Acute Crit Care.

2022 May;37(2):168-176. 10.4266/acc.2021.00920.

Comparison of critically ill COVID-19 and influenza patients with acute respiratory failure

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Intensive Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

- KMID: 2531673

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2021.00920

Abstract

- Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is one of the biggest pandemic causing acute respiratory failure (ARF) in the last century. Seasonal influenza carries high mortality, as well. The aim of this study was to compare features and outcomes of critically-ill COVID-19 and influenza patients with ARF.

Methods

Patients with COVID-19 and influenza admitted to intensive care unit with ARF were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

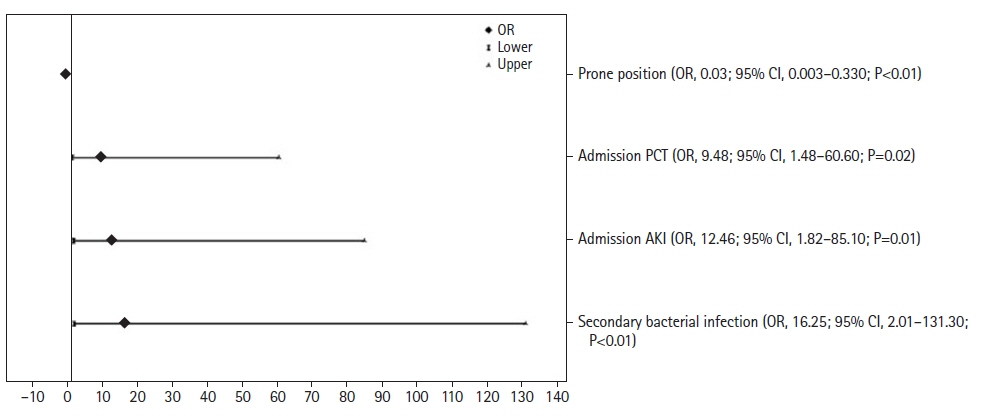

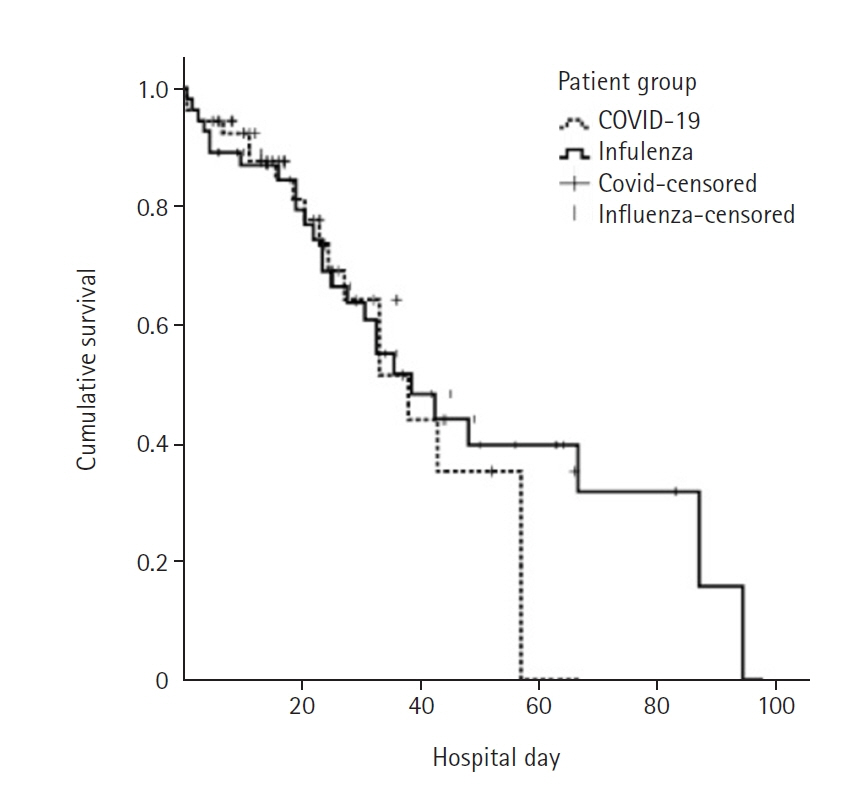

Fifty-four COVID-19 and 55 influenza patients with ARF were studied. Patients with COVID-19 had 32% of hospital mortality, while those with influenza had 47% (P=0.09). Patients with influenza had higher Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Clinical Frailty Scale, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II and admission Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores than COVID-19 patients (P<0.01). Secondary bacterial infection, admission acute kidney injury, procalcitonin level above 0.2 ng/ml were the independent factors distinguishing influenza from COVID-19 while prone positioning differentiated COVID-19 from influenza. Invasive mechanical ventilation (odds ratio [OR], 42.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.45–187.97), admission SOFA score more than 4 (OR, 5.92; 95% CI, 1.85–18.92), malignancy (OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.13–21.60), and age more than 65 years (OR, 3.31; 95% CI, 0.99–11.03) were found to be independent risk factors for hospital mortality.

Conclusions

There were few differences in clinical features of critically-ill COVID-19 and influenza patients. Influenza cases had worse performance status and disease severity. There was no significant difference in hospital mortality rates between COVID-19 and influenza patients.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 26:729–34.

