Perspect Nurs Sci.

2018 Oct;15(2):49-69. 10.16952/pns.2018.15.2.49.

Service Quality beyond Access: A Multilevel Analysis of Neonatal, Infant, and Under-Five Child Mortality Using the Indian Demographic and Health Survey 2015~2016

- Affiliations

-

- 1Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

- 2Research Associate, Seoul National University College of Medicine, JW LEE Center for Global Medicine of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Professor, Population Health and Geography, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- 4Professor, International Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Department of Medicine, JW LEE Center for Global Medicine of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. oh328@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2424090

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.16952/pns.2018.15.2.49

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to derive contextual indicators of medical provider quality and assess their relative importance along with the individual utilization of antenatal care (ANC) and institutional births with a skilled birth attendant (SBA) in India using a multilevel framework.

METHODS

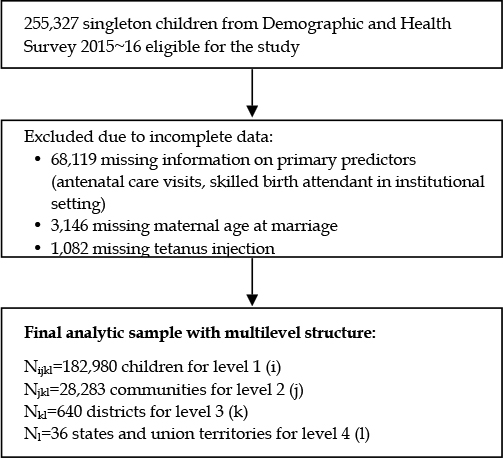

The 2015~2016 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) from India was used to assess the outcomes of neonatal, infant, and under-five child mortality. The final analytic sample included 182,980 children across 28,283 communities, 640 districts, and 36 states and union territories. The contextual indicators of medical provider quality for districts and states were derived from the individual-level number of ANC visits ( < 4 or≥4) and institutional delivery with SBA. A series of random effects logistic regression models were estimated with a stepwise addition of predictor variables.

