Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2019 Nov;12(4):360-366. 10.21053/ceo.2018.01333.

Outcomes of Modified Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy and Mastoid Obliteration Using Autologous Materials

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon, Korea. ljdent@schmc.ac.kr

- KMID: 2462731

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2018.01333

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

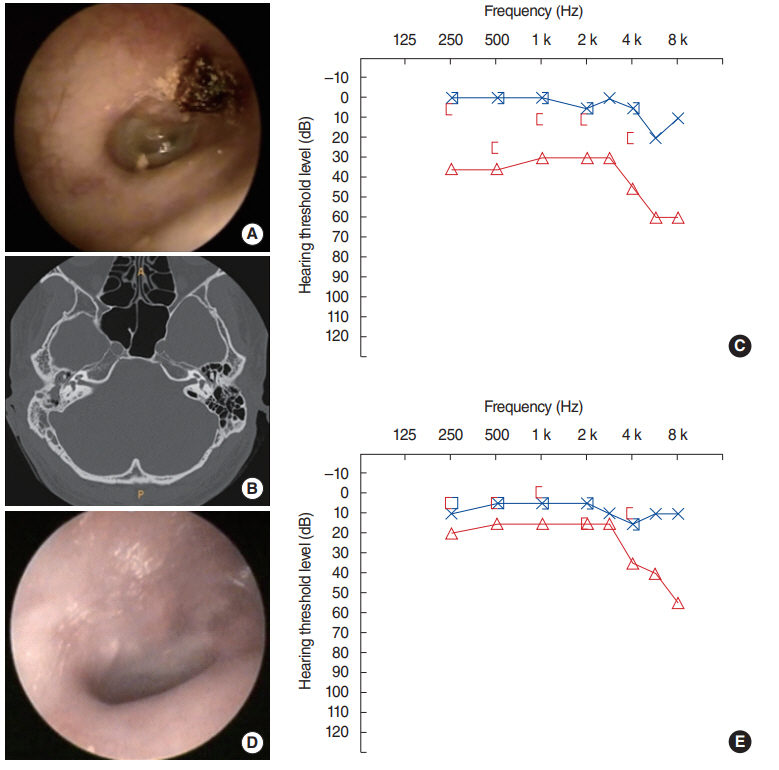

The traditional canal wall down mastoidectomy (CWDM) procedure commonly has potential problems of altering the anatomy and physiology of the middle ear and mastoid. This study evaluated outcomes in patients who underwent modified canal wall down mastoidectomy (mCWDM) and mastoid obliteration using autologous materials.

METHODS

Our study included 76 patients with chronic otitis media, cholesteatoma, and adhesive otitis who underwent mCWDM and mastoid obliteration using autologous materials between 2010 and 2015. Postoperative hearing air-bone gap and complications were evaluated.

RESULTS

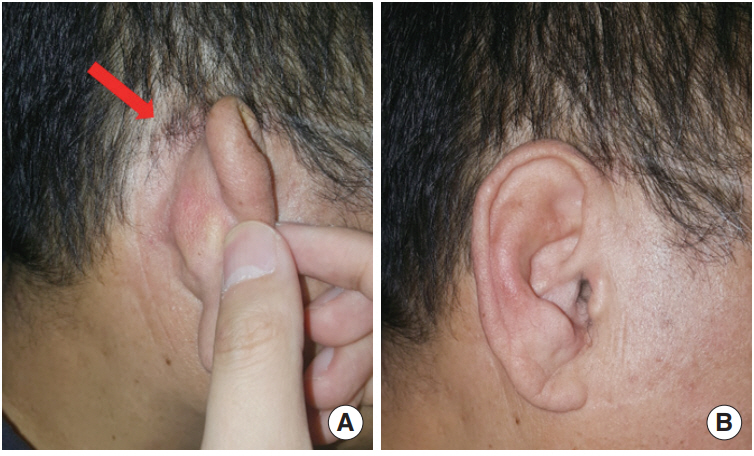

During the average follow-up of 64 months (range, 20 to 89 months), there was no recurrent or residual cholesteatoma or chronic otitis media. No patient had a cavity problem and anatomic integrity of the posterior canal wall was obtained. There was a significant improvement in hearing with respect to the postoperative air-bone gap (P<0.05). A retroauricular skin depression was a common complication of this technique.

CONCLUSION

The present study suggests that our technique can prevent various complications of the classical CWDM technique using autologous tissues for mastoid cavity obliteration. It is also an appropriate method to obtain adequate volume for safe obliteration.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Modified Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy Without Meatoplasty

You Young An, Jong Dae Lee

Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;64(12):965-970. doi: 10.3342/kjorl-hns.2021.00850.

Reference

-

1. Karmarkar S, Bhatia S, Saleh E, DeDonato G, Taibah A, Russo A, et al. Cholesteatoma surgery: the individualized technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995; Aug. 104(8):591–5.