Article2. Halacli B, Kaya A, Topeli A. Critically-ill COVID-19 patient. Turk J Med Sci. 2020; 50(SI-1):585–91.3. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020; 323:1239–42.

Article4. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8:475–81.

Article5. Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020; 180:1345–55.6. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020; 323:2052–9.

Article7. Ortiz JR, Neuzil KM, Shay DK, Rue TC, Neradilek MB, Zhou H, et al. The burden of influenza-associated critical illness hospitalizations. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42:2325–32.

Article8. Arabi YM, Fowler R, Hayden FG. Critical care management of adults with community-acquired severe respiratory viral infection. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46:315–28.

Article9. Ortac Ersoy E, Er B, Ciftci F, Gulleroglu A, Suner K, Arpinar B, et al. Outcome of patients admitted to intensive care units due to influenza-related severe acute respiratory illness in 2017-2018 flu season: a multicenter study from Turkey. Respiration. 2020; 99:954–60.

Article10. Tang X, Du RH, Wang R, Cao TZ, Guan LL, Yang CQ, et al. Comparison of hospitalized patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19 and H1N1. Chest. 2020; 158:195–205.

Article11. Zayet S, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Lepiller Q, Zahra H, Royer PY, Toko L, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 and influenza: a comparative study on Nord Franche-Comte cluster. Microbes Infect. 2020; 22:481–8.

Article12. Piroth L, Cottenet J, Mariet AS, Bonniaud P, Blot M, Tubert-Bitter P, et al. Comparison of the characteristics, morbidity, and mortality of COVID-19 and seasonal influenza: a nationwide, population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021; 9:251–9.

Article13. Schnell D, Gits-Muselli M, Canet E, Lemiale V, Schlemmer B, Simon F, et al. Burden of respiratory viruses in patients with acute respiratory failure. J Med Virol. 2014; 86:1198–202.

Article14. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315:801–10.

Article15. KDIGO. Clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012; 2(Suppl 1):1–138.16. Martín-Loeches I, Sanchez-Corral A, Diaz E, Granada RM, Zaragoza R, Villavicencio C, et al. Community-acquired respiratory coinfection in critically ill patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus. Chest. 2011; 139:555–62.

Article17. MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA, Barnes M, Ridda I, Seale H, Toms R, et al. The role of pneumonia and secondary bacterial infection in fatal and serious outcomes of pandemic influenza a(H1N1)pdm09. BMC Infect Dis. 2018; 18:637.

Article18. Zhao Z, Chen A, Hou W, Graham JM, Li H, Richman PS, et al. Prediction model and risk scores of ICU admission and mortality in COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020; 15:e0236618.

Article19. Meng FS, Su L, Tang YQ, Wen Q, Liu YS, Liu ZF. Serum procalcitonin at the time of admission to the ICU as a predictor of short-term mortality. Clin Biochem. 2009; 42:1025–31.

Article20. Demirjian SG, Raina R, Bhimraj A, Navaneethan SD, Gordon SM, Schreiber MJ Jr, et al. 2009 influenza A infection and acute kidney injury: incidence, risk factors, and complications. Am J Nephrol. 2011; 34:1–8.

Article21. Bagshaw SM, Sood MM, Long J, Fowler RA, Adhikari NK; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group H1N1 Collaborative. Acute kidney injury among critically ill patients with pandemic H1N1 influenza A in Canada: cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013; 14:123.

Article22. Beumer MC, Koch RM, van Beuningen D, OudeLashof AM, van de Veerdonk FL, Kolwijck E, et al. Influenza virus and factors that are associated with ICU admission, pulmonary co-infections and ICU mortality. J Crit Care. 2019; 50:59–65.

Article23. Pei G, Zhang Z, Peng J, Liu L, Zhang C, Yu C, et al. Renal involvement and early prognosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020; 31:1157–65.

Article24. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395:497–506.

Article25. Valenza F, Guglielmi M, Maffioletti M, Tedesco C, Maccagni P, Fossali T, et al. Prone position delays the progression of ventilator-induced lung injury in rats: does lung strain distribution play a role? Crit Care Med. 2005; 33:361–7.

Article26. Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, Hodgson CL, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 195:1253–63.

Article27. Elharrar X, Trigui Y, Dols AM, Touchon F, Martinez S, Prud’homme E, et al. Use of prone positioning in nonintubated patients with COVID-19 and hypoxemic acute respiratory failure. JAMA. 2020; 323:2336–8.

Article28. Weatherald J, Solverson K, Zuege DJ, Loroff N, Fiest KM, Parhar KK. Awake prone positioning for COVID-19 hypoxemic respiratory failure: a rapid review. J Crit Care. 2021; 61:63–70.

Article29. Halaçlı B, Hancı P, Ortaç Ersoy E, Öcal S, Tanrıöver MD, Topeli A. Influenza or other respiratory viruses: does it matter as the cause of acute respiratory failure in the critically-ill patients? Tuberk Toraks. 2020; 68:388–98.

Article30. Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, Leung V, Westwood D, MacFadden DR, et al. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 26:1622–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Experience of Treating Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients in Daegu, South Korea

- How We Have Treated Severe to Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Korea

- Risk factors associated with development of coinfection in critically Ill patients with COVID-19

- Characteristics of Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients in Busan, Republic of Korea