RESULTS

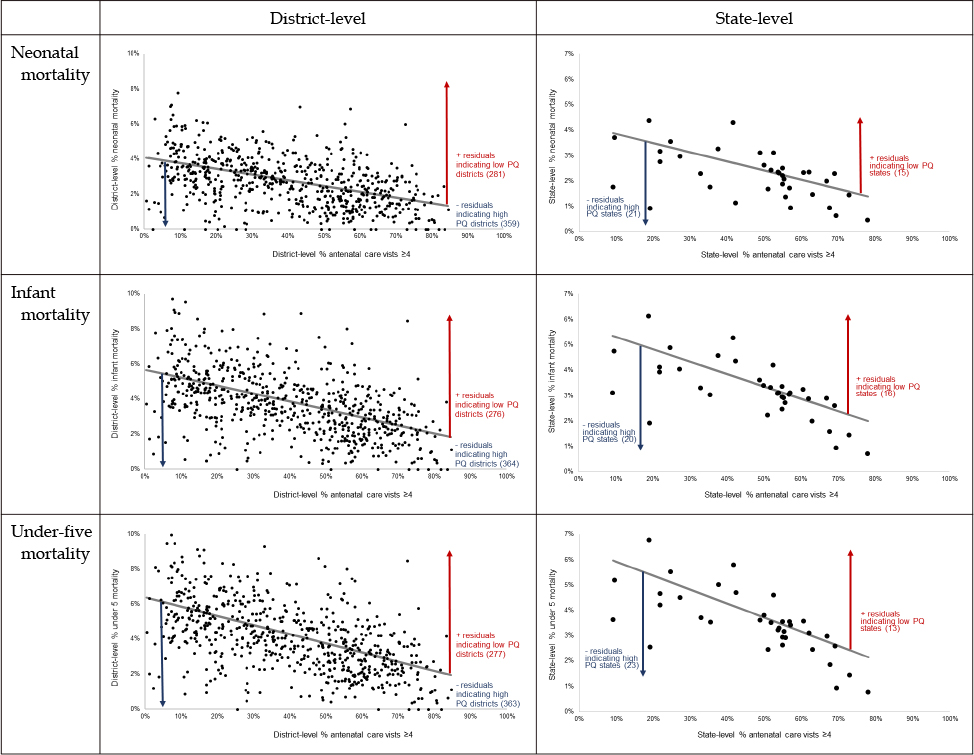

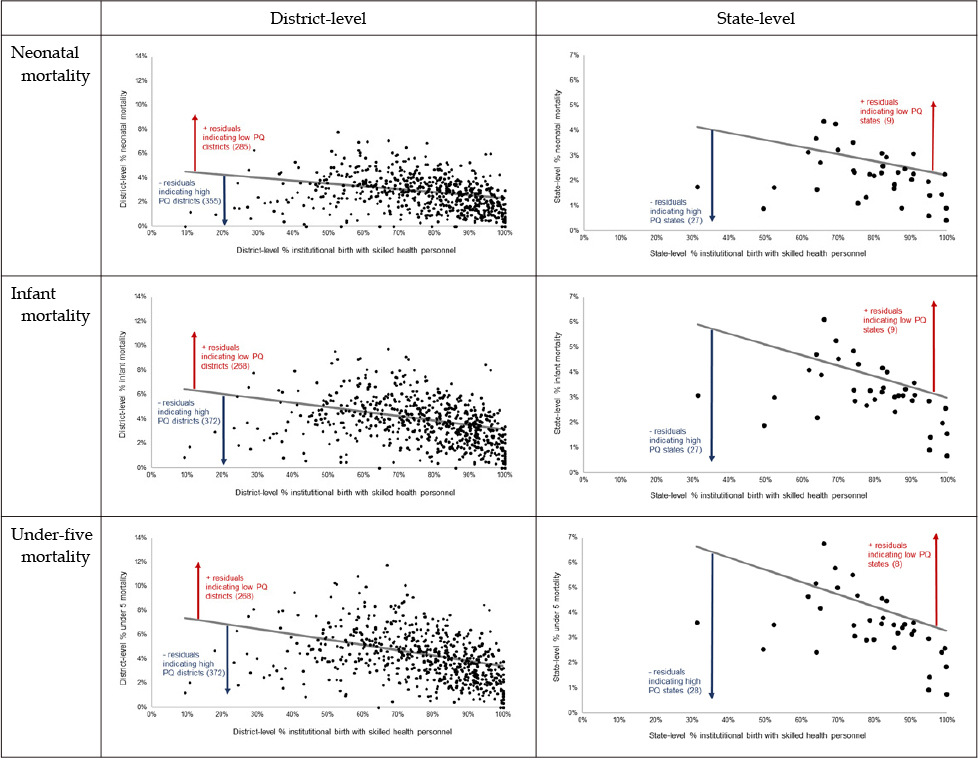

About half of the mothers (47.3%) had attended≥4 ANC visits and 75.8% delivered in institutional settings with SBAs. Based on ANC visits, 276~281 districts (43.1~43.9%) and 13~16 states (36.5~44.4%) were classified as "low" quality areas, whereas 268~285 districts (41.9~44.5%) and 8~9 states (22.2~25.0%) were classified as "low" quality areas based on institutional delivery with SBAs. Conditional on a comprehensive set of covariates, the individual use of both ANC and SBA were significantly associated with all mortality outcomes (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.26, and OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.19, respectively, for under-five child mortality) and remained robust even after adjusting for contextual indicators of medical provider quality. Districts and states with low quality were associated with 57~61% and 27~43% higher odds of under-five child mortality, respectively.

CONCLUSION

When simultaneously considered, district- and state-level provider quality mattered more than individual access to care for all mortality outcomes in India. Further investigations are needed to assess the importance of improving the quality of health service delivery at higher levels to prevent unnecessary child deaths in developing countries.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. United Nations Children's Fund. Committing to child survival: a promise renewed. New York: United Nations Children's Fund;2015. 09. 96. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/APR_2015_9_Sep_15.pdf.2. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). ‘Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2017, Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation’. New York: United Nations Children's Fund;2017. 10. 36. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Child_Mortality_Report_2017.pdf.3. Dutta AK, Aggarwal A. Newer development in immunization practices. Indian J Pediatr. 2018; 01. 85(1):44–46. DOI: 10.1007/s12098-017-2530-y.

