Arch Hand Microsurg.

2022 Dec;27(4):279-284. 10.12790/ahm.22.0054.

Comparison of ulnar shortening osteotomy for idiopathic ulnar impaction syndrome using conventional or ulnar osteotomy plates and with or without interfragmentary screw fixation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea

- 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 3Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Naeunpil Hospital, Cheonan, Korea

- KMID: 2536212

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12790/ahm.22.0054

Abstract

- Purpose

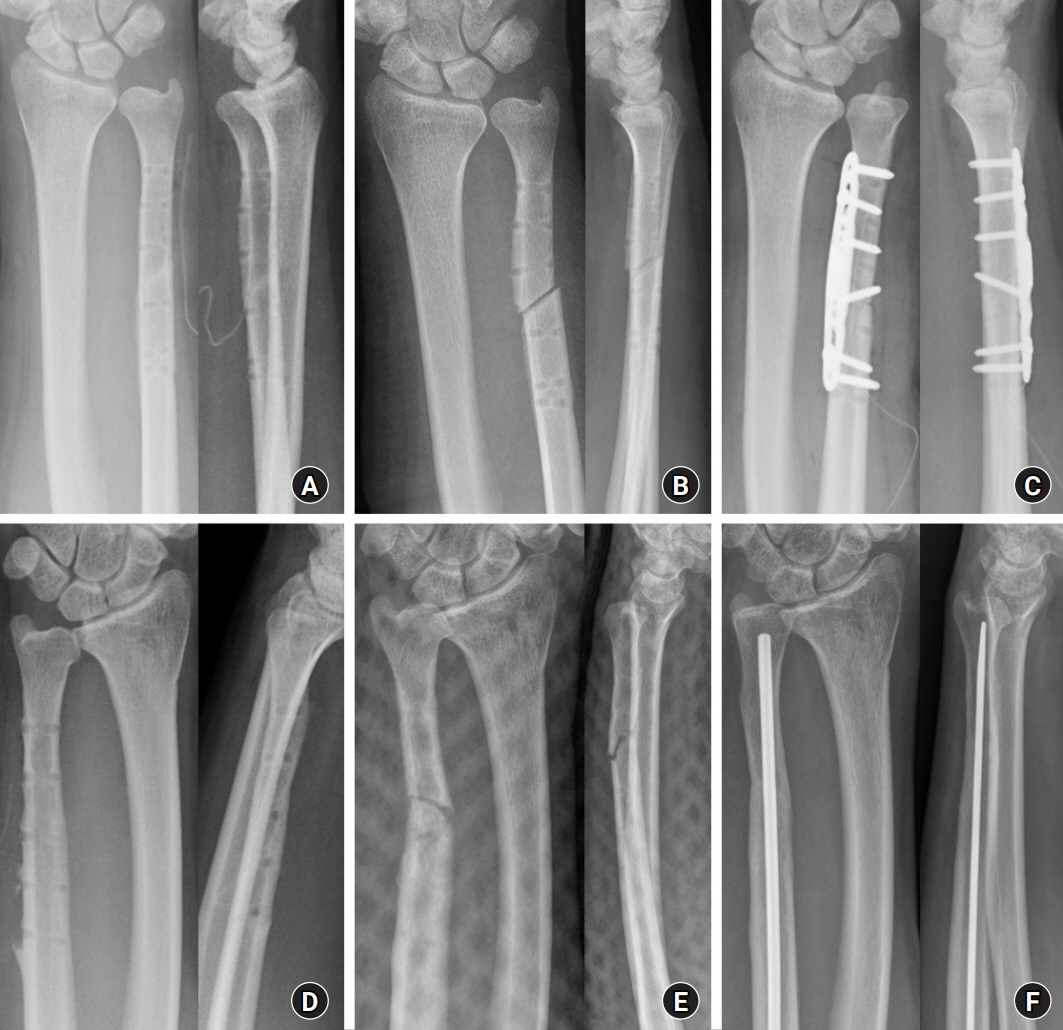

This study investigated the impact of plate type on the clinical and radiological outcomes of ulnar shortening osteotomy (USO) by comparing conventional and ulnar osteotomy plates. The effect of interfragmentary screw fixation (ISF) during USO was also assessed.

Methods

Seventy-eight patients were divided into three groups according to the type of plate: 3.5-mm dynamic compression plate (DCP), 3.5-mm limited contact DCP, and 2.7-mm locking compression plate ulna osteotomy system (all from Depuy-Synthes). The patients were also divided into two groups according to whether ISF was performed. Clinical and radiological outcomes, including time to bone union, presence of delayed union, and refracture after hardware removal, were analyzed. Other factors that might affect bone union, such as smoking and underlying diseases, were also evaluated.

