J Pathol Transl Med.

2022 Nov;56(6):354-360. 10.4132/jptm.2022.09.05.

Diagnostic distribution and pitfalls of glandular abnormalities in cervical cytology: a 25-year single-center study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pathology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2School of Medicine, European University Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

- 3Center for Medical Innovation, Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2535855

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2022.09.05

Abstract

- Background

Detection of glandular abnormalities in Papanicolaou (Pap) tests is challenging. This study aimed to review our institute’s experience interpreting such abnormalities, assess cytohistologic concordance, and identify cytomorphologic features associated with malignancy in follow-up histology.

Methods

Patients with cytologically-detected glandular lesions identified in our pathology records from 1995 to 2020 were included in this study.

Results

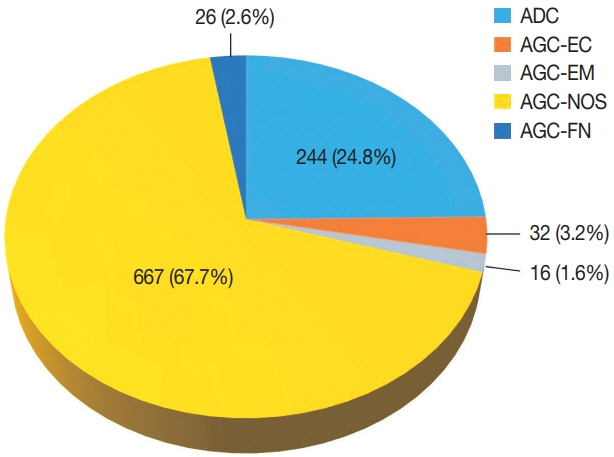

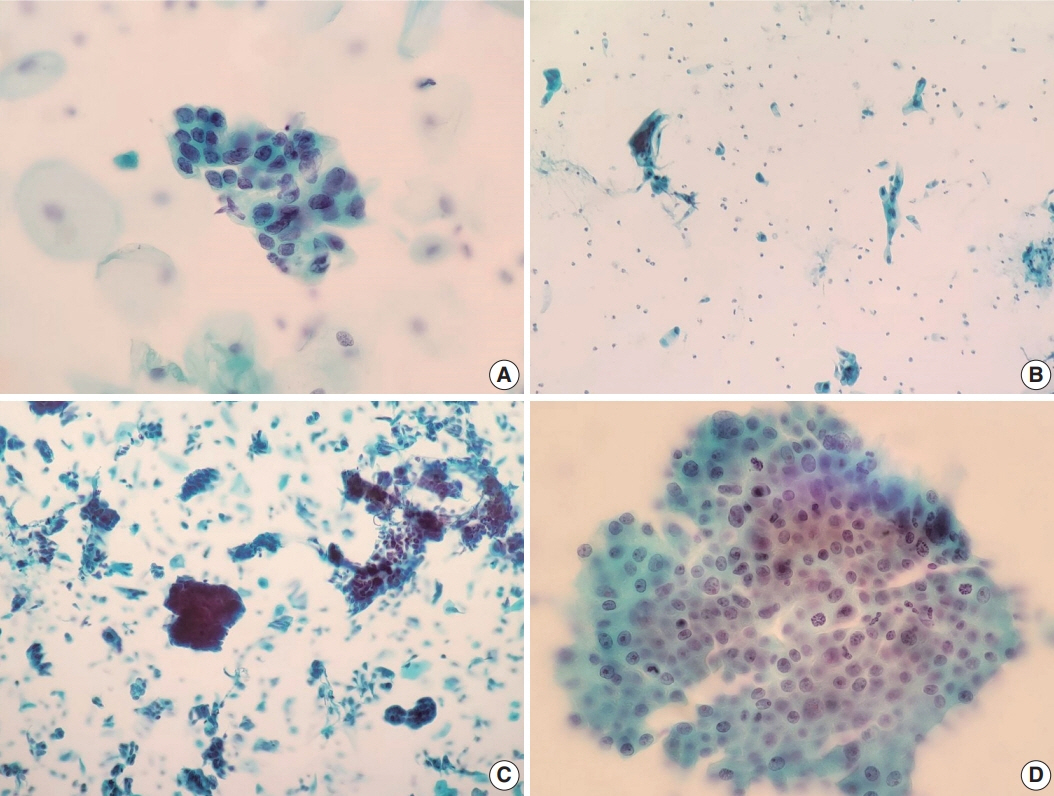

Of the 683,197 Pap tests performed, 985 (0.144%) exhibited glandular abnormalities, 657 of which had tissue follow-up available. One hundred eighty-eight cases were cytologically interpreted as adenocarcinoma and histologically diagnosed as malignant tumors of various origins. There were 213 cases reported as atypical glandular cells (AGC) and nine cases as adenocarcinoma in cytology, yet they were found to be benign in follow-up histology. In addition, 48 cases diagnosed with AGC and six with adenocarcinoma cytology were found to have cervical squamous lesions in follow-up histology, including four squamous cell carcinomas. Among the cytomorphological features examined, nuclear membrane irregularity, three-dimensional clusters, single-cell pattern, and presence of mitoses were associated with malignant histology in follow-up.

Conclusions

This study showed our institute’s experience detecting glandular abnormalities in cervical cytology over a 25-year period, revealing the difficulty of this task. Nonetheless, the present study indicates that several cytological findings such as membrane irregularity, three-dimensional clusters, single-cell pattern, and evidence of proliferation could help distinguishing malignancy from a benign lesion.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Warren R. Screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2013; 2:35.

Article2. Arbyn M, Rebolj M, De Kok IM, et al. The challenges of organising cervical screening programmes in the 15 old member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer. 2009; 45:2671–8.

Article3. Hong S, Won YJ, Park YR, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2017. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52:335–50.

Article4. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209–49.