Article2. Charachon R, Gratacap B, Tixier C. Closed versus obliteration technique in cholesteatoma surgery. Am J Otol. 1988; Jul. 9(4):286–92.3. Brown JS. A ten year statistical follow-up of 1142 consecutive cases of cholesteatoma: the closed vs. the open technique. Laryngoscope. 1982; Apr. 92(4):390–6.4. Palmgren O. Long-term results of open cavity and tympanomastoid surgery of the chronic ear. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979; 88(5-6):343–9.

Article5. Sade J, Weinberg J, Berco E, Brown M, Halevy A. The marsupialized (radical) mastoid. J Laryngol Otol. 1982; Oct. 96(10):869–75.6. Smyth GD. Canal wall for cholesteatoma: up or down? Long-term results. Am J Otol. 1985; Jan. 6(1):1–2.7. Palva T, Virtanen H. Ear surgery and mastoid air cell system. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981; Feb. 107(2):71–3.

Article8. Lopez Villarejo P, Cantillo Banos E, Ramos J. The antrum exclusion technique in cholesteatoma surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1992; Feb. 106(2):120–3.9. Yanagihara N, Gyo K, Sasaki Y, Hinohira Y. Prevention of recurrence of cholesteatoma in intact canal wall tympanoplasty. Am J Otol. 1993; Nov. 14(6):590–4.10. Palva T. Operative technique in mastoid obliteration. Acta Otolaryngol. 1973; Apr. 75(4):289–90.11. Gantz BJ, Wilkinson EP, Hansen MR. Canal wall reconstruction tympanomastoidectomy with mastoid obliteration. Laryngoscope. 2005; Oct. 115(10):1734–40.

Article12. Lee WS, Choi JY, Song MH, Son EJ, Jung SH, Kim SH. Mastoid and epitympanic obliteration in canal wall up mastoidectomy for prevention of retraction pocket. Otol Neurotol. 2005; Nov. 26(6):1107–11.

Article13. Black B. Mastoidectomy elimination: obliterate, reconstruct, or ablate. Am J Otol. 1998; Sep. 19(5):551–7.14. Dornhoffer JL. Surgical modification of the difficult mastoid cavity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; Mar. 120(3):361–7.

Article15. Roche P, Coolahan I, Glynn F, Mc Conn WR. Autologous bone pate in middle ear and mastoid reconstruction. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2011; 132(4-5):193–6.16. Grote JJ. Results of cavity reconstruction with hydroxyapatite implants after 15 years. Am J Otol. 1998; Sep. 19(5):565–8.17. Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the evaluation of results of treatment of conductive hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; Sep. 113(3):186–7.18. Moffat DA, Gray RF, Irving RM. Mastoid obliteration using bone pate. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994; Apr. 19(2):149–57.19. Roberson JB Jr, Mason TP, Stidham KR. Mastoid obliteration: autogenous cranial bone pAte reconstruction. Otol Neurotol. 2003; Mar. 24(2):132–40.20. Lee WS, Kim SH, Lee WS, Kim SH, Moon IS, Byeon HK. Canal wall reconstruction and mastoid obliteration in canal wall down tympanomastoidectomized patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009; Sep. 129(9):955–61.

Article21. Wiet RJ, Harvey SA, Pyle MG. Canal wall reconstruction: a newer implantation technique. Laryngoscope. 1993; Jun. 103(6):594–9.22. Ikeda M, Yoshida S, Ikui A, Shigihara S. Canal wall down tympanoplasty with canal reconstruction for middle-ear cholesteatoma: post-operative hearing, cholesteatoma recurrence, and status of re-aeration of reconstructed middle-ear cavity. J Laryngol Otol. 2003; Apr. 117(4):249–55.

Article23. Linthicum FH Jr. The fate of mastoid obliteration tissue: a histopathological study. Laryngoscope. 2002; Oct. 112(10):1777–81.

Article24. Minatogawa T, Machizuka H, Kumoi T. Evaluation of mastoid obliteration surgery. Am J Otol. 1995; Jan. 16(1):99–103.25. Ridenour JS, Poe DS, Roberson DW. Complications with hydroxyapatite cement in mastoid cavity obliteration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008; Nov. 139(5):641–5.

Article26. Cody DT, McDonald TJ. Mastoidectomy for acquired cholesteatoma: follow-up to 20 years. Laryngoscope. 1984; Aug. 94(8):1027–30.27. Austin DF. Staging in cholesteatoma surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1989; Feb. 103(2):143–8.

Article28. Aarts MC, Rovers MM, van der Veen EL, Schilder AG, van der Heijden GJ, Grolman W. The diagnostic value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in detecting a residual cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; Jul. 143(1):12–6.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Modified Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy Without Meatoplasty

- Partial Mastoid Obliteration Using Inferior Based Musculoperiosteal Flap and Autogenous Conchal Cartilage Chips

- Mastoid Obliteration with Silicone Blocks after Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy

- Reconstruction of the Posterior Canal Wall with Mastoid Obliteration after Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy

- A Case of Repair of Retroauricular Skin Defect and Mastoid Cavity with Posterior Wall Reconstruction Using Tutoplast(R)(Allograft Cancellous Bone Chip) and Bone Dust after Canal Wall Down Mastoidectomy