Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2022 Sep;26(5):313-323. 10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.5.313.

Protective effect of low-intensity treadmill exercise against acetylcholine-calcium chloride-induced atrial fibrillation in mice

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Sport and Health Studies, College of Biomedical and Health Science, Konkuk University, Chungju 27478, Korea

- 2Sports Convergence Institute, Konkuk University, Chungju 27478, Korea

- 3Center for Metabolic Diseases, Konkuk University, Chungju 27478, Korea

- 4Department of Physical Education at the Graduate School of Education, Dankook University, Yongin 16890, Korea

- 5Department of Physiology, KU Open Innovation Center, Research Institute of Medical Science, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Chungju 27478, Korea

- 6Department of Emergency Medical Services, College of Health Sciences, Eulji University, Seongam 13135, Korea

- KMID: 2532761

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.5.313

Abstract

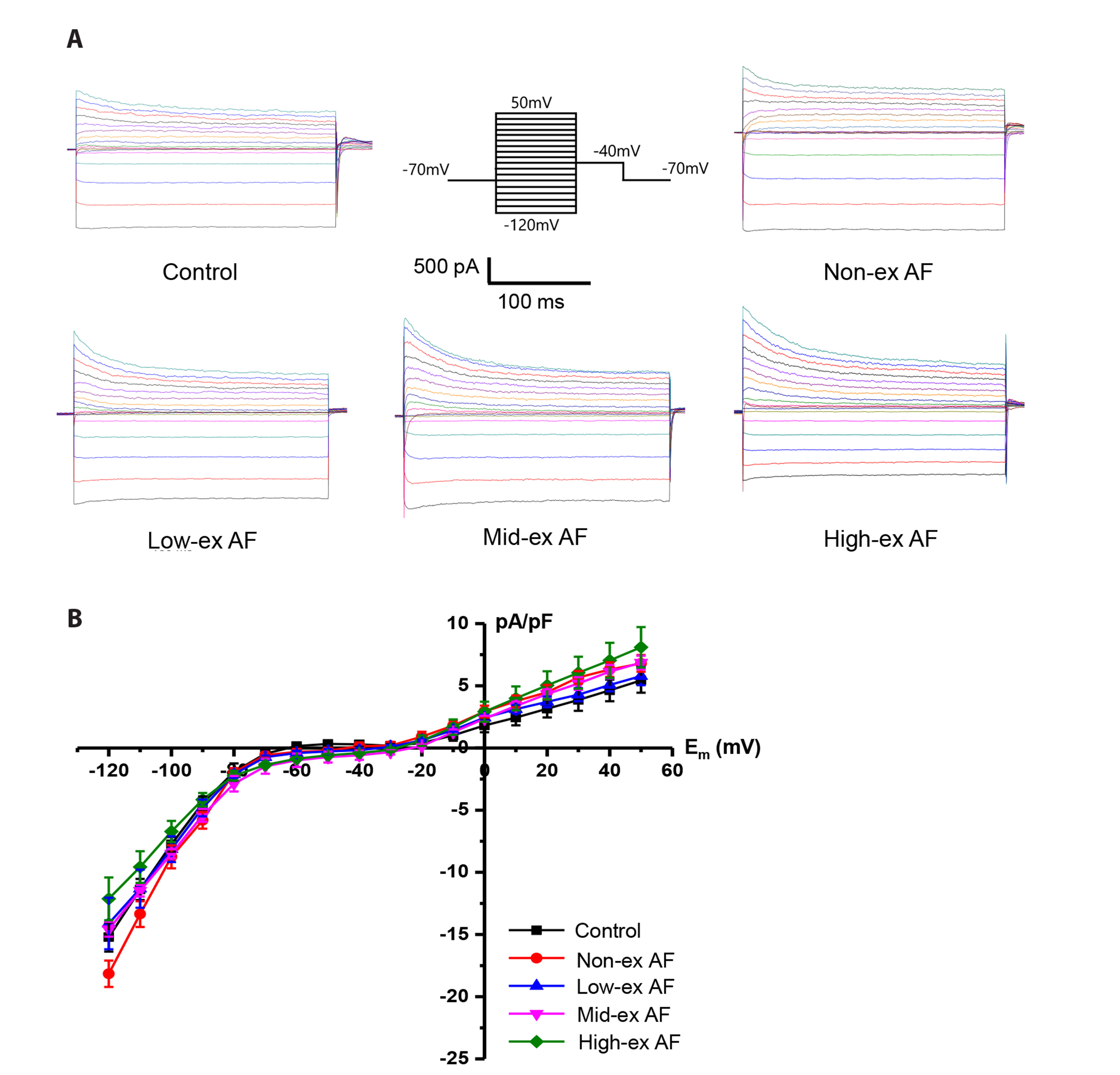

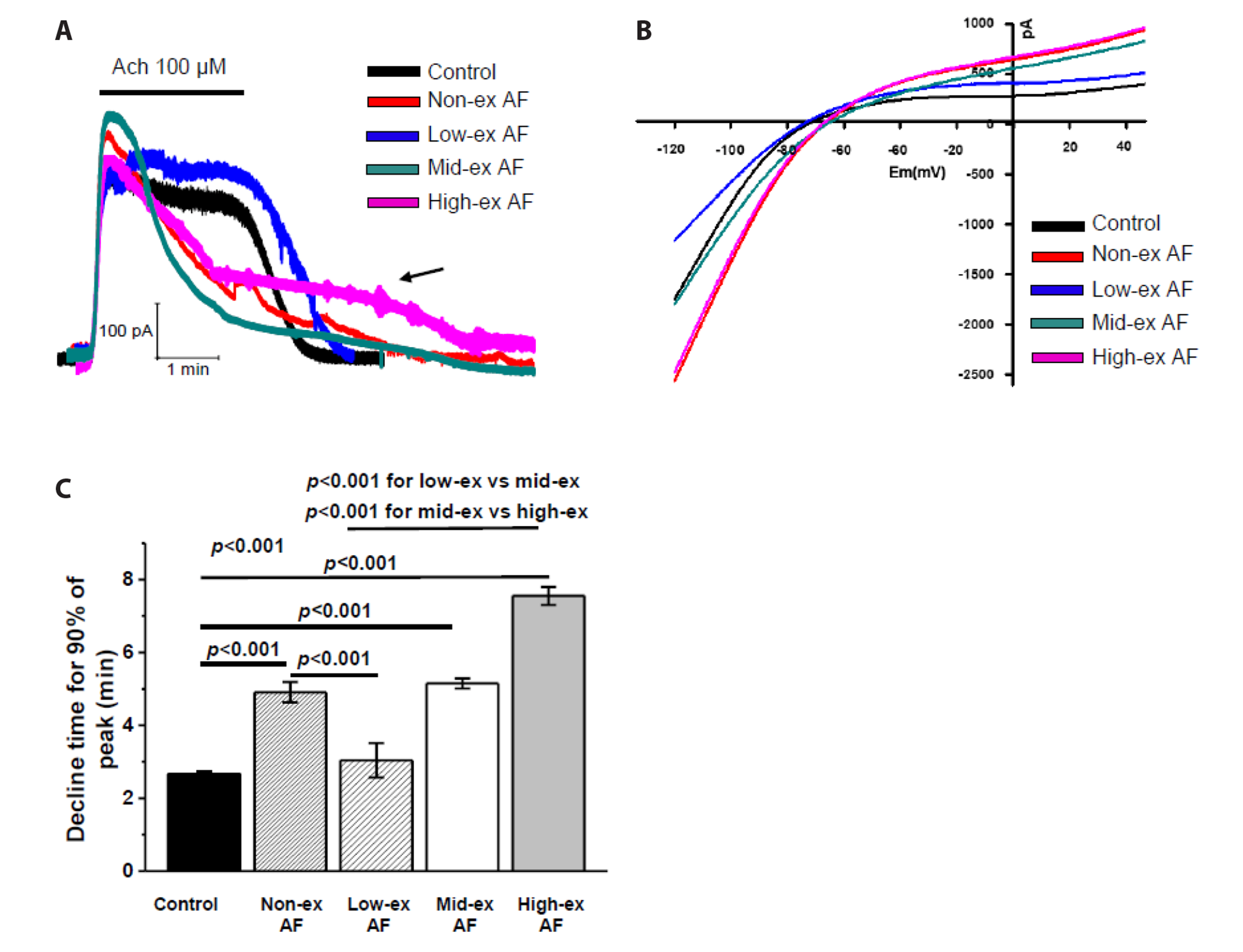

- Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common supraventricular arrhythmia, and it corresponds highly with exercise intensity. Here, we induced AF in mice using acetylcholine (ACh)-CaCl2 for 7 days and aimed to determine the appropriate exercise intensity (no, low, moderate, high) to protect against AF by running the mice at different intensities for 4 weeks before the AF induction by ACh-CaCl2 . We examined the AF-induced atrial remodeling using electrocardiogram, patch-clamp, and immunohistochemistry. After the AF induction, heart