J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Jan;36(3):e33. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e33.

The Psychological Burden of COVID-19 Stigma: Evaluation of the Mental Health of Isolated Mild Condition COVID-19 Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Public Healthcare Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2510745

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e33

Abstract

- Background

The objective of this article is to assess the mental health issues of the mild condition coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients admitted to a community treatment center (CTC) in Korea.

Methods

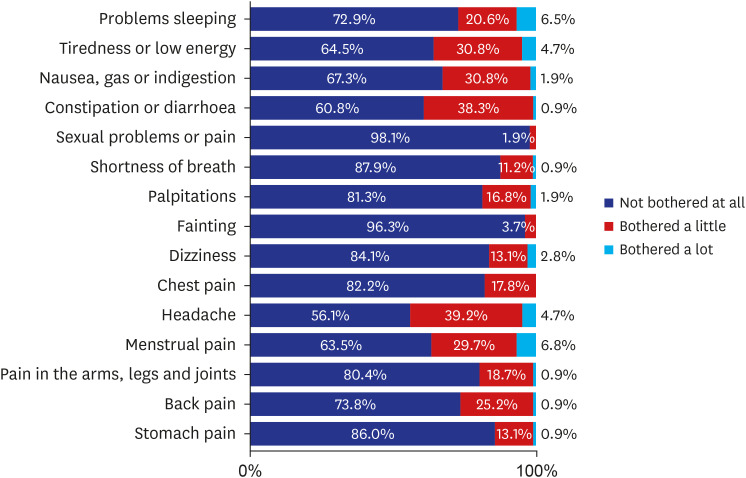

A total of 107 patients admitted to a CTC were included as the study population, and their mental health problems including depression (patient health questionnaire-9), anxiety (generalized anxiety disorder scale-7), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (PTSD checklist-5) and somatic symptoms (by patient health questionnaire-15) were evaluated every week during their stay. The stigma related to COVID-19 infection was evaluated with an adjusted version of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) stigma scale.

Results

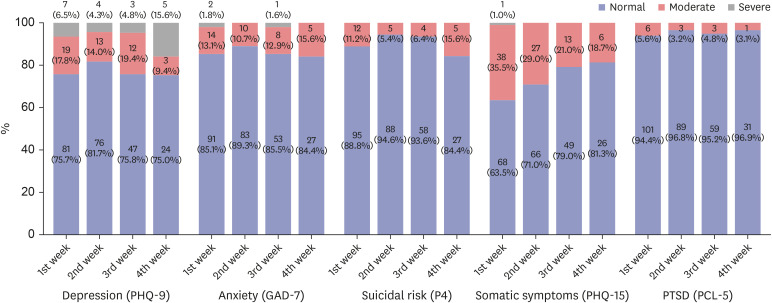

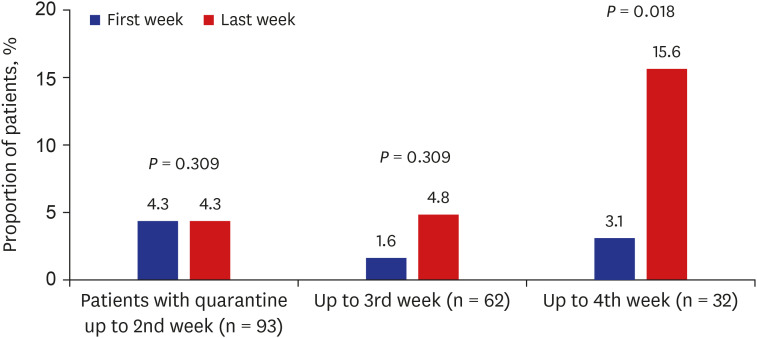

During the first week of isolation, the prevalence of more-than-moderate depression was 24.3%, more-than-moderate anxiety was 14.9%, more-than-moderate somatic symptoms was 36.5% and possible PTSD was 5.6% of total population. For depression and anxiety, previous psychiatric history and stigma of COVID-19 infection were significant risk factors. For PTSD, previous psychiatric history and stigma of COVID-19 infection as well as total duration of isolation were found to be significant risk factors. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and possible PTSD remained similar across the four weeks of observations, though the prevalence of severe depression, increased after four weeks of stay. Somatic symptoms seemed to decrease during their stay.

Conclusion

The results suggest that social mitigation of COVID-19 related stigma, as well as care of patients with pre-existing mental health problems are important mental health measures during this crisis period. It is also important that clinical guidelines and public health policies be well balanced over the protection of the public and those quarantined to minimize the negative psychosocial consequences from isolation of the patients.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Factors Related to Anxiety and Depression Among Adolescents During COVID-19: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey

Kyung-Shin Lee, Ho Kyung Sung, So Hee Lee, Jinhee Hyun, Heeguk Kim, Jong-Sun Lee, Jong-Woo Paik, Seok-Joo Kim, Sunju Sohn, Yun-Kyeung Choi

J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(25):e199. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e199.

Reference

-

1. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Korean Society of Epidemiology. Korean Society for Antimicrobial Therapy. Korean Society for Healthcare-associated Infection Control and Prevention. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 2, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(10):e112. PMID: 32174069.2. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage—allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(21):1973–1975. PMID: 32202721.3. Park PG, Kim CH, Heo Y, Kim TS, Park CW, Kim CH. Out-of-hospital cohort treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 patients with mild symptoms in Korea: an experience from a single community treatment center. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(13):e140. PMID: 32242347.