Results

No significant differences were found in clinical and radiological outcomes according to the type of plate. Eight of 51 patients (15.7%) in the without-ISF group showed delayed bone union. Forty-three patients in the without-ISF group underwent hardware removal, and refracture due to low-energy trauma after hardware removal was observed in five of those 43 patients (11.6%). Bone union time was significantly shorter in the with-ISF group (7.6±2.7 weeks vs. 9.8±6.6 weeks). Diabetes mellitus and ISF were associated with the delayed bone union.

Conclusion

The plate type had no influence on the clinical and radiological outcomes of USO in patients with idiopathic ulnar impaction syndrome. However, ISF during USO has several advantages, such as early bony union and prevention of refracture after hardware removal.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Friedman SL, Palmer AK, Short WH, Levinsohn EM, Halperin LS. The change in ulnar variance with grip. J Hand Surg Am. 1993; 18:713–6.

Article2. Palmer AK, Glisson RR, Werner FW. Ulnar variance determination. J Hand Surg Am. 1982; 7:376–9.

Article3. Milch H. Cuff resection of the ulna for malunited Colles’ fracture. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941; 23:311–3.4. Baek GH, Chung MS, Lee YH, Gong HS, Lee S, Kim HH. Ulnar shortening osteotomy in idiopathic ulnar impaction syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87:2649–54.

Article5. Chun S, Palmer AK. The ulnar impaction syndrome: follow-up of ulnar shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 1993; 18:46–53.

Article6. Minami A, Kato H. Ulnar shortening for triangular fibrocartilage complex tears associated with ulnar positive variance. J Hand Surg Am. 1998; 23:904–8.

Article7. Constantine KJ, Tomaino MM, Herndon JH, Sotereanos DG. Comparison of ulnar shortening osteotomy and the wafer resection procedure as treatment for ulnar impaction syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2000; 25:55–60.

Article8. Vandenberghe L, Degreef I, Didden K, Moermans A, Koorneef P, De Smet L. Ulnar shortening or arthroscopic wafer resection for ulnar impaction syndrome. Acta Orthop Belg. 2012; 78:323–6.9. Jungwirth-Weinberger A, Borbas P, Schweizer A, Nagy L. Influence of plate size and design upon healing of ulna-shortening osteotomies. J Wrist Surg. 2016; 5:284–9.

Article10. Hulsizer D, Weiss AP, Akelman E. Ulna-shortening osteotomy after failed arthroscopic debridement of the triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Hand Surg Am. 1997; 22:694–8.

Article11. Magee W, Hettwer W, Badra M, Bay B, Hart R. Biomechanical comparison of a fully threaded, variable pitch screw and a partially threaded lag screw for internal fixation of type II dens fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007; 32:E475–9.

Article12. Chen NC, Wolfe SW. Ulna shortening osteotomy using a compression device. J Hand Surg Am. 2003; 28:88–93.

Article13. Darlis NA, Ferraz IC, Kaufmann RW, Sotereanos DG. Step-cut distal ulnar-shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2005; 30:943–8.

Article14. Mizuseki T, Tsuge K, Ikuta Y. Precise ulna-shortening osteotomy with a new device. J Hand Surg Am. 2001; 26:931–9.

Article15. Van Sanden S, De Smet L. Ulnar shortening after failed arthroscopic treatment of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Chir Main. 2001; 20:332–6.

Article16. Wehbé MA, Cautilli DA. Ulnar shortening using the AO small distractor. J Hand Surg Am. 1995; 20:959–64.

Article17. Chen F, Osterman AL, Mahony K. Smoking and bony union after ulna-shortening osteotomy. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2001; 30:486–9.18. Gaspar MP, Kane PM, Zohn RC, Buckley T, Jacoby SM, Shin EK. Variables prognostic for delayed union and nonunion following ulnar shortening fixed with a dedicated osteotomy plate. J Hand Surg Am. 2016; 41:237–43.

Article19. Pomerance J. Plate removal after ulnar-shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2005; 30:949–53.

Article20. Mih AD, Cooney WP, Idler RS, Lewallen DG. Long-term follow-up of forearm bone diaphyseal plating. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994; (299):256–8.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ulnar Shortening Osteotomy for the Treatment of Ulnar Impaction Syndrome

- Arthroscopy of the Wrist and Ulnar Shortening Osteotomy for the Treatment of the Ulnar Impaction Syndrome

- Long-term Outcomes of Ulnar Shortening Osteotomy for Idiopathic Ulnar Impaction Syndrome: At Least 5-Years Follow-up

- Treatment of Ulnar Impaction Syndrome using Arthroscopy and Ulnar Shortening Osteotomy

- Updates on Ulnar Impaction Syndrome