rate, % increase of heart rate, and heart weight/body weight ratio were significantly higher in all the four AF groups than in the normal control; highest in the high-ex AF and lowest in the low-ex (lower than the no-ex AF), which indicates that low-ex treated the AF. Consistent with these changes, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K + currents, which were induced by ACh, increased in an exercise intensity-dependent manner and were lower in the low-ex AF than the no-ex AF. The peak level of Ca2+ current (at 0 mV) increased also in an exercise intensity-dependent manner and the inactivation time constants were shorter in all AF groups except for the low-ex AF group, in which the time constant was similar to that of the control. Finally, action potential duration was shorter in all the four AF groups than in the normal control; shortest in the high-ex AF and longest in the low-ex AF. Taken together, we conclude that low-intensity exercise protects the heart from AF, whereas high-intensity exercise might exacerbate AF.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nattel S. 2002; New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 415:219–226. DOI: 10.1038/415219a. PMID: 11805846.

Article2. Thompson PD, Buchner D, Pina IL, Balady GJ, Williams MA, Marcus BH, Berra K, Blair SN, Costa F, Franklin B, Fletcher GF, Gordon NF, Pate RR, Rodriguez BL, Yancey AK, Wenger NK. 2003; Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee on Physical Activity). Circulation. 107:3109–3116. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000075572.40158.77. PMID: 12821592.