Article4. National Health Mission, Government of India. About NHM [Internet]. [place unknown]: National Health Mission, Government of India;c2014. cited 2018 Jun 15. Available from: http://nhm.gov.in/nhm/about-nhm.html.5. Sidney K, Diwan V, El-Khatib Z, de Costa A. India's JSY cash transfer program for maternal health: Who participates and who doesn't-a report from Ujjain district. Reprod Health. 2012; 01. 24. 9:2. DOI: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-2.

Article6. Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010; 06. 375(9730):2009–2023. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1.

Article7. Barros AJ, Victora CG. Measuring coverage in MNCH: determining and interpreting inequalities in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health interventions. PLoS Med. 2013; 10(5):e1001390. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001390.

Article8. Corsi DJ, Subramanian SV. Association between coverage of maternal and child health interventions, and under-5 mortality: a repeated cross-sectional analysis of 35 sub-Saharan African countries. Glob Health Action. 2014; 09. 03. 7:24765. DOI: 10.3402/gha.v7.24765.

Article9. Kruk ME, Freedman LP. Assessing health system performance in developing countries: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 2008; 03. 85(3):263–276. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.09.003.

Article10. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2016. 152. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=85AACE248B0D56E19D87FD68711C370F?sequence=1.11. Lincetto O, Mothebesoane-Anoh S, Gomez P, Munjanja S. Chapter 2, Antenatal care. In : Lawn J, Kerber K, editors. Opportunities for Africa's newborns: practical data, policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa. [Geneva (Switzerland)]: World Health Organization;2006. p. 51–62. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/oanfullreport.pdf.12. Gupta A, Fledderjohann J, Reddy H, Raman VR, Stuckler D, Vellakkal S. Barriers and prospects of India's conditional cash transfer program to promote institutional delivery care: a qualitative analysis of the supply-side perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018; 01. 25. 18:40. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-2849-8.

Article13. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS;2017. 637. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf.14. Okeke EN, Chari AV. Can institutional deliveries reduce newborn mortality? Evidence from Rwanda. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation;2014. 12. 47. Available from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1000/WR1072/RAND_WR1072.pdf.15. Banerjee A, Duflo E. Addressing absence. J Econ Perspect. 2006; 20(1):117–132. Win. DOI: 10.1257/089533006776526139.

Article16. Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K. The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. J Econ Perspect. 2008; 22(2):91–116. Spr. DOI: 10.1257/jep.22.2.93.

Article17. Chaudhury N, Hammer J, Kremer M, Muralidharan K, Rogers FH. Missing in action: teacher and health worker absence in developing countries. J Econ Perspect. 2006; 20(1):91–116. DOI: 10.1257/089533006776526058.

Article18. Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001; 15:Suppl 1. 1–42. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.0150s1001.x.

Article19. Bhutta ZA. Mapping the geography of child mortality: a key step in addressing disparities. Lancet Glob Health. 2016; 12. 4(12):e877–e878. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30264-9.

Article20. Singh A, Pathak PK, Chauhan RK, Pan W. Infant and child mortality in India in the last two decades: a geospatial analysis. PLoS One. 2011; 6(11):e26856. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026856.

Article21. Raven JH, Tolhurst RJ, Tang S, Van Den Broek N. What is quality in maternal and neonatal health care? Midwifery. 2012; 10. 28(5):e676–e683. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.09.003.

Article22. Dettrick Z, Gouda HN, Hodge A, Jimenez-Soto E. Measuring quality of maternal and newborn care in developing countries using demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2016; 06. 11(6):e0157110.

Article23. Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Prasad S, Casey M, McClellan M, Moscovice IS. Birth volume and the quality of obstetric care in rural hospitals. J Rural Health. 2014; 30(4):335–343. Fall. DOI: 10.1111/jrh.12061.

Article24. Pileggi-Castro C, Camelo J Jr, Perdonaá G, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Cecatti JG, Mori R, et al. Development of criteria for identifying neonatal near-miss cases: analysis of two WHO multicountry cross-sectional studies. BJOG. 2014; 03. 121:Suppl 1. 110–118. DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.12637.