Article5. Nayar R, Wilbur DC. The Pap test and Bethesda 2014. “The reports of my demise have been greatly exaggerated.” (after a quotation from Mark Twain). Acta Cytol. 2015; 59:121–32.6. Kang M, Ha SY, Cho HY, et al. Comparison of papanicolaou smear and human papillomavirus (HPV) test as cervical screening tools: can we rely on HPV test alone as a screening method? An 11-year retrospective experience at a single institution. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020; 54:112–8.

Article7. Polman NJ, Snijders PJ, Kenter GG, Berkhof J, Meijer C. HPV-based cervical screening: rationale, expectations and future perspectives of the new Dutch screening programme. Prev Med. 2019; 119:108–17.

Article8. Naucler P, Ryd W, Tornberg S, et al. Efficacy of HPV DNA testing with cytology triage and/or repeat HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009; 101:88–99.

Article9. Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Palmer T, Arbyn M. Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J Clin Virol. 2016; 76 Suppl 1:S49–S55.

Article10. Moriarty AT, Wilbur D. Those gland problems in cervical cytology: faith or fact? Observations from the Bethesda 2001 terminology conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003; 28:171–4.

Article11. Bansal B, Gupta P, Gupta N, Rajwanshi A, Suri V. Detecting uterine glandular lesions: role of cervical cytology. Cytojournal. 2016; 13:3.

Article12. Lin M, Narkcham S, Jones A, et al. False-negative Papanicolaou tests in women with biopsy-proven invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma/adenocarcinoma in situ: a retrospective analysis with assessment of interobserver agreement. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2022; 11:3–12.

Article13. Solomon D, Frable WJ, Vooijs GP, et al. ASCUS and AGUS criteria. International Academy of Cytology Task Force summary. Diagnostic cytology towards the 21st century: an international expert conference and tutorial. Acta Cytol. 1998; 42:16–24.14. Wood MD, Horst JA, Bibbo M. Weeding atypical glandular cell look-alikes from the true atypical lesions in liquid-based Pap tests: a review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007; 35:12–7.

Article15. Toyoda S, Kawaguchi R, Kobayashi H. Clinicopathological characteristics of atypical glandular cells determined by cervical cytology in Japan: survey of gynecologic oncology data from the Obstetrical Gynecological Society of Kinki District, Japan. Acta Cytol. 2019; 63:361–70.

Article16. Galic V, Herzog TJ, Lewin SN, et al. Prognostic significance of adenocarcinoma histology in women with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012; 125:287–91.

Article17. Gallardo-Alvarado L, Cantu-de Leon D, Ramirez-Morales R, et al. Tumor histology is an independent prognostic factor in locally advanced cervical carcinoma: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2022; 22:401.

Article18. Smith HO, Tiffany MF, Qualls CR, Key CR. The rising incidence of adenocarcinoma relative to squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in the United States: a 24-year population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000; 78:97–105.

Article19. Vizcaino AP, Moreno V, Bosch FX, et al. International trends in incidence of cervical cancer: II. Squamous-cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000; 86:429–35.