Article3. Grimsmo J, Grundvold I, Maehlum S, Arnesen H. 2010; High prevalence of atrial fibrillation in long-term endurance cross-country skiers: echocardiographic findings and possible predictors--a 28-30 years follow-up study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 17:100–105. DOI: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32833226be. PMID: 20065854.

Article4. Myrstad M, Løchen ML, Graff-Iversen S, Gulsvik AK, Thelle DS, Stigum H, Ranhoff AH. 2014; Increased risk of atrial fibrillation among elderly Norwegian men with a history of long-term endurance sport practice. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 24:e238–e244. DOI: 10.1111/sms.12150. PMID: 24256074. PMCID: PMC4282367.5. Grunnet M, Bentzen BH, Sørensen US, Diness JG. 2012; Cardiac ion channels and mechanisms for protection against atrial fibrillation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 162:1–58. DOI: 10.1007/112_2011_3. PMCID: PMC3014275. PMID: 21987061.

Article6. Schotten U, Neuberger HR, Allessie MA. 2003; The role of atrial dilatation in the domestication of atrial fibrillation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 82:151–162. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00012-9. PMID: 12732275.

Article7. Pelliccia A, Maron BJ, Di Paolo FM, Biffi A, Quattrini FM, Pisicchio C, Roselli A, Caselli S, Culasso F. 2005; Prevalence and clinical significance of left atrial remodeling in competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 46:690–696. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.052. PMID: 16098437.

Article8. Li D, Fareh S, Leung TK, Nattel S. 1999; Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation. 100:87–95. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.1.87. PMID: 10393686.

