J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Mar;38(10):e74. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e74.

Prevalence and Related Factors of Depression Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings From the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Instituite of Public Health and Medical Care, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3International Healthcare Center, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2540432

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e74

Abstract

- Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has greatly altered the daily lives of people in unprecedented ways, causing a variety of mental health problems. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the prevalence of depression among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and explore the factors associated with depressive mood using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey (KNHANES).

Methods

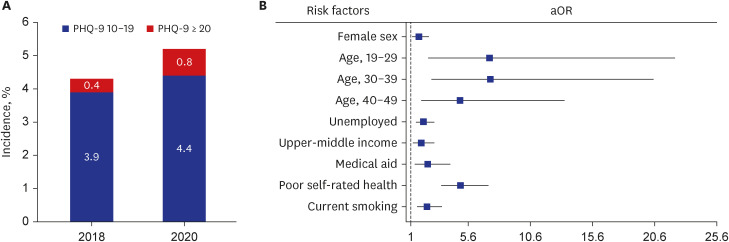

We analyzed participants aged ≥ 19 years from KNHANES 2018 (n = 5,837) and 2020 (n = 5,265) to measure and compare the prevalence of depression before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression was defined as a score ≥ 10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Furthermore, we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to investigate the independent predictors of depressive mood during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

The prevalence of depression was notably higher during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the pre-pandemic period (5.2% vs. 4.3%, P = 0.043). In a multivariate model, female sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10-2.41), age < 50 years (19–29 years: aOR, 7.31; 95% CI, 2.40–22.21; 30–39 years: aOR, 7.38; 95% CI, 2.66–20.47; 40–49 years: aOR, 4.94; 95% CI, 1.84–13.31 compared to ≥ 80 years), unemployment (aOR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.41–2.85), upper-middle class household income (aOR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.18– 2.85 compared to upper-class income), being a beneficiary of Medicaid (aOR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.33–4.14), poor self-rated health (aOR, 4.99; 95% CI, 1.51–3.47 compared to good self-rated health), and current smoking (aOR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.51–3.47) were found to be significant risk factors for depression during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Depression was significantly more prevalent among Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic than in the pre-pandemic era. Therefore, more attention should be paid to individuals vulnerable to depression during pandemics. Implementing psychological support public policies and developing interventions to prevent the adverse outcomes of COVID-19-related depression should be considered.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update, Edition 101, 20 July 2022. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2022.2. Zhang Y, Janda KM, Ranjit N, Salvo D, Nielsen A, van den Berg A. Change in depression and its determinants during the covid-19 pandemic: a longitudinal examination among racially/ethnically diverse us adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1194. PMID: 35162214.3. Chung PC, Chan TC. Impact of physical distancing policy on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 globally: perspective from government’s response and residents’ compliance. PLoS One. 2021; 16(8):e0255873. PMID: 34375342.4. Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, Bosse NI, Jarvis CI, Russell TW, et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8(4):e488–e496. PMID: 32119825.5. Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, Unwin HJT, Mellan TA, Coupland H, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020; 584(7820):257–261. PMID: 32512579.6. Berkowitz SA, Basu S. Unemployment insurance, health-related social needs, health care access, and mental health during the covid-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021; 181(5):699–702. PMID: 33252615.7. Bridgland VM, Moeck EK, Green DM, Swain TL, Nayda DM, Matson LA, et al. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS One. 2021; 16(1):e0240146. PMID: 33428630.8. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in us adults before and during the covid-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(9):e2019686. PMID: 32876685.9. Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021; 21(1):100196. PMID: 32904715.10. Khademian F, Delavari S, Koohjani Z, Khademian Z. An investigation of depression, anxiety, and stress and its relating factors during COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1):275. PMID: 33535992.11. Balakrishnan V, Ng KS, Kaur W, Govaichelvan K, Lee ZL. COVID-19 depression and its risk factors in Asia Pacific - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022; 298(Pt B):47–56. PMID: 34801606.12. Kim DM, Bang YR, Kim JH, Park JH. The prevalence of depression, anxiety and associated factors among the general public during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(29):e214. PMID: 34313037.13. Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Abdalla SM, Sampson L, Trinquart L, Castrucci BC, et al. Persistent depressive symptoms during COVID-19: a national, population-representative, longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022; 5:100091. PMID: 34635882.14. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43(1):69–77. PMID: 24585853.15. Kim Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiol Health. 