Article25. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), ICF. Fact Sheet, National Family Health Survey(NFHS-4), 2015-16. IIPS;2017. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml.26. National Family Health Survey. NFHS-4 [Internet]. Maharashtra: International Institute for Population Sciences;c2009. cited 2018 Jan. Available from: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/nfhs4.shtml.27. Subramanian SV, Glymour MM, Kawachi I. Chapter 15, Identifying causal ecologic effects on health: a methodologic assessment. Macrosocial determinants of population health. New York: Springer;2007. p. 301–331.28. Kim R, Mohanty SK, Subramanian SV. Multilevel geographies of poverty in India. World Dev. 2016; 11. 87:349–359. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.07.001.

Article29. Subramanian SV, Jones K, Duncan C. 4. Multilevel methods for public health research. Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University Press;2003. p. 65–111.30. Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. 4th ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons;2011. p. 382.31. Ejigu Tafere T, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Antenatal care service quality increases the odds of utilizing institutional delivery in Bahir Dar city administration, north western Ethiopia: a prospective follow up study. PLoS One. 2018; 02. 08. 13(2):e0192428. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192428.

Article32. Ram F, Singh A. Is antenatal care effective in improving maternal health in rural Uttar Pradesh? Evidence from a district level household survey. J Biosoc Sci. 2006; 07. 38(4):433–448. DOI: 10.1017/S0021932005026453.

Article33. Bloom SS, Lippeveld T, Wypij D. Does antenatal care make a difference to safe delivery? A study in urban Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Policy Plan. 1999; 03. 14(1):38–48. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/14.1.38.

Article34. Liu L, Li M, Yang L, Ju L, Tan B, Walker N, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: a validation study linking population survey derived coverage to maternal, newborn, and child health care records in rural China. PLoS One. 2013; 05. 07. 8(5):e60762. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060762.

Article35. Stanton CK, Rawlins B, Drake M, Dos Anjos M, Cantor D, Chongo L, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: testing the validity of women's self-report of key maternal and newborn health interventions during the peripartum period in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2013; 05. 07. 8(5):e60694. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060694.

Article36. Suzuki E, Yamamoto E, Takao S, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Clarifying the use of aggregated exposures in multilevel models: self-included vs. self-excluded measures. PLoS One. 2012; 7(12):e51717. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051717.

Article37. Rani M, Bonu S, Harvey S. Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008; 02. 20(1):62–71. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm052.

Article38. Heredia-Pi I, Servan-Mori E, Darney BG, Reyes-Morales H, Lozano R. Measuring the adequacy of antenatal health care: a national cross-sectional study in Mexico. Bull World Health Organ. 2016; 06. 01. 94(6):452–461. DOI: 10.2471/BLT.15.168302.

Article39. Carvajal-Aguirre L, Amouzou A, Mehra V, Ziqi M, Zaka N, Newby H. Gap between contact and content in maternal and newborn care: An analysis of data from 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health. 2017; 12. 7(2):020501. DOI: 10.7189/jogh.07.020501.

Article40. Hodgins S, D'Agostino A. The quality-coverage gap in antenatal care: toward better measurement of effective coverage. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014; 04. 08. 2(2):173–181. DOI: 10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00176.

Article41. Powell-Jackson T, Mazumdar S, Mills A. Financial incentives in health: New evidence from India's Janani Suraksha Yojana. J Health Econ. 2015; 09. 43:154–169. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.07.001.

Article42. Mohanty SK, Kim R, Khan PK, Subramanian SV. Geographic variation in household and catastrophic health spending in India: assessing the relative importance of villages, districts, and states, 2011-2012. Milbank Q. 2018; 03. 96(1):167–206. DOI: 10.1111/1468-0009.12315.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of Maternal Child Health Services in Korea: Perspective of the Premature Infant

- Multilevel Analysis of Factors Affecting Health-Related Quality of Life of the Elderly

- Ecological context of infant mortality in high-focus states of India

- Health-Related Quality of Life in the Early Childhood of Premature Children

- Deprived areas and community water fluoridation in Brazil: a multilevel approach for refocusing public policy