Article9. Bosch RF, Scherer CR, Rüb N, Wöhrl S, Steinmeyer K, Haase H, Busch AE, Seipel L, Kühlkamp V. 2003; Molecular mechanisms of early electrical remodeling: transcriptional downregulation of ion channel subunits reduces I(Ca,L) and I(to) in rapid atrial pacing in rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol. 41:858–869. DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02922-4. PMID: 12628735.

Article10. Zhang H, Garratt CJ, Zhu J, Holden AV. 2005; Role of up-regulation of IK1 in action potential shortening associated with atrial fibrillation in humans. Cardiovasc Res. 66:493–502. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.020. PMID: 15914114.

Article11. Christ T, Boknik P, Wöhrl S, Wettwer E, Graf EM, Bosch RF, Knaut M, Schmitz W, Ravens U, Dobrev D. 2004; L-type Ca2+ current downregulation in chronic human atrial fibrillation is associated with increased activity of protein phosphatases. Circulation. 110:2651–2657. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145659.80212.6A. PMID: 15492323.

Article12. Diness JG, Bentzen BH, Sørensen US, Grunnet M. 2015; Role of calcium-activated potassium channels in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and therapy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 66:441–448. DOI: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000249. PMID: 25830485. PMCID: PMC4692285.

Article13. Amin AS, Tan HL, Wilde AA. 2010; Cardiac ion channels in health and disease. Heart Rhythm. 7:117–126. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.005. PMID: 19875343.

Article14. Fan X, Wang C, Wang N, Ou X, Liu H, Yang Y, Dang X, Zeng X, Cai L. 2016; Atrial-selective block of sodium channels by acehytisine in rabbit myocardium. J Pharmacol Sci. 132:235–243. DOI: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.03.014. PMID: 27107824.

Article15. Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. 2001; The contribution of ionic currents to changes in refractoriness of human atrial myocytes associated with chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 52:226–235. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00380-7. PMID: 11684070.

Article16. Yagi T, Pu J, Chandra P, Hara M, Danilo P Jr, Rosen MR, Boyden PA. 2002; Density and function of inward currents in right atrial cells from chronically fibrillating canine atria. Cardiovasc Res. 54:405–415. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00279-1. PMID: 12062345.

Article17. Gaborit N, Steenman M, Lamirault G, Le Meur N, Le Bouter S, Lande G, Léger J, Charpentier F, Christ T, Dobrev D, Escande D, Nattel S, Demolombe S. 2005; Human atrial ion channel and transporter subunit gene-expression remodeling associated with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 112:471–481. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.506857. PMID: 16027256.

Article18. Li N, Timofeyev V, Tuteja D, Xu D, Lu L, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Singapuri A, Albert TR, Rajagopal AV, Bond CT, Periasamy M, Adelman J, Chiamvimonvat N. 2009; Ablation of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK2 channel) results in action potential prolongation in atrial myocytes and atrial fibrillation. J Physiol. 587(Pt 5):1087–1100. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167718. PMID: 19139040. PMCID: PMC2673777.

Article19. Walsh KB. 2011; Targeting GIRK channels for the development of new therapeutic agents. Front Pharmacol. 2:64. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00064. PMID: 22059075. PMCID: PMC3204421.

Article20. Burke MA, Mutharasan RK, Ardehali H. 2008; The sulfonylurea receptor, an atypical ATP-binding cassette protein, and its regulation of the KATP channel. Circ Res. 102:164–176. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165324. PMID: 18239147.

Article21. Boyle WA, Nerbonne JM. 1992; Two functionally distinct 4-aminopyridine-sensitive outward K+ currents in rat atrial myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 100:1041–1067. DOI: 10.1085/jgp.100.6.1041. PMID: 1484284. PMCID: PMC2229143.

Article22. American Physiological Society. 2006. Resource book for the design of animal exercise protocols. American Physiological Society;p. 43–47. https://www.physiology.org/docs/default-source/science-policy/animalresearch/resource-book-for-the-design-of-animal-exercise-protocols.pdf?sfvrsn=43d9355b_12.23. Castro B, Kuang S. 2017; Evaluation of muscle performance in mice by treadmill exhaustion test and whole-limb grip strength assay. Bio Protoc. 7:e2237. DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2237. PMID: 28713848. PMCID: PMC5510664.