Article20. Wang SS, Sherman ME, Hildesheim A, Lacey JV Jr, Devesa S. Cervical adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma incidence trends among white women and black women in the United States for 1976-2000. Cancer. 2004; 100:1035–44.

Article21. Bray F, Loos AH, McCarron P, et al. Trends in cervical squamous cell carcinoma incidence in 13 European countries: changing risk and the effects of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005; 14:677–86.

Article22. Takeuchi S. Biology and treatment of cervical adenocarcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2016; 28:254–62.

Article23. Gien LT, Beauchemin MC, Thomas G. Adenocarcinoma: a unique cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010; 116:140–6.

Article24. Katanyoo K, Sanguanrungsirikul S, Manusirivithaya S. Comparison of treatment outcomes between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012; 125:292–6.

Article25. Zhao C, Florea A, Onisko A, Austin RM. Histologic follow-up results in 662 patients with Pap test findings of atypical glandular cells: results from a large academic womens hospital laboratory employing sensitive screening methods. Gynecol Oncol. 2009; 114:383–9.

Article26. Nayar R, Wilbur DC. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: definitions, criteria, and explanatory notes. Cham: Springer;2015.27. Oh EJ, Jung CK, Kim DH, et al. Current cytology practices in Korea: a nationwide survey by the Korean Society for Cytopathology. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017; 51:579–87.

Article28. Ajit D, Gavas S, Joseph S, Rekhi B, Deodhar K, Kane S. Identification of atypical glandular cells in pap smears: is it a hit and miss scenario? Acta Cytol. 2013; 57:45–53.

Article29. Yucel Polat A, Tepeoglu M, Tunca MZ, Ayva ES, Ozen O. Atypical glandular cells in Papanicolaou test: which is more important in the detection of malignancy, architectural or nuclear features? Cytopathology. 2021; 32:344–52.

Article30. Niu S, Molberg K, Thibodeaux J, et al. Challenges in the Pap diagnosis of endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019; 8:141–8.

Article31. Chaump M, Pirog EC, Panico VJ, AB DM, Holcomb K, Hoda R. Detection of in situ and invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma on ThinPrep Pap test: morphologic analysis of false negative cases. Cytojournal. 2016; 13:28.

Article32. Umezawa T, Umemori M, Horiguchi A, et al. Cytological variations and typical diagnostic features of endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ: a retrospective study of 74 cases. Cytojournal. 2015; 12:8.

Article33. Li S, Tian D, Li Y. Cytological diagnoses of adenocarcinoma in situ of the cervix: common misdiagnoses. Acta Cytol. 2015; 59:91–6.

Article34. Pradhan D, Li Z, Ocque R, Patadji S, Zhao C. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells in Pap tests: an analysis of more than 3000 cases at a large academic women’s center. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016; 124:589–95.

Article35. Raab SS, Isacson C, Layfield LJ, Lenel JC, Slagel DD, Thomas PA. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. Cytologic criteria to separate clinically significant from benign lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995; 104:574–82.

Article36. Torres JC, Derchain SF, Gontijo RC, et al. Atypical glandular cells: criteria to discriminate benign from neoplastic lesions and squamous from glandular neoplasia. Cytopathology. 2005; 16:295–302.37. Reynolds JP, Salih ZT, Smith AL, Dairi M, Kigen OJ, Nassar A. Cytologic parameters predicting neoplasia in Papanicolaou smears with atypical glandular cells and histologic follow-up: a single-institution experience. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2018; 7:7–15.

Article38. Selvaggi SM. Cytologic features of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions involving endocervical glands on ThinPrep cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002; 26:181–5.

Article39. Kumar N, Bongiovanni M, Molliet MJ, Pelte MF, Egger JF, Pache JC. Diverse glandular pathologies coexist with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion in cyto-histological review of atypical glandular cells on ThinPrep specimens. Cytopathology. 2009; 20:351–8.

Article40. Colgan TJ, Lickrish GM. The topography and invasive potential of cervical adenocarcinoma in situ, with and without associated squamous dysplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 1990; 36:246–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cytologic Findings of Cerebrospinal Fluid

- Risk factors of High Grade Lesions in Glandular Cell Abnormalities on Cervical Cytology

- The Clinical Evaluation of Triple Combined Test [ Cytology, HPV DNA Test, Cervicography] for Uterine Cervical Cancer

- Diagnostic Pitfalls in Breast Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology: False Positive and False Negative

- Histologic Correlation of Atypical Glandular Cells in Cervical Smears