Article4. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18):1708–1720. PMID: 32109013.5. Gammon J. The psychological consequences of source isolation: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 1999; 8(1):13–21. PMID: 10214165.

Article6. Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ. 2020; 368:m313. PMID: 31992552.

Article7. Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10(7):1206–1212. PMID: 15324539.

Article8. Barbisch D, Koenig KL, Shih FY. Is there a case for quarantine? perspectives from SARS to Ebola. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015; 9(5):547–553. PMID: 25797363.

Article9. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020; 395(10227):912–920. PMID: 32112714.

Article10. Kim SW, Lee KS, Kim K, Lee JJ, Kim JY. Daegu Medical Association. A brief telephone severity scoring system and therapeutic living centers solved acute hospital-bed shortage during the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu, Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(15):e152. PMID: 32301298.

Article11. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Response Guideline. 8th ed. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2020.12. Kang E, Lee SY, Jung H, Kim MS, Cho B, Kim YS. Operating protocols of a community treatment center for isolation of patients with coronavirus disease, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(10):2329–2337. PMID: 32568665.

Article13. Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med. 2010; 8(4):348–353. PMID: 20644190.

Article14. Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016; 39:24–31. PMID: 26719105.

Article15. Dube P, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Theobald D, Williams LS. The p4 screener: evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 12(6):PCC.10m00978. PMID: 21494337.16. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs;2013.17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002; 64(2):258–266. PMID: 11914441.

Article18. An JY, Seo ER, Lim KH, Shin JH, Kim JB. Standardization of the Korean version of screening tool for depression (patient health questionnaire-9, PHQ-9). J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2013; 19(1):47–56.19. Ahn JK, Kim Y, Choi KH. The psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Korean version of GAD-7 and GAD-2. Front Psychiatry. 2019; 10:127. PMID: 30936840.

Article20. Kim JW, Chung HG, Choi JH, So HS, Kang SH, Kim DS, et al. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the PTSD checklist-5 in elderly Korean veterans of the Vietnam War. Anxiety Mood. 2017; 13(2):123–131.21. Park HY, Park WB, Lee SH, Kim JL, Lee JJ, Lee H, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression of survivors 12 months after the outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):605. PMID: 32410603.

Article22. Lyoo YC, Ju S, Kim E, Kim JE, Lee JH. The patient health questionnaire-15 and its abbreviated version as screening tools for depression in Korean college and graduate students. Compr Psychiatry. 2014; 55(3):743–748. PMID: 24342054.

Article23. Wiklander M, Rydström LL, Ygge BM, Navér L, Wettergren L, Eriksson LE. Psychometric properties of a short version of the HIV stigma scale, adapted for children with HIV infection. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013; 11(1):195. PMID: 24225077.

Article24. Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhu CY, Hong WC, Yu ZX, Chen ZK, et al. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:56–58. PMID: 32315758.

Article25. Stop the coronavirus stigma now. Nature. 2020; 580(7802):165. PMID: 32265571.26. Sternlicht A. With new COVID-19 outbreak linked to gay man, homophobia on rise in South Korea. Updated May 12, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrasternlicht/2020/05/12/with-new-covid-19-outbreak-linked-to-gay-man-homophobia-on-rise-in-south-korea/?sh=71c422149099.27. Shin H, Cha S. South Koreans call in petition for Chinese to be barred over virus. Updated January 28, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-reaction-southkorea/south-koreans-call-in-petition-for-chinese-to-be-barred-over-virus-idUSKBN1ZR0QJ.28. Kuo L, Davidson H. They see my blue eyes then jump back' – China sees a new wave of xenophobia. Updated March 29, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/29/china-coronavirus-anti-foreigner-feeling-imported-cases.29. Logie CH, Turan JM. How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS Behav. 2020; 24(7):2003–2006. PMID: 32266502.

Article30. UNICEF. Social stigma associated with COVID-19: a guide to preventing and addressing social stigma. Updated March 2020. https://www.unicef.org/documents/social-stigma-associated-coronavirus-disease-covid-19.31. Acarturk C, Cetinkaya M, Senay I, Gulen B, Aker T, Hinton D. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms among Syrian refugees in a refugee camp. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018; 206(1):40–45. PMID: 28632513.

Article32. Alpak G, Unal A, Bulbul F, Sagaltici E, Bez Y, Altindag A, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015; 19(1):45–50. PMID: 25195765.

Article33. Wang Y, Xu B, Zhao G, Cao R, He X, Fu S. Is quarantine related to immediate negative psychological consequences during the 2009 H1N1 epidemic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011; 33(1):75–77. PMID: 21353131.

Article34. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: IASC;2007.35. International Federation Reference Centre for Psychosocial Support. Psychosocial interventions A handbook. Copenhagen: International Federation Reference Centre for Psychosocial Support;2009.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Psychological Effects of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic

- Role of Stigma in Moderating the Effects of Loneliness on Mental Health Problems Among Patients With COVID-19 in South Korea

- Factors influencing stigma among college students with COVID-19 in South Korea: a descriptive study

- The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and chronic diseases

- Post-recovery Stigma in Early and Late COVID-19 Epidemic