Article24. Zou D, Geng N, Chen Y, Ren L, Liu X, Wan J, Guo S, Wang S. 2016; Ranolazine improves oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in the atrium of acetylcholine-CaCl2 induced atrial fibrillation rats. Life Sci. 156:7–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.05.026. PMID: 27208652.

Article25. Morishima M, Iwata E, Nakada C, Tsukamoto Y, Takanari H, Miyamoto S, Moriyama M, Ono K. 2016; Atrial fibrillation-mediated upregulation of miR-30d regulates myocardial electrical remodeling of the G-protein-gated K+ channel, IK.ACh. Circ J. 80:1346–1355. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-1276. PMID: 27180889.

Article26. Guasch E, Benito B, Qi X, Cifelli C, Naud P, Shi Y, Mighiu A, Tardif JC, Tadevosyan A, Chen Y, Gillis MA, Iwasaki YK, Dobrev D, Mont L, Heximer S, Nattel S. 2013; Atrial fibrillation promotion by endurance exercise: demonstration and mechanistic exploration in an animal model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 62:68–77. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.091. PMID: 23583240.27. La Gerche A, Robberecht C, Kuiperi C, Nuyens D, Willems R, de Ravel T, Matthijs G, Heidbüchel H. 2010; Lower than expected desmosomal gene mutation prevalence in endurance athletes with complex ventricular arrhythmias of right ventricular origin. Heart. 96:1268–1274. DOI: 10.1136/hrt.2009.189621. PMID: 20525856.

Article28. Benito B, Gay-Jordi G, Serrano-Mollar A, Guasch E, Shi Y, Tardif JC, Brugada J, Nattel S, Mont L. 2011; Cardiac arrhythmogenic remodeling in a rat model of long-term intensive exercise training. Circulation. 123:13–22. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.938282. PMID: 21173356.

Article29. Baldesberger S, Bauersfeld U, Candinas R, Seifert B, Zuber M, Ritter M, Jenni R, Oechslin E, Luthi P, Scharf C, Marti B, Attenhofer Jost CH. 2008; Sinus node disease and arrhythmias in the long-term follow-up of former professional cyclists. Eur Heart J. 29:71–78. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm555. PMID: 18065754.

Article30. Molina L, Mont L, Marrugat J, Berruezo A, Brugada J, Bruguera J, Rebato C, Elosua R. 2008; Long-term endurance sport practice increases the incidence of lone atrial fibrillation in men: a follow-up study. Europace. 10:618–623. DOI: 10.1093/europace/eun071. PMID: 18390875.

Article31. Aizer A, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Albert CM. 2009; Relation of vigorous exercise to risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 103:1572–1577. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.374. PMID: 19463518. PMCID: PMC2687527.32. Aschar-Sobbi R, Izaddoustdar F, Korogyi AS, Wang Q, Farman GP, Yang F, Yang W, Dorian D, Simpson JA, Tuomi JM, Jones DL, Nanthakumar K, Cox B, Wehrens XH, Dorian P, Backx PH. 2015; Increased atrial arrhythmia susceptibility induced by intense endurance exercise in mice requires TNFα. Nat Commun. 6:6018. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7018. PMID: 25598495. PMCID: PMC4661059.

Article33. Tai CT, Chiou CW, Wen ZC, Hsieh MH, Tsai CF, Lin WS, Chen CC, Lin YK, Yu WC, Ding YA, Chang MS, Chen SA. 2000; Effect of phenylephrine on focal atrial fibrillation originating in the pulmonary veins and superior vena cava. J Am Coll Cardiol. 36:788–793. DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00792-0. PMID: 10987601.

Article34. Dobrev D, Friedrich A, Voigt N, Jost N, Wettwer E, Christ T, Knaut M, Ravens U. 2005; The G protein-gated potassium current IK,ACh is constitutively active in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 112:3697–3706. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575332. PMID: 16330682.