2014; 36:e2014002. PMID: 24839580.16. Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019; 365:l1781. PMID: 30979729.17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID: 11556941.18. Oh SW. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2011; 35(6):561–566. PMID: 22247896.19. Kim ES, Nam HS. Factors related to regional variation in the high-risk drinking rate in Korea: using quantile regression. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021; 54(2):145–152. PMID: 33845535.20. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018; 320(19):2020–2028. PMID: 30418471.21. Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020; 113(8):531–537. PMID: 32569360.22. Choi KW, Jung JH, Kim HH. Political trust, mental health, and the coronavirus pandemic: a cross-national study. Res Aging. 2023; 45(2):133–148. PMID: 35379034.23. Kong X, Kong F, Zheng K, Tang M, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Effect of psychological–behavioral intervention on the depression and anxiety of covid-19 patients. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:586355. PMID: 33329130.24. Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Sasagawa S. Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. J Affect Disord. 2010; 127(1-3):185–190. PMID: 20573404.25. Rosenfield S, Smith D. Gender and mental health: do men and women have different amounts or types of problems. Scheid TL, Brown TN, editors. A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: SOCIAL Contexts, Theories, and Systems. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;2010. p. 256–267.26. COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021; 398(10312):1700–1712. PMID: 34634250.27. Power K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain Sci Pract Policy. 2020; 16(1):67–73.28. Wenham C, Smith J, Davies SE, Feng H, Grépin KA, Harman S, et al. Women are most affected by pandemics - lessons from past outbreaks. Nature. 2020; 583(7815):194–198. PMID: 32641809.29. Burki T. The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 20(8):904–905. PMID: 32738239.30. Varma P, Junge M, Meaklim H, Jackson ML. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a global cross-sectional survey. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021; 109:110236. PMID: 33373680.31. Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Fingerman KL, Polenick CA, Oya A. Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the covid-19 pandemic: implications for psychological well-being. Gerontologist. 2021; 61(2):205–216. PMID: 33346806.32. Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Suspected risk factors for depression among adults 18-44 years old. Epidemiology. 1991; 2(2):123–132. PMID: 1932309.33. Shin C, Kim Y, Park S, Yoon S, Ko YH, Kim YK, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(11):1861–1869. PMID: 28960042.34. Jefferis BJ, Nazareth I, Marston L, Moreno-Kustner B, Bellón JÁ, Svab I, et al. Associations between unemployment and major depressive disorder: evidence from an international, prospective study (the predict cohort). Soc Sci Med. 2011; 73(11):1627–1634. PMID: 22019370.35. Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, Chow W, Joshi K, Lefebvre P, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the united states. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021; 82(2):29169.36. Kim S, Ko Y, Kim YJ, Jung E. The impact of social distancing and public behavior changes on COVID-19 transmission dynamics in the Republic of Korea. PLoS One. 2020; 15(9):e0238684. PMID: 32970716.37. Johnson AF, Roberto KJ. The COVID-19 pandemic: time for a universal basic income? Public Adm Dev. 2020; 40(4):232–235. PMID: 33230360.38. Tzu-Hsuan Chen D. The psychosocial impact of the covid-19 pandemic on changes in smoking behavior: evidence from a nationwide survey in the UK. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020; 6:59. PMID: 33163705.39. Torres OV, O’Dell LE. Stress is a principal factor that promotes tobacco use in females. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016; 65:260–268. PMID: 25912856.40. Stubbs B, Veronese N, Vancampfort D, Prina AM, Lin PY, Tseng PT, et al. Perceived stress and smoking across 41 countries: a global perspective across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1):7597. PMID: 28790418.41. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999; 156(6):837–841. PMID: 10360120.42. Mulsant BH, Ganguli M, Seaberg EC. The relationship between self-rated health and depressive symptoms in an epidemiological sample of community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997; 45(8):954–958. PMID: 9256848.43. Ambresin G, Chondros P, Dowrick C, Herrman H, Gunn JM. Self-rated health and long-term prognosis of depression. Ann Fam Med. 2014; 12(1):57–65. PMID: 24445104.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Mental health of Korean adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special report of the 2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- Depression, Health-Related Habits, Eating Habits, and Nutrient Intake of Male Youth Before and After the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic -Analysis of the 2018 and 2020 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-

- Depression in pregnant and postpartum women during COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Changes in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korean adults after the COVID-19 outbreak

- Factors Associated with Depression in Older Adults Living Alone during the COVID-19 Pandemic