: risk factors at baseline suggest new approaches to management. Transplant Direct. 8:e1273. DOI: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001273. PMID: 35047660. PMCID: PMC8759617.

Article23. Mayrdorfer M, Liefeldt L, Osmanodja B, Naik MG, Schmidt D, Duettmann W, et al. 2022; A single center in-depth analysis of death with a functioning kidney graft and reasons for overall graft failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. gfac327. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfac327. PMID: 36477607.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Transfusion status in liver and kidney transplantation recipients: results from nationwide claims database

- The effect of a recipient’s body mass index to kidney transplantation outcomes: a retrospective cohort study at National Kidney and Transplant Institute

- Hypertension after kidney transplantation

- A Concept Analysis of Compliance in Kidney Transplant Recipient Including Compliance with Immunosuppressive Medication

- The Effectiveness of Perceived Stress and Social Support on the Quality of Life for Kidney Transplantation Recipients