Article35. Wilhelm M, Roten L, Tanner H, Wilhelm I, Schmid JP, Saner H. 2011; Atrial remodeling, autonomic tone, and lifetime training hours in nonelite athletes. Am J Cardiol. 108:580–585. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.086. PMID: 21658663.36. Kovoor P, Wickman K, Maguire CT, Pu W, Gehrmann J, Berul CI, Clapham DE. 2001; Evaluation of the role of IK,Ach in atrial fibrillation using a mouse knockout model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 37:2136–2143. DOI: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01304-3. PMID: 11419900.

Article37. De Angelis K, Wichi RB, Jesus WR, Moreira ED, Morris M, Krieger EM, Irigoyen MC. 2004; Exercise training changes autonomic cardiovascular balance in mice. J Appl Physiol (1985). 96:2174–2178. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00870.2003. PMID: 14729725.

Article38. Lee SW, Anderson A, Guzman PA, Nakano A, Tolkacheva EG, Wickman K. 2018; Atrial GIRK channels mediate the effects of vagus nerve stimulation on heart rate dynamics and arrhythmogenesis. Front Physiol. 9:943. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00943. PMID: 30072916. PMCID: PMC6060443.

Article39. Brundel BJ, Van Gelder IC, Henning RH, Tieleman RG, Tuinenburg AE, Wietses M, Grandjean JG, Van Gilst WH, Crijns HJ. 2001; Ion channel remodeling is related to intraoperative atrial effective refractory periods in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 103:684–690. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.5.684. PMID: 11156880.

Article40. Lugenbiel P, Wenz F, Govorov K, Schweizer PA, Katus HA, Thomas D. 2015; Atrial fibrillation complicated by heart failure induces distinct remodeling of calcium cycling proteins. PLoS One. 10:e0116395. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116395. PMID: 25775120. PMCID: PMC4361185. PMID: e2f014b698ac4f9c958e980f4e7348e5.

Article41. Wakili R, Yeh YH, Yan Qi X, Greiser M, Chartier D, Nishida K, Maguy A, Villeneuve LR, Boknik P, Voigt N, Krysiak J, Kääb S, Ravens U, Linke WA, Stienen GJ, Shi Y, Tardif JC, Schotten U, Dobrev D, Nattel S. 2010; Multiple potential molecular contributors to atrial hypocontractility caused by atrial tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 3:530–541. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.933036. PMID: 20660541.

Article42. Sung DJ, Kim JG, Won KJ, Kim B, Shin HC, Park JY, Bae YM. 2012; Blockade of K+ and Ca2+ channels by azole antifungal agents in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Biol Pharm Bull. 35:1469–1475. DOI: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00002. PMID: 22975497.

Article43. Dzeshka MS, Lip GY, Snezhitskiy V, Shantsila E. 2015; Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 66:943–959. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1313. PMID: 26293766.44. Hanif W, Alex L, Su Y, Shinde AV, Russo I, Li N, Frangogiannis NG. 2017; Left atrial remodeling, hypertrophy, and fibrosis in mouse models of heart failure. Cardiovasc Pathol. 30:27–37. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.06.003. PMID: 28759817. PMCID: PMC5592139.

Article45. Rosenberg MA, Das S, Quintero Pinzon P, Knight AC, Sosnovik DE, Ellinor PT, Rosenzweig A. 2012; A novel transgenic mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy and atrial fibrillation. J Atr Fibrillation. 4:415. DOI: 10.4022/jafib.415. PMID: 28496713. PMCID: PMC3521534.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Exercise-Induced Atrial Fibrillation

- Effects of Recumbent Bicycle Exercise on Cardiac Autonomic Responses and Hemodynamics Variables in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

- Effect of Regular Exercise on Platelet Cytoplasmic Calcium during Treatmill Exercise in Healthy Young Males

- Electrolyte’s imbalance role in atrial fibrillation: Pharmacological management

- Pathophysiology and Diagnosis in Atrial Fibrillation